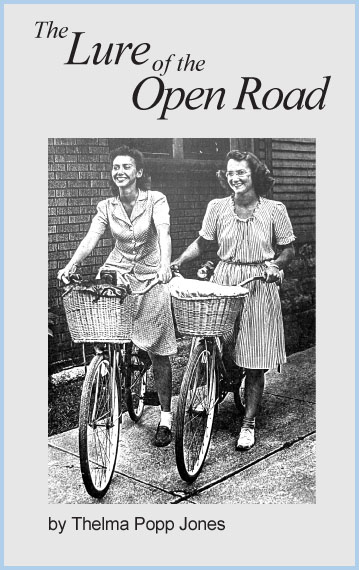

The Lure of the Open Road.

Wartime wandering through the Eastern states by bicycle, truck, and riverboat. 1944.

by Thelma Popp Jones. 2007.

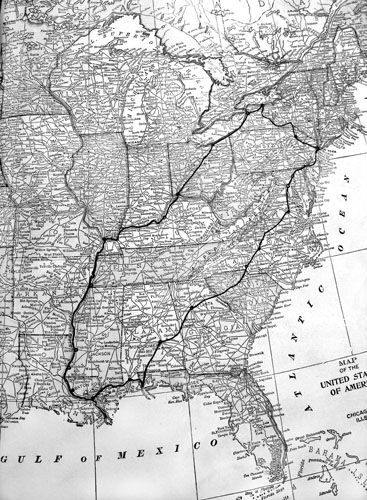

In 1944, a dear friend, Doris Roy, and I undertook an adventurous journey that we dreamed of during countless hikes together over our college holidays. We had been Camp Fire Girls together, loving the out-of-doors, camping and hiking the open road. Our dreams finally developed into a plan to ride bicycles from our home in Buffalo, New York, to Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River met the Mississippi. We admired Mark Twain’s adventures, had read his Life on the Mississippi, and sought to follow his path to the Midwest.

We were 21 years old, just graduated from college: Doris Roy from Michigan State and Thelma Popp from Buffalo State College. We often referred to each other as "Mouse," as we were two blind mice wearing glasses. I had the nickname "Poppy," characteristic of my last name.

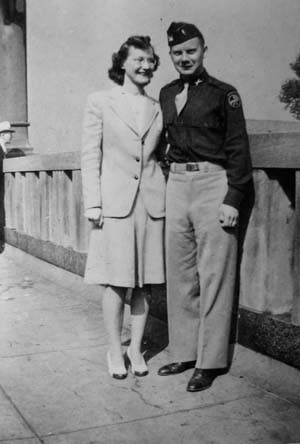

World War II affected our college life as most of the male student body joined one of the services. Women assumed some of their roles by taking jobs in armament industries. During the summer, I worked from early morning to evening in a public school caring for infants whose mothers were working in aircraft factories or other related industries.

But now, before starting our careers, we decided that the coming summer after graduation would be the ideal time to have our adventure. We had a limited period of time to accomplish this. I had signed a contract to begin teaching first grade in Middleport, New York, on the Erie Canal on September 4, 1944. And so - with the leanest of equipment - we made our preparations and were ready to leave on June 22, 1944.

Part 1

June 22 - July 21, 1944

Leaving

Buffalo

June 22, 1944

This was the day, the first day of our adventure by bicycle. It was the reality of a dream one day toward completion. It was the beginning of an adventure, months of hoboing through the country to live as we pleased and go where we willed. And now, at 7:30 a.m., the Roy family arrived at the Popp residence at 134 Oakgrove Avenue, Buffalo, New York, to share breakfast together with their children, Doris and Thelma. Perhaps in the future we would be looking back at the wealth and the pleasure of that breakfast and the kind words of our parents still attempting to discourage us. Perhaps it was a ridiculous venture, but we were determined never to be put into the category with those who say, "I always wanted to, but never did." Out on the driveway were standing two beautiful new bicycles. Both were blue and their chrome fittings shone like silver in the sun. A previous checkup reported all parts oiled and geared for efficiency. These were our wartime Victory bicycles, lightweight and practical. Thelma’s bicycle had but one speed, and Doris’s had two. But an ordinary bicycle never looked like this! Every extremity was used as a carrier. The usual rack over the rear wheel was extended to hold the weight of a sleeping bag and duffle, and below, saddle bags bulged on either side of the wheels. Strapped to the handlebars was a wicker basket outfitted with oil cloth for protection against inclement weather. These were our bicycles - carnivals on wheels! We were all keyed up to this exciting moment.

"Where was this packed? Can I leave out those rubbers Mother said to take?"

"Which would you rather carry, the hatchet or the kettle?"

"Did I remember the pot scraper?"

"And now what bag did I put the canned heat in?"

"Do we need my compass? Wish we had a bike speedometer."

"Remind me not to tip the bike on that side, Mouse. I put the camera in there."

Leaving Buffalo. (22 June 1944)

Mr. Popp started focusing the movie camera. I snapped closed the cover on my basket for the last time. Farewell kisses....

"Keep dry! Wear your hats!"

Mr. Popp clicked the lever of the camera and aimed at us through the lens. We pedaled down the drive, into the street, and out into the world. Down over the rough brick pavement, up the viaduct and over the freight yards we pumped and sweated. The outskirts of the city were an endless line of mills and factories belching smoke and soot. The odor of the chemicals stung our nostrils and dried our throats. We were glad to leave the city.

We must have been a humorous sight - bicycles bulging at all angles, tin cans jangling as we hit the bricks, and riders vainly attempting to keep their floppy hats from being carried off in the wind.

I had packed my bicycle the preceding night and only took a turn around the drive to determine how I could navigate with a heavy load. Now things seemed different. I couldn’t be tired already. We’d only gone two miles!

The low grades of the highway assumed great heights. I pressed hard on the pedal and could see the muscles in my knee tense and relax. My heart pounded as we reached the top. Then, easing off on the pedal, down the other side we flew with a rush of cool air hitting our hot faces.

Our route had been mapped toward Pittsburgh. Could we have chosen more mountainous country? Undaunted, we rolled out of the city south to the Appalachians. The highway was broad now. Factories, trolley cars and houses were left behind. Before us lay the world, the world of waving grasses, scorching sun, hills for a bed and two months of an unfettered vagabondish life. We were to be the transient neighbors of all who lived by the side of the road.

There was only one thing against us - the wind that blew from Lake Erie. Only a few miles along the lake to Fredonia and we would change directions. Things would ease up then.

Doris was saying, "Let’s stop for a sip from our canteens and rest a little. We don’t want to overdo it the first day."

The ice cold water we had poured into our canteens was now lukewarm. We lay with our backs to the ground. The wind that had restrained us on the highway felt cool as it rippled over us. After that little refreshment, we once again bent against the wind, following the sun through the sky. With the road as our guide and the sun as our timepiece, we chose the hour of eating and rest as we willed.

Now the sun was setting; this was to be our first night. We drew up beside a narrow dirt road that wound back into the hills. We were about six miles from Silver Creek, New York.

"What do you think, Mouse? Shall we try our luck for a camping spot down this road?" The friendly little dirt road turned out to be a deserted one. From rut to rut we bounced, continually climbing to lonelier territory. Our camper’s handbook had always described a good campsite as one being on smooth, level ground, beneath shady trees and by a babbling brook, but our visions of a Shangri La faded and we began searching for a fairly private and level piece of land. "Hello, neighbors!"

A very active, tail-thumping mongrel had jumped out into the road and dashed madly between us and a small gray house set back in the trees. Several people were on the front porch, and one small girl came down the stairs and along the driveway. She welcomed us with a broad smile. Her mother and father then came down and greeted us. "Hello, girls. Are you on a camping trip?"

Who would ask permission? Would they receive us? So much depended on our first night. Then Doris explained our mission.

"We’re on a camping trip. We just started from Buffalo this morning. It’s been quite a pull against the strong wind and we’re rather tired, so we decided to look for a suitable camping spot for the night and give our legs a rest."

"Jim," the woman turned to her husband, "why couldn’t the girls go down by the creek?" The father rubbed his chin. "That would be all right, but there are a lot of mosquitoes down there. Why not over on the bank beyond the west field? That’s about the most level spot around here."

Before we knew it we were being escorted through the west field, and then we were on the bank. Who said no Shangri La? This was it!

We were in a small clearing bounded by trees. On one side was a wooded cliff, and below it was a shallow stream and a picturesque waterfall.

Home! Out came the tin cans. Out came the cooking kits. The bedrolls were untied. The provisions for dinner were placed on a level rock. We scoured through the trees, cracking wood and dragging back dead limbs and twigs.

"This shouldn’t be hard at all," Doris said as she knelt on a cleared spot and began shaping the twigs in tepee fashion. I began cutting the potatoes into smaller pieces, washed the lettuce in an inch of water in the canteen cup and laid out the veal chops.

"There it is!" She began blowing gently on the yellow spiral of the flame. Then - the sizzling of the chops in butter, the bubbling of the water about the potatoes, the lettuce dividing - we sat back on the grass balancing our cooking kits and canteen covers. It was the first real cooked-out meal, and a well earned one.

With the dishes washed and the prunes put in to soak for breakfast, we were off with our soap and towels to the creek below. We bounded down the side of the bank and ran out for a quick swim and a splash in the waterfall. Joyous laughter and singing floated along with the soapy suds and the current. We washed clothes and draped them over the branches of trees.

Up again on the bank, we pounded through the brush, walking up and down small inclines searching for two pieces of level land for sleeping. At last we settled for a small clearing with the fewest roots and the least amount of stones and bumps. We sat on our bedrolls, creaming our faces, brushing our hair and violently slapping mosquitoes. Post cards to our parents were dashed off, and we wrote the following account in our logs:

June 22

miles - 32

8:30 Buffalo

12:00 Lake View (lunch)

5:30 Six miles from Silver Creek

Milk $0.15

Veal Chops $0.25

Prunes $0.16

Potatoes - free

4 eggs $0.23

6 slices of bacon

Lettuce $0.15

2 birch beers $0.10

Total $1.04 (Poppy pays first two days)

The moon was out, and in its light I could see a horde of mosquitoes walking up and down the netting in dizzy design, testing the size of each hole. One found a sizable opening to venture through where I had ruffled the cover. Others followed and then began the bombardment that sent me diving head and all into the sleeping bag. I could hear their droning and imagined the battle that might ensue if I let as much as my nose protrude.

A warm wind started up, and the rain flap over my head lapped to and from as the supporting sticks swayed. A quick look out disclosed a hazy moon and a reddened sky. I had just settled down, convinced that I must reconcile myself with these pesky creatures, when I heard a low growl behind me. I feared to moved a muscle or reveal I was alive. Visions of a watchdog grabbing off a leg, then the sound of scampering off through the underbrush. It was gone. For one brief moment I had forgotten the mosquitoes.

Was night always encountered this way? Was I really going through this every night for a whole summer? For one passing moment I doubted the success of our trip.

* * *

June 23, 1944.

The sun had swung far into the sky before we began to stir and stretch in our bedrolls. I gradually became conscious of the brilliant sunlight and was able to discern bushes and trees that had been the vague shapes and shadowy substances of the night before.

"Morning, Mouse," I called over to Doris. We inched ourselves up into sitting positions and observed the outside world, wet and sparkling with a heavy dew. "Up then, my comrade, and have a look at our soaking prunes!" Other than a few drowned ants mixed in they were ready for cooking.

Taking the dewy mat of grasses from our woodpile, we found our supply of wood dry and ready for use. It was no time at all before the firewood was crackling and snapping. The prunes were soon boiling, the scrambled eggs were simmering in the frying pan, and the bacon was curled and sputtering. Hunched on our knees to avoid the damp grasses, we sang the morning blessing and divided the stewed prunes. "How about sharing the salt mix?" Doris asked as she whittled at the bacon in the frying pan with her jackknife. Her plate was the pan, mine the cover. I tossed over to her the little glass tube that contained salt and pepper. The eggs were a little hard, but the tea helped out.

"More tea, Mouse?" I inquired. The cups that clamped onto the canteens each held a pint. I filled the cup up to the nails that held the handle. That was our measure for an equal portion.

With breakfast over, we slid down the muddy bank to the creek bottom and knelt in the water to scour the blackened pots. The #10 tin can with its wire baling handle was the blackest. We had used it for the dishwater, and it had sat in the coals to boil while we ate. We took turns breaking our nails over it.

Little sprinkles of white cleanser blew to the surface of the stream and followed the pattern of its swirl over the pebbles. Suddenly, a drop of water splashed into the pool, sending wavelets inundating to the beach. Others followed, prickling and bubbling the water. Quickly we grabbed up our kettles and made for the campsite. Our beds had to be rolled and the equipment stored away before everything was soaked. Down came the stakes. Down came the washing. Down came the rain.

"God bless the rubbers," Doris said, as I tied my oilskin kerchief over my head. "Better cover up that box of Mother Weed’s Noodle Soup. That and the canned heat might come in handy today."

The rain was falling softly now as we made one last checkup on the camping grounds. Upward and onward we cautiously rolled over the road, avoiding the unknown depths of the swimming ruts. Our wheels sped down the steep incline as the road brought us back to the main highway. Our raincoats flew out in back of us and our pigtails were whisked up into the air.

Rain or no rain it was a good beginning. We were well fed. We were happy. Along the shining road to Silver Creek we sped, the sound of the wheels’ song stinging the wet pavement.

The town was just creeping out of its slumber as we made for our objective on the village square - the Post Office. The tale of our first day had been written in our journals, and our first letter home.

We leaned our bicycles against the rail and scrambled up the steps. Before I had my hand on the latch the door swung open in my face. A ruddy-faced gentleman tipped his hat and held the door open. I murmured a greeting in return and stepped inside the doorway. After depositing our letters, we found the same gentleman flicking a match over the railing and glancing at the queerly loaded bicycles.

"Are you going somewhere or coming?" he questioned.

Unwilling to share the extent of our dream, we explained we were headed for Fredonia. After introducing ourselves, we found him to be a pastor in the town. Challenged by curiosity, he had to know the details of our plans, so we told him of our proposed route to Pittsburgh and Virginia, then directly west to the Mississippi River. We laid out our maps and studied the route.

"The hills?" he questioned. "How good are you at climbing hills? You’ll strike the mountains in Pennsylvania, and remember, there’s an up to every down." The first day of bicycling had proved the difficulty of pedalling up even a small grade with such a load, yet we would like to go south and touch Virginia. We mused and measured. Ohio seemed a dull state, but it was true - it was more level and the distance shorter. So, we decided to be sensible, follow his advice, and cross Ohio. In the afternoon we found ourselves in Chautauqua County, in one of the largest and most beautiful grape belts in America. The day was such a lovely one, the Maxfield Parrish type with lots of blue. A lazy wind puffed the clouds along above the sloped vineyards. The sky was blue and the was road level. Vineyards stretched their way over the slopes at our left, and at our right they marched in straight columns to the blue lake.

When we returned, that pattern would be interrupted by bobbing straw hats and a motley group of skirts upon a field of blue. Harvest time and yellow baskets brimming with grapes. We took advantage of that dream and stopped at a farmhouse for a cold glass of last year’s vintage.

All people, all signs interested us. We had time for everything, so when we read the sign "Antiques," we decided to investigate. It was a well-weathered sign, swinging there as its scrolled standard. Signs that are finely printed and hanging before the well-polished house do not interest me, but this one I found inviting.

The house played its part well, from the slate walk up to the crumbled brick wall. The jangle of the doorbell brought forth a very courteous connoisseur of antiques. The musty smell and thickness of dust were delightful. It meant old things with history behind them, perhaps some colorful stories, too.

Doris strayed off to another room and left me scrutinizing the cut glass, the fine China and an array of silver. Displayed on rows of dusty shelves and tables were the fruits of an endless search of the collector for the original and the unique. Here was a flowery Dresden figure with a dainty foot showing beneath her lace dress. And a red-lipped lover hovered over her under a bower of glazed roses.

I surveyed a low-hanging shelf lined with small pitchers. There was some copper lustre ware still boasting a metallic glow under the dust. Here was a Stevenson platter: a dark blue American scene painted in the bottom and bordered by the customary oak leaf and acorn.

Many of the antiques were collected throughout the historical era of New York State, the days of DeWitt Clinton and his canal, the Pan-American Exposition of 1902, President McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt.

Suddenly, beyond the rose-colored vases, beyond the paned windows, I saw the trees

bend and the wind sweep through the streets. It had become darker and we had yet to

find a camping spot for the night. I unearthed Doris from the grandfather clocks and

ladder-back chairs, thanked the shopkeeper for her kindness, and we rushed out to

get our bikes.

Swiftly biking along, we entered Westfield, a quaint small town with a broad shady street. The houses were spacious, comfortable and inviting. We stopped at a small grocery store to buy provisions. While busily deciding the cheapest and best brand of cereals and looking over the grapefruit and carrots, we overheard two customers who were leaning over the counter.

"The radio says it’s acomin’ right across Penn, taking down houses and trees, and people gittin’ hurt, too!"

"Where’s it ever goin’ to, Mrs. Johnson?"

"I don’t know. Probably we’ll get a little of it over here ourselves."

"Think I’ll go right home and close up the windows. Might just as well take precautions."

Indeed, the sky was getting darker and darker. We quickly paid for our purchases and set off. Turning north at the signal, we headed for the lake, but a short distance from the town we came to a stop at a farmhouse. It met our specifications exactly - a huge red barn with a prosperous hayloft and a pump next to the house.

A kind farm lady answered our knock. It was my turn to do the inquiring so I explained. "We’re on a camping trip, biking through the countryside. It looks like we’re in for a rainstorm tonight, and we wondered if we might sleep in your hayloft."

"It seems to me that a hayloft would be a mighty uncomfortable place to sleep in," she said. "I’m sorry I can’t offer you a bed in the house here, but my daughter is visiting with her baby. Just a minute. I’ll call John."

The barn door rolled back and John emerged carrying a basket of freshly laid eggs. "Certainly," was his answer. "As long as you don’t use matches the barn is yours for the night."

We rolled the barn door back farther to light the interior. What a spacious guest room! A wheelbarrow to lay out our breakfast, bars to hang our laundry, and a well-padded hayloft for us alone!

Doris swung up the ladder and I tossed the bedrolls up to her. Then we pounced around on the hay and stacked it into springy beds. The storm seemed far enough away. Surely there would be time enough to eat dinner, maybe even to take a swim. We rolled out our bikes again and went down the road and through a field until we came to a barren spot on the cliff. The stone went straight down to the jagged rocks below. The waves splashed up and broke into white foam.

Now the drops of rain were beginning to fall, but we gathered sticks for the fire and cut up the potatoes and carrots. Eventually the fire blazed and the water boiled feebly. We ate in our bathing suits with one eye on the southeastern sky and the other on the flame beneath the dishwater. At last we were all through and ready to go down into the water for a quick dip.

Taking our soap and towels, we cautiously climbed down the shale embankment, hooking our feet in the ridges where the shale had broken. We threw off our bathing suits and proceeded to the middle of the stream, ankle deep in warm water. Our songs vibrated through the ravine as we lathered and splashed.

Lake Erie looked formidable along the horizon. A stout wind pushed the black clouds across the sky until the blue was dissolved into low-hanging balls of darkness. Approaching us from across the lake came a veil of rain. It came as a curtain, leaving a churning wake behind it and breaking up the calm reflection before it. There was a sudden blast of thunder. The wind began to weep and wail, and a torrent of rain flung itself on us in a beating needle shower. The clouds were losing their reserves, the blackness was gone, but an eerie white light illuminated the sky, casting all earthly things in a dark shadow. The banks were hardly visible, except for a few trees curved with the wind, their branches sweeping to the ground. I struggled into my bathing suit and snatched after my case of soap as the wind blew it away. Turning to climb the foothold we had used in descent, I found a tumultuous waterfall of brown mud sweeping over the cliff. The current of the stream was forced to reverse itself as volumes of water tumbled in torrents through the narrow neck from the lake.

We were caught! We yelled back and forth to one another over the pounding storm. "What can we do? Are you all right?"

"Mouse, what’s happening to our bikes? Our bikes! Our bikes! I said, our bikes, our bikes! Will they be swept over the cliff?"

"What? It’s a cyclone! We’ve got to get up! Come on over here."

Doris motioned me over and we started digging our hands and feet into the mud wall gradually gaining height. Then, goaded with that spurt of energy that comes with fright, we scaled the embankment.

Our equipment was strewn all over. The corn flakes were sprinkled all about. A grapefruit had rolled several yards away. The carrots lay near the cooking kits and our water-filled rubbers. We righted the capsized bicycles and began to put things away helter skelter. Everything was soaked. Then Doris stood up and flourished her arm above her head.

"Here it is... the only thing that’s dry! Can you beat that?" She was holding aloft the precious package of Mother Weed’s Noodle Soup!

The corn field was a river of mud, a thick creamy mass rushing to spill over the cliff. With the path completely lost, we waded up to our knees in the mud in the general direction of the road. Mud worked under the fenders of the bikes and covered the tires; silt oozed between our toes. Never were the paved road and green lawn so welcome.

The cyclone had done its damage, leaving behind its victorious rainbow. We spent the rest of the afternoon scrubbing and polishing our bicycles under the pump.

And so, into a good dry hayloft to sleep. This was the second day. Somehow it seemed that our perseverance was being tested. One consolation: tonight there would be no mosquitoes!

Biking

New York, Pennsylvania to Ohio and Kentucky

June 24, 1944

Agenda for June 24

Morning - Parson's Farm

Noon - Held up by wind and rain

Night - Johnny Phillips' Farm, Pennsylvania

Breakfast - Grapefruit, bran flakes, dried prunes, milk

Dinner - (Restaurant) Mushroom soup, ham sandwich, milk (2 glasses)

Breakfast milk $0.05

Grape juice $0.20

Soup $0.20

Sandwiches $0.40

Milk $0.40

2 eggs (found lying in chicken coop) $0.00

Total $1.25 (Doris Pays)

It was the scratching and cackling of the chickens that woke us up. The room opposite us was alive with noises. The rooster crowed and from within came the whirring and flapping of wings of a hundred chickens. The barn was still dark and the rain was beating on the roof.

Daylight soon came and with it the feeble rays of sunlight. I watched the little flocks of dust revolve around the beam of sunshine that streamed through the broken pane. The slightest movement of the hay and puffs of dust danced up the beam, spun around, and came to rest again. We did not emerge from our bed rolls until late in the morning, and then lazily put on our slacks and sweat shirts.

After breakfast we went over to the farmhouse. They very hospitably let us dry our shoes and towels on the parlor heater. There, lying on the table, was our old favorite Larry. We used to read it by firelight at camp. Curled up in a big leather chair by the coal stove, with feet tucked under me and the familiar Larry in my lap, I wondered at the safety and security of two Mice along the road. After the excitement we had passed through the night before, here lay comfort and friends. Dried and packed we started on the road once again. Today we would put on miles and reach the state line. It was now 3:00 p.m. and we sped along the highway toward the Pennsylvania border. In the late afternoon we had biked eighteen miles to the northeast county of Pennsylvania.

Reaching Pennsylvania State Line. (24 June 1944)

Barns, we decided through two nights’ experiences, were the best places to roll out our sleeping bags. Consequently, at sundown we rolled up to a red brick farmhouse and asked permission. This time it was granted by a young man, Johnny Phillips. Our mattress for this night was to be alfalfa, freshly mown and sweet-smelling. I climbed into the tractor parked at the barn door, intending to write the day’s journey in my log, when Johnny came whistling down the path. He stopped to pull off a cluster of cherries and tossed some to us.

"That’s a good looking outfit you have to carry you along," he said, swinging atop one of the tractor’s hard rubber wheels. "Where did you get the idea of going on such a trip?"

Johnny was a Penn State graduate, an Alpha Zeta, and he was a typical college boy - well built, ruddy faced, and bursting with pride for his Alma Mater and his fraternity. We all sat on the tractor dangling our feet over the sides and chewing on hay. Johnny was explaining about college.

"You see, this farm is 850 acres, so I decided if I was ever going to run it, I would have to go to an agricultural school. So, that’s what I did. The state paid most of my tuition and that helped cut down on the expenses. You see, this is mainly a fruit farm - fruit, trees and vineyards. That means you have to know a lot about insecticides and farm equipment."

"Yes," Doris said, "I know what you mean. I went to a state college myself, and they have an excellent ag. department. That’s one thing we’re learning on this trip. People have been so wonderful to us. They open their barns to us and want us to stay in their homes. They give us milk, dry out our wet clothes and give us parental advice for our trip. The people of the United States are pretty fine. We’re finding that out."

We had drifted from one conversation to another when I glanced around and said, "Look how dark it’s getting. We’d better be hitting the hay."

"You don’t mean this early," Johnny said. "It’s Saturday night and I’m going into town. How about letting me show you around? Let’s go to a movie."

"Thanks a lot, Johnny, but Poppy is right. We’ve got to start early tomorrow and that means a good night’s sleep. How about doing up the town for us, too?"

Johnny swung into the car and rolled down the drive. We jumped from the tractor and began to fix our beds in the alfalfa. Suddenly, a little old man appeared. He had gray hair, a wrinkled face and watery blue eyes. "Well now, what have we got here?" he asked.

We explained our presence.

"What?" he asked. "Girls sleeping in a barn? Well I declare. Now aren’t you afraid to sleep in a barn? You’re not? Well glory be! I tell ye what you do. You foller me... come on now... foller me right down these stairs."

We followed the little man named George down the steps, past the rows of cows and into the milk room. He began to fill large cups with rich creamy milk.

"This is just what you need to put some red into your cheeks. Make you feel peppy." And we did feel good. We felt like robust examples of perfect health. We thanked our friend and said goodnight. Then we climbed into the loft.

"Well, Mouse, this is Pennsylvania. Tomorrow we’ll be in Erie."

Doris put the last pin into the last curl. "Yep, and tomorrow’s Sunday. Well, I’m for some shuteye. Night, Mouse. Happy dreams."

I turned over and thought about all the things that had happened. If all that happened in three days, what would the rest of the summer be like?

* * *

June 25, 1944

The next morning the rays of sunshine filtered through the dusty cracked windows. A small black and white kitten had curled up on Doris’s chest and went up and down in regular time to her breathing. Another stretched its warm body across my feet.

"Morning Mouse," came from the bedroll near me. "Today’s Sunday, and isn’t it a beautiful day?" She freed an arm, stretched out from the hole and unzipped herself. We gathered up our tooth brushes and towels and hiked downstairs, past the sleeping cows and into the milk room. Breakfast on this morning was quite domestic. One of the hired men let us poach our eggs on his gas range and, for the first time, our kettles needed no scouring on the bottom.

Doris and I were on our knees rolling our bags into the smallest size we could when a friendly "Hello" greeted us over the rail. It was George, the hired man, coming to say goodbye.

"I’ve been on the road myself," he said. And he told us how he used to bum, hop freight trains, and win bike races. He had us quite convinced that we belonged to the same order of hobos as he. "You sure are going to make some hobo a good wife," was his last remark. He flipped us each a quarter saying, "You’ll probably need it." We were thoroughly initiated. We looked the part; we were taken in by a member; we were given a handout. Yes... we were hobos, because we are, as George put it, "on the road ourselves."

We left Johnny’s farm at 7:20 and arrived in Erie at 10:00. Erie was quiet and peaceful that morning. The church bells were ringing and well dressed people were waiting on the street corners for buses to take them to Sunday services. We headed for a gasoline station where we could change into our non-wrinkle dresses and comb out our hair before attending church.

Then, after riding around past several churches, we picked out the one with the most interesting sermon title and entered. The log account of it reads:

We arrived early, so one of the members ushered us into an adult Bible class. We passed from one host to another until we supposed we had met the entire congregation. The sermon was "God and our Troubled times." Very good. We put George’s quarters into the collection tray.

After church, we rode out to the peninsula jutting into Lake Erie, cooked our lunch, and wrote letters on the seawall. All of the people who had shown us hospitality were written notes of appreciation. As the heat of the day subsided, we once again headed west.

On the Road.

The only equipment our bicycles lacked were odometers to record our mileage. Wartime measures had taken them off the market, so we trusted to luck that we might find one on a dusty shelf or even a secondhand one along the way. Inquiries at the auto stores were fruitless.

Now, bent along the highway en route to Ashtabula, we came upon a one-story gray shop with a sign "Bicycle Repairs" hanging in the window. Rusty frames and bike parts leaned against the window from within. The shop was closed for Sunday. We stood peering in, wondering at the prospects of finding an odometer, when a short, fat man appeared around the corner of the shop. It was DeMarco, the man we wanted to see.

"Bike odometers? You’ll never get one of those. Are you girls going very far?" We explained our journey and he immediately became enthralled. "Say now, that calls for something more than leg muscle. I’d like you to come in a meet my wife." The little kitchen was permeated with the smell of garlic and meatballs. "You’re going to stay for dinner," he was deciding for us. "My wife makes the best spaghetti, and we’ll have plenty of beer. Beer is good on a hot day like this." Although the invitation was tempting, we declined in the hope of making more mileage before the day was over. We filled our canteens with fresh water and departed. Afterward, we regretted that we had not accepted. After all, we had no time limit. Why were we rushing?

By evening we arrived in the city of Ashtabula, Ohio. Another state line crossed and our first destination was the telephone booth. We had promised that we would call home on Sunday.

Buffalo rang our number. Someone on the other end lifted the receiver. "Hello Mom," I said excitedly. "Here are your two bikers in Ashtabula, Ohio. Of course we’re all right, Mom, except for very burned noses." I reeled off the list of things we had planned to say. "No, we haven’t any blisters. Yes, I do wear my rubbers. People are very kind to us and there is no need to worry."

I turned to Doris. "They still want to send us train tickets."

"Oh, tell them we are just ‘bums on the plush,’" Doris replied. "If we need any trail stake they can help us out."

The operator called time. The nickels jangled into the box. The voices that carried us home were gone.

Months before we embarked, our friends bonded in a mutual attempt to discourage our trip. "Foolishness!" they called it.

"How are you going to live in one dress all summer? And where on earth will you do your laundry?"

"What’ll you do when there’s no creek to take a bath in?"

"Don’t think you can always make a wet wood fire in the pouring rain."

"I know. You’ll get to Gowanda and wire home for some blister ointment and a feather pillow, and then beg somebody to take your seat and let you stand up on the bus." "Good Lord! A whole summer without mail. I’d die if I didn’t know when Bud’s unit got shipped out."

"Imagine not hearing the top jive on Hit Parade for a whole summer!"

They pelted us with a myriad of queries. We had answers to all of them... well, at least most of them. And for those unanswered, we would trust to the luck we hoped we possessed.

One dress nothing. We were equipped for rain, sun, snow, and swimming. Riding along the road in shorts, letting the wind blow through the toes of my huraches was the coolest form of travel. But those brisk mornings, which were very few, found us bundled in dungarees and thick sweat shirts. And every time we dug for the camera... out fell the rubbers.

What if it was storming? Hadn’t we always found shelter on our hikes before? If we could light a fire on one match, why worry about a little rain?

Maybe we were over confident. Maybe our egos were dangerously expanding. We didn’t wonder; we didn’t worry. We trusted an inner feeling of safety and strength in our independence.

* * *

June 26, 1944

And so it was that on June 26 we were to answer one of those questions. This was the day we were to pick up our mail, general delivery, at the post office at Painesville, Ohio. The post office was a beauty. It was white and modern, and to us it seemed the ultimate of American democracy.

We climbed the steps, passed through the glass doors, and inquired at the window, "Any mail for Popp and Roy, General Delivery?" Hopefully, we watched him reach for the mail in the pigeon holes under "P" and "R".

Thumbing through them, he laid aside some letters. "Roy and Popp?" he inquired again. "Three letters and a post card for you."

We grabbed them up and swung out the door. Like children saving the frosting until last, we went through the business of ordering chocolate sodas in the drug store before we broke the seals. We read them, re-read them, and read them to each other. What a time our parents were having! The war news was almost forgotten, and in its place were maps of the United States sprawled on the tables with the route of the "Two Wandering Mice" recorded. After the mailman arrived, the telephone between the Roy and Popp families was buzzing. Wonderful parents to even bother with such foolish adventurers!

When we entered Painesville, we had passed over a high bridge spanning the Grand River. The swim we had waited for was beckoning far below. Skirting around the edge of the cliff, we watched for a break in the iron rail that might lead to a pathway below, but the drop was sheer and only a few dwarfed bushes clung to the sides. "Let’s go back to the bridge," I said. "There should be a way of getting around the bridge by the abutment."

So we circled back to the huge bridge that spanned the river. Here the land around the abutment that held up the western span of the bridge sloped more gently to the shoreline.

Doris had already dismounted and was trampling through the underbrush in search of a path. "Here it is!" she yelled from under some bramble bushes. "It’ll be tough taking our bicycles down this incline, but I don’t think we should leave them up here."

"Lead and I follow," I exclaimed, pushing my bicycle into the thicket. It was a struggle going down the steep incline through rock heaps and broken glass. The bicycles gathered momentum and strained at our grasp. And then we came out of the tall weeds to the shadow of the concrete foundation. It was cool and moist. The rumblings of the trucks and autos above echoed off the concrete walls. Doris was taking off the straps of her saddle bags and clothes were flying left and right.

"Look where you’re throwing them, Mouse, right into the sand." "Exactly," said Doris, "I’m going to give them a good scrubbing. Have you forgotten that we’ll be in Cleveland tomorrow? I’d hate to have to see a movie in my bathing suit."

I was content to sit and dig my toes into the cool wet sand. The river was warm and lazy. I was feeling lazy, too. I had to admit it was a perfect laundry. Doris was sitting on a big rock in the middle of the river. I got up and splashed my way out to sit beside her on the warm rock and laundered my clothes, too.

"Ablutions of a hobo. And to think housewives have to keep changing the water all the time!"

The evening was cool as we passed through the town. Families rocked in the dark green coolness of the porches. Hoses sent up a shower of spiraling drops that fell, pelting the green grass. Little puddles on the walk mirrored faces looking down: children laughing upside down.

Next to the curb stood a huge chocolate soda four feet high. It welcomed the passerby into the white-tiled creamery. Doris glanced at me.

"Are you awfully thirsty?" I asked.

"I guess I don’t need another invitation."

More coolness inside. We stood before a refrigerated counter containing bottles of milk and cream. A man was polishing a row of glasses.

"A quart of milk, please," said Doris.

"And two large glasses," I added.

A little mystified, the man handed us the quart of milk and two soda glasses. We sat down in a little booth next to the front window. The man, still polishing the glasses, turned to watch us. Doris shook the bottle and poured the ice cold creamy milk into the tall glasses.

"Fill ‘er up." I held out my glass. "Then I can take the bottle back and get the three cents."

We drained it down to the last drop.

The little man swung the towel over his shoulder and clapping his hands to his hips, shook his head. "Well, I never... twelve years I’ve been seeing people drink milk here, but I’ve never see it go like that."

We went out on the sidewalk. I looked at the sky. "We’d better think about bunking." When I said that innocent word, "bunking," we realized only its connotation, a place to sleep, even maybe a comfortable place to sleep. We had been very lucky and had no cause to worry.

Suddenly it was dark and we could find no barns. The stars were all out. It was warm. There was a little school house in a large field. Why not just camp outside? So we unrolled our sleeping bags in the field under the stars in back of the school.

Beware of fields! Beware of fields on a warm summer night! Our bedrolls were very warm. They came from Iceland, so they should be. The night was warm, too. There was no breeze. We laid on top of the rolls under the light cover we had made for them. And then it began.

A hum... a drone... a little black spot hovering between me and the sky. There were millions of them - mosquitoes! They swarmed over us, and mosquito netting did no good. Our arms itched, our legs itched, our feet itched, our faces itched... and still they kept at us. There was only one thing to do - retreat to the hot bed roll. Up came the zipper, down went the head. It was stifling! Sweat began to trickle down my face; my hands were clammy. I peeked out of the hole and saw them still there, still waiting to continue the feast. The moon swung in a great arc. It must have been at least three a.m. The humming of the pests continued.

"Never again shall I spend a night like this!" I thought. "Soon it will be morning. Morning must come sooner or later."

I felt cramped, my back ached, my whole body itched, my face was swollen, and it was hot. Somehow under those conditions I fell asleep, and in the morning I was breathing cool air. It was quiet. The monstrous demons of the night before had disappeared.

Soon we were biking along the road, singing at the top of our voices. We felt good now. The wilting arms of the willows spread a cool archway over the highway. We pedaled through its sun-flecked shadows.

All the songs we had learned as Camp Fire Girls seemed to find their proper place on the open road. Pedaling side by side we kept up an endless stream of songs fitting the blue of the morning, fitting the white of the highway, fitting the wind in our faces, fitting the gypsy song in our hearts.

Along the road that leads the way,

We travel as it wills,

Our hearts a guidepost good enough

To find both dale and hill.

Our hearts are light, our courage high,

The way is good and broad.

Give a cheer! Give a cheer! Give a cheer! Rah!

Hurrah for the open road!

Willowby was our breakfast stop. At 8:00 a.m. the townspeople were preparing for the business day ahead. Brooms swept the papers fluttering to the curb. Water splashed from the window washers’ buckets and ran in little streams down to the curb. A white-aproned clerk piled pyramids of golden oranges against the window. Beneath was the freshly-painted sign, "Oranges - 5 cents." We went inside and bought the two biggest oranges we could find.

The village square was a convenient breakfast spot. We lined up the meal on a park bench. The bran flakes were dry, the oranges pithy. I chopped off another lump from the petrified sugar in the bag. It had weathered the storm, too. Then we filled our canteens at the gas station to wash cups and spoons.

Now we were on our way to Cleveland. Today we would hit our first really big city. We would be "bums on the plush"... sleeping in beds, eating in restaurants, seeing a movie. These things, we discovered, would be well earned. That sun we had greeted in the morning was now high in the sky and baked down on us.

Before entering Cleveland from the east, there is a long stretch of road without trees and with heavy traffic. We pedaled along for a long time, rationing out our precious water. The ultimate effort that day was crossing the viaducts that are near the large baseball park.

But now we were in the city. The streets seemed jammed. The houses were close together. And it was so hot! As we biked along the streets, people turned to look at us and car horns honked, but now we were veteran hobos. We were hardened to the stares of the public.

We saw a man standing on a street corner. He had on a blue uniform with a bright silver shield. People everywhere know him as a "cop," but this should be corrected, for he has another name; he is an "angel." Above his head, although he does not know it’s there, and although some people do not see it, is a halo. We have placed it there because we think he earns it.

From day to day, from town to town, he patiently and cheerfully imparted his information to us.

"Route 42? Well, you see that red stop light down there girls? Just turn to the right there and keep on going. Good luck!"

"Post Office? Why sure, I was going that way myself. Come on along."

"A place to swim? Well you look as if you could really use a swim! Now I’ll tell you, just go down this street...."

Yes, those cops deserve those yellow bands up there above those blue-visored caps. So when we saw this angel standing on a street corner, we naturally sidled over to the curb and greeted him.

"Well, look what we’ve got here!" He exclaimed. "You look like health poster girls! YWCA? Sure, that’ll be easy to find." His hearty voice boomed out directions, and his hands gestured the turns and number of blocks. We thanked his grace and took our leave to the city "Y".

* * *

June 28, 1944

The comfort of white sheets and springs kept us in bed to such an hour on June 28 that all hobo rules were infracted. From the window I looked down upon the maelstrom of the city. Crowds circled the buildings and taxis, trucks and cars moved and halted to the rhythmic scheme of lights. The trolley swayed to a stop and workers stuffed themselves behind the door. Theater lights blinked above the enormous exaggerated pictures of the actors. Mothers, half running to escape the change in prices, towed their children inside.

A gigantic watch hung over the jeweler’s shop. Its hands beat out the movement of the throng. It jerked to the minute, disregarding the seconds between time and rush, rush and time. I moved away from the window feeling tightened and strained, yet amused at their aimless way.

In our freshly-laundered clothes and tight curls, we wove in and out of the parked cars to the southern end of the city. The sight of the markets reminded us of the breakfast we had passed up. Mounds of fruit were heaped up on carts along the curb. We questioned the prices and asked for two oranges. The huckster surveyed our outfits, grinned a toothless grin, and handing four oranges to us he said, "I’ve been on the road myself!"

The rough brick pavement, the veil of smoke, the line of heavy trucks and stop lights proved an obstacle course for us until we reached the open country again. And still the heat did not let up. We wanted to make up for the morning we lost, but the wheels turned slowly. Doris was walking her bicycle up the hill. I stopped to drain my canteen. Drops of perspiration stood out on my arms. My nose tightened from the burn.

It was useless to pedal further. We stopped at a gasoline station and stretched out on the lawn in the cool shade. The heat of the afternoon was intolerable. Little did we know then that the temperature was 102°F, and we had gone thirty-five miles! A barn one mile outside of Medina, Ohio, was our quarters for the night. The quart of fresh milk the farmer’s wife brought us was all we could drink after the strenuous day.

* * *

June 29, 1944

On June 29 our log reads:

We were up at six, because we wanted to get our riding done in the cool early morning. The sun was just rising as we turned out the gravel driveway after leaving a thank-you note in the mail box. We had a bountiful supply of food, so after biking five miles we stopped to cook breakfast. It was a royal meal. There were grapefruit, cereal, bacon, and soft boiled eggs and milk. We hard boiled two eggs for lunch and then did the dishes.

After continuing about six miles, we dismounted to push our bicycles up a steep hill. A heavy truck slowed at the base of the hill, shifted into second gear and met us at the top. Hearing the truck slow down, we turned to see what the driver wanted. A smiling face topped with a shock of blond hair was thrust through the window. "G’morning girls. Is it tough pushin’?"

"Yes sir," we agreed. "We didn’t think we’d find many hills on this road."

"You’re going to find a bunch of them from here to Delaware. They’re building a new road about fifteen miles from here that should be more level. They’ll be workin’ on it today, though, so you may have to take a bumpy detour."

Doris and I groaned at the thought of another day like the one we just passed through. "How would you like a lift?" he asked. "I’ve just delivered a load of hogs and am on my way back home to Delaware."

We were to find our next mail in Delaware. There was temptation, although we thought it would be sort of cheating. We stepped around to the rear of the truck. The slatted sides of the truck enclosed a floor of mud stamped down by a score of pigs. We wondered whether we would be a reasonable facsimile to haul back!

Post Office, Delaware, Ohio. Mail General Delivery. (29 June 1944)

"Sure," we decided. "We’ll go along with you to Delaware. That’s just the place we’re headed for, too."

The driver pulled the truck off onto a siding and climbed into the trailer. He unloosened some straps on the side and said, "Hand up your bike and I’ll strap it to the side."

He leaned over precariously while two of us hoisted the bicycles up to him. How genial he was to offer us a ride and then obligingly haul our bicycles with us. With our bikes secured, we crawled into the cab beside Bob, holding the kettles and knives that would have tipped out in the trailer.

Never before had we appreciated the effortless travel of a car. On the way up every incline my leg tensed and I felt like helping the truck to make the grade. We took turns shouting above the roar of the motor and proceeded to learn about the "Big White" we were traveling in, the four shifts in the truck’s gears, and about the $1,700 worth of rubber in one outfit.

"Once in a while I take my boy on one of these trips," Bob said.

"How old is your boy?" we asked, as soon as we learned about Bob’s little girl and boy, and his wife. We found out that a good trucking job paid well and was secure. "It’s hard to get used to," he said. "You have strange hours and have to catch up on your sleep when you can get it."

Another large truck was approaching from the opposite direction. Bob honked his horn. The other driver honked his in answer. They both waved. We were learning a new code of the road.

We were now on the very summit of the range of hills when suddenly a large city appeared in the valley before us. What was a city of that size doing here? Then we saw the coils of smoke and the numerous factories - war production!

"How about a place to eat at girls?" Bob asked. "This is my usual stopping off place. Come on in. I’ll introduce you around."

We were now to enter a trucker’s stopping off place. We learned that wherever there are many trucks in one spot, you will be sure to find good food.

We sat down at the counter and gazed at the friendly smile of Tiny. Tiny was big - big in every direction. She was the wisecracking waitress who made everyone forget their monotonous night of driving. She was the one who listened to the fellows’ troubles. "Where’s Joe?" she asked. "Haven’t seen him around lately. Had an accident? Not hurt, too? And he with a wife and kid." She filled a cup of coffee and managed to turn around in the crowded space behind the counter. "Nice boy, Joe. Oh, he’ll be back soon. Can’t keep one of these hard boiled truck drivers down!"

Everyone laughed at that, for these truck drivers were not "Hard boiled." They had heavy jobs and hard hours, but they also had families and children, and they had their troubles and their happiness. They were an important part of the makeup of these United States.

Hospitality

The Humble Farm in the Countryside

June 30, 1944 - Gruber Farm

Our shelter for the night was again a warm, comfortable barn. No matter how spacious a barn might be, it is always cozy. Perhaps that is because with so few windows it is dimly lit. Then the musty fragrance of the hay and alfalfa makes it a homey place.

A barn is warm. If it is quiet, you are completely at rest in an atmosphere of reflection and comfort. If the chickens are fluttering about and cackling and the cows are shifting in their yokes, you feel the warm comfort of your animal neighbors.

I sat outside the barn door. The cool breeze of evening wafted across my warm face. Beyond the hedge row and the wheat fields, clouds floated in the sea of crimson sunset.

Doris sat with her back to a leaning ash tree, with pen poised beneath her tilted chin and writing case open in her lap. She, too, gazed at the beauty beyond. Wonderful friend, Mouse. Wonder who else would partner an adventure like this. A shuffle of footsteps came through the tall grass. It was Mrs. Gruber coming from the farm house.

"Good evening girls," she said, touching the knot that tightly held the grayed hair from her forehead. "Won’t you come in and join us before the mosquitoes eat you up?" Her tiny eyes peered at us through the heavy bifocals. A furrow for every worry creased her brow. We heartily obliged and followed her up the flagstone path to the screen door.

"Down Shep, down," a voice from within warned, and a big white sheep dog brushed past us as the door opened.

Mrs. Gruber ushered us through the kitchen into her living room. It was one of those rooms boasting the final payment on the modern chair that fought with the Boston rocker. Grandfather hung in a six-inch gilt frame over the bouquet of faded paper roses. A China doll dressed in red feathers, the latest prize in a bingo game, balanced on the edge of the window sill. It was all neat and clean, but one colossal failure at interior decoration.

"How would you like some ice cream?" a smiling face questioned from around the kitchen door.

"Come in and meet the girls, Clare," motioned Mrs. Gruber. "This is my daughter Clare. She’s living with us while her husband is in the army. My daughter-in-law is living here, too, while John fights in the Pacific."

She rose and went over to the mantel where a row of pictures stood. Bringing them over to us she said, "These are my sons." Four uniformed boys smiled in their paper frames. "The boy you saw driving the tractor this evening is the only one I have left. He’s just nine years old. I don’t know what we’ll do for help on the farm. We lost six acres of corn after the last hail storm."

Her nervous fingers fidgeted with the spoon as we dug into the heaped bowls of ice cream. The mention of the war and her sons deepened the lines of her face. She toyed with the mound of cream.

"It’s been so long now. My only happiness of the day seems to be the sight of the mailman filling the box. There’s Clare’s husband," she said pointing to a picture on a low table. "All of them in it - spare nobody," she murmured.

In vain we attempted to divert the discussion to a more cheerful topic, but rigidly she stuck to her own thoughts.

"I suppose you have sweethearts in the army, too?"

"Yes, we have friends over there," we nodded our heads.

She seized upon our answers. "Where were they? Maybe they knew her boys! No, they were in different armies. There are a lot of men in the army."

After hopefully reassuring her the war would be over soon, we retreated over the damp grass to the barn. It had grown dark, and we felt our way around the hayrack to the corner where our bicycles stood. I unscrewed the flashlight clamped to the handlebar and swung the beam around in search of the pump. We found a water tap next to the cow’s stall.

"This is a perfect bathroom," Doris said, swinging her towel up on the cow’s yoke. "Nothing like having milk bar and powder room combined!"

I ran some water into my cup for my toothbrush. Moonlight flooded through the barn door, so I turned off the flashlight. As I was leaning over the pig pen vigorously brushing my teeth, I heard Doris splashing in her cup of water, then a crunch, then a groan.

"What’s happened, Mouse?" I cried.

"Oh, those confounded glasses. I forgot where I laid them on the floor and stepped on them."

We were both Blind Mice without our glasses, so I could sympathize with her loss. After gathering up the pieces, we groped our way back to our bed rolls.

June 30th was the ideal day. Each day had its pleasure, its adventure and happiness, but the memory of this day has been filed away with those of rarity. We pick it out when we want to relive a beautiful day - a sunny one, with a cool breeze, a blue sky, and the fragrant aroma of open country.

If we want to think about exercise, we remember a long, broad, white highway stretching miles ahead of us, level and smooth. We can feel our legs pumping rhythmically so that soon it becomes a mechanical force. We are in motion - a continuous motion that feels comfortable. The road slips beneath our wheels. The pebbles and gravel along the side of the road become a blur. We are going someplace and we are happy in our effort.

That day we saw the United States. We saw green fields - miles and miles of green fields leading off to the horizon. And across the fields came a stampede of hogs. The hogs were fat, sleek, clean. They jostled along, racing to keep up with each other. Then suddenly they would stop alongside a fence or in the shade of a tree. "What ho there... get along," we shouted to them across the field. And they would start pounding the earth again. Big calico hogs rooted along the fence and scrambled through the rows of corn to keep abreast of the bicycles. Little ones squealed and raced to keep up.

More green fields. More sleek and prosperous hogs for miles and miles of rich, fertile land. We saw the fields of yellow corn, tall and waving in the sun and breeze. There were no houses, no barns. This was the great hog and corn belt of Ohio.

Farther along, two white horses with manes flowing galloped along the fence beside us. It was times like these that Doris and I rode along silently, seeing and feeling all the things that were happening about us.

Trees were sparse, but when we did find one along the road, we took advantage of its shade and the tall grasses below. That was meant to be a short relaxation, but it turned out to be a long nap there by the side of the road. How much a part of the earth we were then! How independent of people and all their accessories. No one else would stop beneath this tree and see it as we did. Oh yes, they would drive by at fifty miles an hour and say, "We have seen it." But in their rush they would have missed the stoney silence of a scene filled with nothing but earth and sky. They would have missed the unmistakable fragrance of a breeze wafting over acres of growing things and the color of wheat under the shadow of a passing cloud.

This was the time we realized that our method of travel was the best. Under our slow pedaling, nothing escaped us, from the change of the pavement at the county lines to the gradual change of the speech dialect from North to South.

If we wanted to talk to someone in a field, we just pedaled over and dismounted. If we were tired, we just curled up under the nearest tree and slept. Bicycle hobos were we!

When we read history, we look back on our ideal day and think how much better it is to seek out the history, to be wide awake and feel the romance of a nearby situation.

I was the first to notice the houses. "Look, houses without shades and not painted either. That seems strange."

I saw an immaculate farm yard, a fence, a gate and a clean driveway. The windows of the house sparkled. Ornaments here would be superfluous. The very cleanliness was beauty.

There were more houses, and then we saw an owner. He emerged from the house - tall, lean, bearded, wearing a broad-brimmed hat. Two healthy, robust children were following him. Their hair was trimmed as though patterned around an overturned bowl. Long bangs framed their foreheads and blue eyes sparkled from beneath. What was all the cleanliness, orderliness and simplicity? We found the answer. This was an Amish settlement.

Many such colonies as this one began in Ohio before the Civil War. Some groups came from Pennsylvania, others from Virginia. In 1767 Christian Blanch founded a settlement near the headwaters of the Ohio, and many Amish drifted from there and established new colonies in the nearby states.

Then, in 1852, a congregation from Pennsylvania was organized in Ohio by Ephraim Hunsberger. Many of these Amish colonies moved on to Indiana and Illinois, but here was a group that remained with their faith, beliefs and customs intact around Plain City, Ohio.

We decided to call on our Amish neighbors. Perhaps we could have our lunch on one of their lawns. We approached the side entrance of one of the farms. It was the kitchen, and it seemed overflowing with people. We were warmly greeted and the mistress of the house explained the great activity.

"We are having a community dinner after church and all of the women have gathered here to clean chicken and help prepare the meal. Yes, certainly you may have your lunch here. There is a nice shady tree beyond the hedge."

These were indeed the friendly people.

When we dream of easy domesticity, we see again that afternoon siesta beneath the shady tree just beyond the hedge. Put cheese and lettuce together for sandwiches, pour the creamy milk from the canteen, open a can of fruit, unwrap a candy bar and behold! We have a delicious lunch. And there in the soft grass we darn socks - the only two pair we have - sew the only button on the only pair of overalls and we are finished.

Voila! This is the life! Stretch out full length and relax, listen to the birds sing, watch the clouds float by. No troubles, no worries, no cares. Just be happy and be glad to be alive.

A friend wandered into our ideal day. We found him that afternoon in the lovely town of London. But did we find him or did he find us? Doris and I were standing on a street corner with our bikes when he came along. He was an elderly gentleman especially interested in our bikes, and we were especially interested in him.

"Now where would you be going with those bikes?" he questioned. We dropped all false pretenses and came right out and said, "to the Mississippi!" His eyes twinkled. "I know that river. I used to work right near her on the Ohio. I could tell you a lot about it. Come on in and have a bite to eat with me, won’t you please?"

We did. We had met John L. Park, a guard at the prison farm nearby. We discussed our past experiences and he helped mold our future ones.

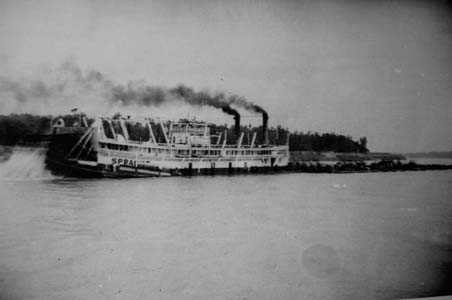

"There are still many boats on the Ohio and Mississippi," he assured us. "Why don’t you girls buy a Johnny boat and go down the river a’ways? You can pick up a John boat anywhere around there."

More romance! More adventure! We mentally decided to find out what a John boat was, buy one and proceed down the river.

"The very best of luck to you girls," our friend said in parting, "and drop me a card to let me know how you are getting on."

Our conception of a perfect day includes an event that is different and exciting. This day was not without it. We remember how the twilight gathered and how we pedaled along the road just outside London, Ohio, searching for a night’s lodging. But alas! It was Saturday night. The farmers had all gone to town, and there was no one of whom we could ask shelter. It was getting darker and darker. We knew we must find a place somewhere.

Then one of our ambitions was realized - to be just as sacrilegious as we could and sleep in a cemetery. There wasn’t much of a choice in the matter this evening, and Doris was willing.

Kirkwood Cemetery, just outside of London, was a hilly little "bone orchard" surrounded by an iron grilling. The gate was open. We picked a bunch of posies, to look more appreciative, and we rolled past the caretaker’s house. Toward the back of the cemetery the monuments grew larger, the trees more enveloping, and ourselves more obscure.

"Let’s take a look around," said Doris, hopping from her bicycle. I followed her over the slope, surveying the habitats of the Smiths, the Wolfes, and their ancestors.

"Look at that skyscraper over there, Mouse," I said, pointing to a tall monument. "That’s not cozy enough to sleep under though."

"Let’s pick out a nice respectable family and spend the night with them," Doris suggested. "How would the Kanes do? No, they have a daughter still living. She might walk in and request her plot at any time. Here’s a family of six with the aunts and uncles thrown in. No, that’s too crowded. How does this suit you over here, Mouse?" On a knoll a giant evergreen spread its branches over the large granite monument of the Harrison family plot. Soft green grass sloped toward the drive. I surveyed the location to give my thorough approval. It faced the setting sun, a fancy white bench leaned against the tree, and isn’t that a pump I see through the tombstones? All the conveniences. So near to heaven and rent free!

"Well, let’s move in," said Doris. We hauled our bicycles up the slope, leaned them against the tombstone and untied the bedrolls. There were two headstones at the foot of a grave marked "Father" and "Mother."

"Choose the one you want, Mouse. A soft spot for a change, eh? No sticks or stones, just bones!" Doris was sitting on a neighbor’s tombstone putting up her hair. We never neglected our good neighbor policy. I shut my eyes just for the effect - just like home. I opened them. A breeze caught the G.A.R. flags on some of the graves. Doris’s sleeping bag looked like a mummy case. What if the caretaker came around to check the cemetery? He’d run a mile. We might even start a ghost legend of London - Angels on bicycles!

I rolled over and looked up at the engraving: "Benjamin Harrison... Died 1885." I paid my respects to him and shut my eyes.

Now I lay me down to sleep

Gravestones at my head and feet.

If I should die before I wake

Just bury me here

For pity’s sake.

Slept in Kirkwood Cemetery, Ohio. (30 June 1944)

* * *

Morning, July 1, Kirkwood Cemetery

I opened one eye slowly. A forest of gray obelisks surrounded me, and the early rays of sunlight elongated their spindly shadows. A caravan of ants kept up their steady trek over my sleeping bag, their massive shadows marching along beside them. I opened the other eye slowly. Doris was still asleep in her sack. I slipped out and dressed quickly. The pump was not far away, so I gathered up my toilet articles and set about the morning scrub-up. Brushing teeth over a tombstone would have been an uncanny sight for any early morning cemetery visitor, and to have someone find me standing there with one foot under the pump would have been quite embarrassing. Fortunately, I had no such experience, and when I returned to our family plot, Doris was already up.

"How was your night?" I inquired.

A growling yawn and a long stretch was her first response. Then she replied, "I feel like a mummy. Those ants trooped in and out all night."

"Well let’s pack up and move out of here before they hand us a shovel."

This morning we had business to attend to. We immediately contacted the postmaster in the town of London and soon all the workers of the post office were aware that an important package containing a pair of glasses was to arrive in the mail that day. In fact, every hour we appeared at the package window and were informed, "Not on this train, girls. Try the next one at 9:30."

This period of waiting was not an unproductive one. We had breakfast on a sunny patch of grass in the town park. We rode up and down the London streets waving greetings to the townsfolk who now accepted us as a customary part of the community. We shopped in the "Five and Tens" and bakery shops; we feasted on our cheese sandwiches on the steps of the county building.

At twelve noon the post office closed, but the remaining workers were still pulling for us. As soon as the glasses arrived, one of the workers would leave them at a nearby gas station for us. Where in any large city would we find such kindness and service?

Yes, they at last came on the one o’clock train. We left our neighborly village and once more, with the world in sharp focus for both of us, journeyed on our way.

The contour of the land gradually changed from the level lake plain to rolling farm land. Mr. and Mrs. John Bush’s farm was set on a curve of the highway going to Xenia, Ohio. It was a different kind of a farm than we had seen before. Black and white geese filed along the fence, chattering and flapping their wings at the intruding chickens. Five little pigs rooted in the mud. Inside the barn, pink-nosed rabbits sat in their cages.

And then a collie pup bounded through the gate and greeted us with a thrashing tail. Mrs. Bush followed. Mrs. Bush seemed a little old fashioned. She pondered our situation and seemed dubious about the fact that two girls would travel so far and sleep in barns.

"Well," she said, "I don’t see how you could be comfortable in a barn. Don’t your parents worry about you?"

"Yes, they do worry about us," I answered. "However, we write them once a day and telephone them once a week so they will know we are all right. And now that we have come this far safely, they are more assured that we can take care of ourselves." Mrs. Bush smiled. "Won’t you let me fix up a mattress on the front porch? It would be a lot more comfortable. We have plenty of blankets to give you."

We explained to her how much we enjoyed sleeping in barns.

"I just can’t understand it, but you go right on in and use whatever you need." She held open a garden gate and we walked down a stone path past a raspberry arbor to the barn. "Meet our visitors for the night, John," she said, drawing us around to the stalls.

Mr. Bush was milking the cows. Six little kittens sat in a row with tails curled around their toes, crying and blinking. "This is our cafeteria," said Mr. Bush. "They’re waiting for the next pan of milk."

He filled a pan with warm foamy milk. Immediately the kittens all jumped into the pan, stood in the milk and lapped for all they were worth - white whiskers, white feet and rounded stomachs.

Mrs. Bush guided us through the shed to the hayloft still anxiously questioning us. "Where do you wash up? How do you keep your clothes clean? In streams? But you don’t have hot water."

She disappeared and a few minutes later called us to the back porch where we found tubs of hot water, a wash board, soap flakes and a wringer. How good it seemed to our feminine minds to immerse our arms up to the elbows in that hot sudsy water! Doris washed, I rinsed and hung the clothes out, and Mrs. Bush hung some of the clothing up to dry by the hot stove in the kitchen.

By eight o’clock the geese had all waddled back to their roosts, the squealing pigs lay in a heaving mass beside their mother, lamps burned in the farm house, and two Mice were sound asleep in the hayloft.

* * *

July 2, 1944

The next morning Mrs. Bush invited us into the kitchen to breakfast with her. "Be careful, girls, of the automobiles on the road," she warned. "Goodness! I feel as though you were my own daughters. You must write and tell us of your adventures." They waved goodbye to us as we rolled down the road. This day we did not look like hobos. We were adorned in our one and only non-wrinkle dresses and very clean white ankle socks, for this was Sunday - church day. Up and down hills we went to Waynesville, where the tolling of bells drew us to a little brick church on the hill.

We sped up the hill, leaned our bicycles against a tree, patted a loose curl into place and sedately walked into the church. We slipped into a rear pew. "Page Number 105," boomed from the altar. Someone passed us a hymn book, a Methodist Hymnal. We had not found out what church we were in until then.

After church Doris and I held a pow-wow. "Let’s eat out today. Let’s have a real good Sunday dinner," said Doris.

"Can we afford it? I have only two dollars left before I cash another traveller’s check."

We looked in our basket and drew out several shriveled dried up carrots. Further on down, under a tin can rested some moldy potatoes. There was still the Mother Weed’s Noodle Soup. We looked at each other. Our clean dresses getting smoked up by a fire? The Number 10 tin to scrub when the soup was all eaten? No meat? What for dessert? Fifteen minutes later we were reclining in comfortable chairs looking down on plates garnished with roast beef, mashed potatoes, gravy, corn, salad and rolls. Beyond the screened windows was a blue artificial lake dotted with row boats. From a juke box a top orchestra swung out our favorite tune. Tomorrow would be time enough to cash that check.

We were in no hurry. The peppermint ice cream was good enough to rate a second dish, the little lake was pretty enough for a stroll along its edge, and the grass on a nearby hill was just soft and cool enough for a two-hour siesta.

Never did we worry about the night’s shelter. Pity the poor people who must stay in hotels and tourist homes! What if none showed up when they were ready to stop for the night? What if the hotels and tourist homes were all filled up? The prices might be high, and what about the inconvenience of unpacking and packing a suitcase? Pity the elite of the road who whiz by in shiny automobiles with their eyes on the mileage gauge, and who only know the features of the trip by the size of the hotel rooms and the restaurants of each town.

Here on this grassy hill we laid, not knowing where we would spread out our bedrolls in the next four hours. All we knew was that we were on Route 42, between Waynesville and Lebanon, Ohio, and about thirty-five miles from Cincinnati. What we did not know was that we were near the town of Mason, and that just outside of that town was a beautiful home and barn, and that the owners were Mr. and Mrs. Tompkins. But once we ended our siesta and biked on into Mason, we could not help but notice the Tompkins home. It was on a hill, and following the Victorian style of architecture, it was large and gabled. We paused just to look at it, and then we noticed there was a barn nearby. Would we possibly be accepted here?

Mason, Ohio Route 42. Farm of V.W. Tompkins. (2 July 1944)

Accepted? That is not the word. Mrs. Tompkins does not accept, she energetically welcomes people into her home and into her heart. She is a thin, spry, and extremely active little person, whose eyes twinkle and whose smile constantly reassures you of her kindness and understanding.

"My," she exclaimed, "that’s just the kind of trip I would like to take, just what you girls are doing. Good healthy exercise," she declared as she made us comfortable in her deep living room chairs.

"I’d like you to meet my brother, Mr. Bowyer. He writes poetry."

We stood up and shook hands with Mr. Bowyer.

"Have you ever been in Mason before?" Mrs. Tompkins inquired.

"No, this is our first trip south," I answered.

"Well, we have a nice little town, but the place of most interest is the W.L.W. radio station."

Before we knew it we were all in the car on our way to the W.L.W. radio station. They told us this was the most powerful broadcasting station in the country. We circled the maze of towers and met some of the Tompkins-Bowyer relatives. We had been lying on a hill of grass four hours ago, but now we were part of a family, riding around town in the car, discussing rain conditions for the crops and new neighbors. We drove up the drive to our new home, and brought our miscellany of wash clothes and towels into the house to wash up for the night. They tried to persuade us to sleep in the house tonight, but we decided to roll out our bedrolls on a mattress of corn stalks in the spacious barn, with Brownie the dog at our side.

* * *

July 3, 1944

Cincinnati was only 23 miles away, so we made it by eleven o’clock the next morning. It was a city of hills and brick pavement. Sweating up the winding red streets behind the swaying trolley and bumping down past the Baldwin Piano Company, with tin cans jangling, we flew. Our hair was in pins and our overalls were getting too warm, so we looked for a place to clean up. We looked for one of our havens.

Throughout the United States there is a network of oases. They are the havens of the destitute and weary. We are speaking of that great blessing, the gasoline station. No matter where it may be, how many gas pumps it may have, it is as typically American as ice cream, hot dogs or the World Series. But it has broadened its main function of filling up gas tanks and pumping air. Now there was, in its inner sanctum, a supply of soda, cracker sandwiches done up in cellophane for five cents, candy bars, sun glasses, and tablets to keep the drivers awake nights. Most important of all, somewhere in the vicinity of this oasis will hang a sign, "Rest Rooms." These little stations are very welcoming, but first we must establish a beachhead.

"Hello, what’s this?" some man in greasy overalls would say, and we all would get started in a conversation. Meanwhile, he would be checking the air in our tires and giving us weather forecasts. Then we would park around the back and bring forth from various bags and baskets an array of towels, tooth brushes, soap, a clean blouse, dirty socks to be washed, makeup and comb. Hoping that no others would be in need of our cubical, we took sponge baths and washed our clothes. Socks were hung on the bike handle bars to dry. We were completely at home! Never will we forget our friendly gas stations!