My post-college-graduation trip took me straight down a meridian to Peru.

With just a handful of highway maps printed off the internet and a rough plan to see three countries in seven weeks, I got off my plane and wandered off into the night.

to the index page

Toss out your romantic visions of a solo traveler in the Andes Mountains, carrying enough cash to be filthy rich among the locals, traveling freely every day with no plans beyond the next meal, exploring ancient ruins, visiting famous cities, eating the best foods, staying at the best hotels, and partying the nights away to cerveza, salsa, and soft Spanish rock. Think instead of lonely wandering, watching for thieves, fearing pickpockets, fending off beggars, and learning to trust no one no matter how good a friend they seem. Think of hard beds and missing toilet seats and food poisoning and overcrowded buses with windows locked shut and bitterly cold mornings and no hot water for weeks at a time and no one to speak with in your native language. Remember, the most beautiful places are the most difficult to get to.

I hadn't planned to go alone. It isn't particularly safe to travel solo, and it is absolutely miserable being sick and alone and on the move in a strange place. But Erin had landed a summer volunteer position studying birds for the USGS on the island of Hawaii and though I'd already bought her a ticket we agreed that it would be good for her to take the position. I'd be traveling alone, my two-month romantic adventure through paradise reduced to a solitary tour of silence, and as it turned out we didn't see each other again but for one final weekend in August. It was with some disappointment that I shook hands and parted with my father in a light rain at the Poughkeepsie station. From then on I knew for nearly two months I'd have nothing but my 25-pound backpack and the clothes I was wearing. On the train to Grand Central Station I shared my row with a freelance photographer going to Trenton to shoot for a women's magazine. He'd barely made the train and was a little shaken up, so with halting, excited words he told me about his work. "Pretty pictures," he said. He asked where I was going and was envious when I told him. When we slowed to a stop at stations the faces of waiting passengers on the platform slid by, blank expressions on their faces and wet concrete, dripping green leaves, and the slate gray water of the Hudson River behind them. Everyone was going someplace and most were silent, aware of the many hours of travel ahead. I sat quietly for the rest of the ride and hurried through the Terminal until I found the way to Penn Station via subway. I was nervous about getting to the airport on time, but I arrived very early and checked in. Sitting at the gate I began to feel as if I'd been there before - the chairs and tables were different but the architecture seemed familiar and the murals on the wall were definitely something I'd seen before. Then I remembered when it was: I flew Continental to Mexico City the year before and departed from a nearby gate. It seemed so long ago. Now, once again, I was headed south.

My flight to Lima had many empty seats and I had three together to stretch out in but no one to talk to. Flying down the meridian we had excellent views of the low sun casting shadows and shimmering off the Caribbean Sea below. The sun set as we crossed the Caribbean and it was completely dark when I looked out my window and saw the lights of Panama City below. I began to feel very far from home and increasingly nervous about what I would do upon arriving in Lima late at night. There was a time difference because the States was on Daylight Savings time, so it would be even later when I arrived in Peru. Fortunately customs and immigration did not delay me and my backpack arrived safely. I changed some money and was snagged at the Tourist Information desk, where a pretty girl who spoke English described all my accommodation options. I asked about the bus to Huancayo and was told that there was trouble there - striking teachers - and that I should not go. Also I was advised against going to the old city center, where there would be demonstrations every day. It was enough to convince me to accept a bus ride to a hostel in the financial district of Miraflores, affordable and safe. The bus drove through the dark city and I was surprised by how much it looked like Mexico City. The dirty streets were lit dimly by orange sodium lights and people wandered in and out of dilapidated brick shacks. I noted that many young people were out and they dressed in stylish clothes, in spite of the poverty they walked through. This is Peru, I thought. It didn't seem so foreign anymore for some reason and I slept well, content in my new home. I wasn't surprised the next morning when the girl from the airport counter stopped in at the hostel to chat with the manager.

After a light breakfast of dry bread with jam, juice, and tea I agreed to follow a woman from the hostel to a tour agency. Everyone has friends in the tourist business and they throw a wide net to catch our dollars. At the agency she took a sheet of paper and began planning out my entire trip! Once she learned that I was not going to buy a tour and only wanted a bus ticket, she crossly sent me to the corner for a taxi to the bus terminal. But, I'd gotten the bus departure times and learned a little more about the political situation: there was a presidential convention happening in Cuzco and strikes and protests had all but shut down Cuzco and some of the hill towns. An English woman headed home said she'd been caught in a cloud of tear gas, but it was a casual comment and she went on to tell me about how beautiful the city was and assured me that I'd find many affordable places to stay. I was disappointed about not getting to see Huancayo and Ayacucho but also there was also a warning by the US State Department, several months old, regarding Sendero Luminoso activity in that area. I'm no fool, I thought. I may be a bit overconfident marching in here all alone with no plans but I'm not going to walk into trouble on my first day in the country. Instead I made plans to go to Cuzco via Arequipa.

That meant riding a bus 26 hours south, east, and then north again. Departures were in the late afternoon. It was still early in the morning so I walked around the city for a while but I'd heard plenty of stories about bag-snatchers in Lima and was eager to leave town and get going with my travels without any mishaps. Miraflores was misty and wet and nothing was open early in the morning. I eyed the taxis carefully, trying to discern whether or not there was any reason not to hail a cab from the curb. All the guide books always say it isn't safe, but I saw dozens of hard-working young men driving around trying to earn enough money to support their families. In seven weeks I only had one driver who was dishonest and never did I feel unsafe. I'm not good prey though, at least appearing capable and confident and aggressive in my bargaining. I took a taxi to the Ormeno terminal and bought a ticket for a 4pm bus, then set out to find food. I was in a residential area so there were not many restaurants and of course no one else wandering around with a backpack. Seeing several cevicherias, I chose one and ordered myself a big plate of ceviche - raw fish marinated in lime juice with red onions, chiles, and sides of roasted and boiled corn, sweet potatoes, and fried bits of fish. It was acceptable, not amazing plus I knew I shouldn't make a habit of eating raw fish in Peru. I was just waiting to get sick! At the restaurant I saw a television news clip about protests in Huanuco showing tires burning in the streets and huge crowds of people. It made me wonder what I was getting myself into, so far from home with no way back until July. I walked nervously for the rest of the afternoon before returning to the bus station.

Again I found myself in the awkward situation of the traveling photographer: It's disrespectful to aim a camera at a stranger, for he or she is not a creature on display. I did my best to capture some discreet photos of daily life around me, but one really must experience the streets and cafes and markets first-hand. Besides, I reasoned, much of the world looks like this: muddy streets, corrugated metal and rough bricks, stucco, hazy sky, open-air markets, trash in the gutters, and well-dressed beautiful people walking the streets. The girls wore tight jeans and little shirts, temperatures were in the 70s, and I was quite content about both these things.

The bus was a comfortable double-deck vehicle with a toilet and televisions. There weren't many passengers and I managed to take my pack on and stow it beneath the seat. As we passed through towns we picked up more people, so I soon lost the empty seat beside me. Before darkness fell I peered out my window at incredibly poor shantytowns in the desert. On concrete water towers atop the sandy hills, \ was written in blue paint. Living conditions were better than those I'd seen in East Africa, but I was happy to stay on my bus. We passed soccer games in sandy arenas and hills so dry there were no washes, no eroded gullies, no plants; just dust and gravel. Waves crashed on the beach and both the sea and the sky were slate gray. The bus sped along the two-lane road into foggy hills and darkness. In towns along the highway the orange glow of streetlights illuminated crowds of people gathered about the markets and vendors who served passing buses and trucks.

"Seven-thirty in the evening somewhere along the Pan American", I wrote in my journal. "Stars overhead, mist has cleared. Passing trucks and buses honk a warning before blowing by in the night. We pass bicycles, sometimes motor trikes. The lanes are narrow but the traffic is fast. At villages people load and unload bags from the cargo hold and I'm very happy mine is under my seat. All's well. Stopped at a depot for a while. I'd have liked to get out and walk around, but I'm alone and shouldn't leave the bus or my bag at night. I struggle to understand the rapid announcements and watch other passengers for clues. Good thing it's a direct bus."

A couple hours later we stopped beside a restaurant, and a short time later styrofoam boxes of food were distributed. There was rice, potatoes, and some sort of meat that I couldn't identify. It could have been poultry or pork and was so bony and grisly that I had trouble eating it with the plastic fork they gave me. I ate every morsel, hungry and not knowing when I'd eat next. In Nazca at midnight many people got on, most of them tourists. The man who sat next to me spoke only Spanish though and so I rode on in sleepy silence. The lights were turned off and I dozed in short intervals as we rolled through misty desert and climbed over the hills on winding roads. Eventually I slept a little, and when I woke the sun was about to rise behind distant volcanoes. We were still in the desert though, the huge desert running all the way along the coast beside the Andes Mountains where the only moisture must come from the Atlantic, cross the great forests and steppes, and rise over the high cold mountains. Salt deposits shone in the gullies and only a few withered plants struggled to survive on the roadside. We roared along, trailing dust, passing blindly at corners and hillsides and, once, in a tunnel. People and cars darted out of our path at the last moment and it occurred to me that drivers from the States unaccustomed to this flow of traffic would instantly cause mayhem and destruction. I felt safer riding a bus than driving, enough so that the danger was thrilling. We passed scores of wooden crosses, each marking the site of a fatal accident on the narrow highway and a reminder that such things last a long time in the desert - or maybe they just happen all the time. It was a harsh place.

Traversing the same road seven weeks later I would be unimpressed by the desiccated landscape and the dusty towns struggling to stay alive along the highway, their only source of nourishment and the sole reason for their existence. Many places are truly beautiful, when a special combination of light and rain or snow or other natural elements reveals the character of the setting and the things that live there. It is for these moments that I travel. But also there is the attraction of new and exotic and exciting things one has never seen before, an infatuation born of ignorance that dies out quickly. It was with this attraction that I peered out my window until my neck was stiff from the awkward angle, succumbing myself to the ethnocentric fascination of the traveler just arrived.

For many kilometers at a time the road ran straight, then suddenly it twisted its way into hills and down sharply into deep trenches in the earth lined with velvety green fields and scattered trees and a lazy river. Just as suddenly we would climb the far side and resume our course through the dry flats. I marveled at the woven cane mats forming walls and fences around huts that had never felt rain. The split canes were bunched in sets of four or five, creating a checkerboard pattern that I found pleasing and sketched in my notebook. Maybe someday I'll have a screened porch of split canes like the ones I saw in the desert of Peru. The design was purely functional, and this made it very appealing to me because its pleasing appearance was not for show. The design speeded the weaving and was necessary because the stiff split canes and reeds could not be bent sharply for a tight weave.

Before 8am we were in Arequipa; the bus was navigating slowly through narrow side streets to pass around a protest in the center of town. I could understand little of the rumors circulating through the bus as we bumped and jerked through alleyways where a double-deck bus should never go, but I could see distant crowds of people milling about in the streets and I assumed that, as in the previous days, they were gathering to protest low wages. Arequipa was a sprawling city of mud bricks overshadowed by craggy snow-covered mountains and it was surprisingly green. Fed by a river, emerald fields and streets of palms were a welcome change from hundreds of kilometers of dusty brown sand. Also there were constructions of white limestone blocks, rude walls with mud mortar and lovely churches built from carefully dressed stone. The "ciudad blanco" lay upon a bed of lovely limestone of a cream color with large gray inclusions that lent a rough texture to the cut blocks used throughout the city. At the bus terminal we stopped for 45 minutes. I was alarmed at first because we were all told to get off as the journey had ended, but upon questioning the stewards I learned that my continuing trip would resume from another gate. The terminal was packed full of travelers, many foreigners hauling large backpacks like myself. No one paid me any attention unless I lingered near an exit, where lurking taxi drivers solicited my business with admirable perseverance. Seeking food, I found little but packaged snacks and settled for stacks of dry crispy flatbreads cemented together with a sugar glaze. They crumbled instantly and created a mess and made me thirsty. I wanted fruit, or a sandwich, but none were to be found at the station. I bought water and passed the time in a departure lounge, where a group from Germany was excitedly reading passages from their guidebook. I thought how superficial it was to travel as if on a treasure hunt, darting from location to location as if the entire place were some sort of exhibit, and I was glad I'd never brought a guidebook.

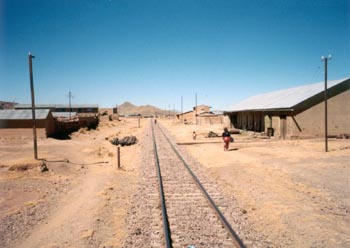

We boarded the bus and I again succeeded in stowing my pack safely under my seat. Once outside the terminal we stopped to take on fuel and I looked out the window at the tall snowy peaks to the West. I would have loved to linger and hike to their summits, but for some reason I felt hurried. I had two intentions to make good upon: visiting Machu Picchu and getting to Puerto Maldonado in time for my rainforest tour, and in this uncertain land I could not leave enough time to accommodate all possibly delays. The next 8 hours passed through the most beautiful scenery I saw during my entire trip. We climbed out of Arequipa past thinning mud brick and stone block shacks, rounding the shoulder of a mountain and climbing high over a pass. Trucks with excavating equipment crept slowly up the grade and we soon arrived at their destination: a rockslide had poured hundreds of cubic yards of rock and dirt onto the road. Our bus lurched onto a steep ramp compacted from the debris and clambered over the obstacle in a cloud of dust while heavy equipment labored to uncover the pavement far below. The road was narrow and winding but well-maintained. Stones lay on the roadside every 10 meters, painted with the number of kilometers to someplace. Beautiful rugged peaks rose from the golden grassy hills, fluffy white clouds scudded across a brilliant blue sky, and ice on the glaciers sparkled in the sunshine. The lakes were as blue as the sky and nowhere was there a speck of dust in the air. At a gurgling stream the bus halted and a man with a bucket fetched water, probably for the facilities on board. Birds wheeled and turned among the grasses and occasionally we passed scattered herds of cattle and llamas. We passed train-stop towns, herder villages, and people peeling back sod, pressing the dark wet soil into forms, and setting the bricks aside to dry. People dressed in brightly colored Andean textiles darted in and out of rough stone huts, their heads turning to see the bus go past, their faces gone in a flash but imprinted in my memory.

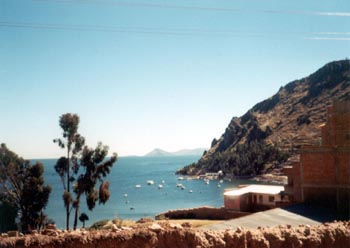

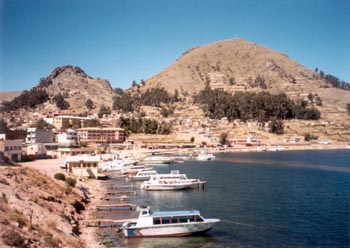

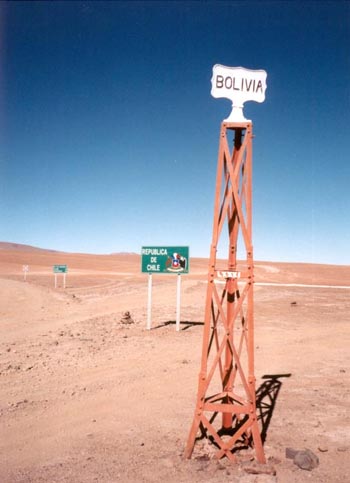

On curves the bus swayed and on the upper deck I feared it tipping. Eventually the land flattened and we sped on straight roads to Juliaca, where the brick industry was thriving outside of town. Shimmering columns of heat rose from kilns built from the same mud bricks they baked. Neat rows of rectangular blocks, stood on a short side to expose the maximum area to the air, lay beside trenches in the grass. The town was very colorful and full of smiling youths. Riot police with their helmets and shields held casually aside watched us pass. The late afternoon sun brought out rich colors in the market stalls and I looked out eagerly upon the great diversity of goods for sale. We stopped several times for passengers to come and go, then pulled onto the main street again and turned south towards Puno. The short winter day had sent the sun speeding to the horizon and as we skirted a marsh and climbed a hill overlooking the edge of Lake Titicaca the shadows of distant peaks were getting long. On the horizon, in Bolivia, I could see the snowy jagged peaks of the Cordillera Real. Pulled in two directions, to Bolivia and to Cuzco, I promised myself that I would return to this place and go see for myself the snows beyond the lake.

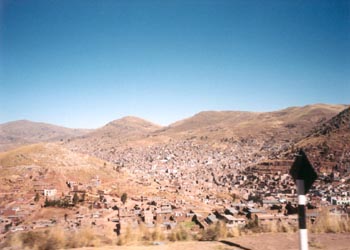

Rounding a bend in the road I suddenly saw all of Puno nestled in a bowl beside the Lake. The entire city seemed to be built of mud brick and only the deep shadows from the low sun saved it from blending invisibly with the brown hills. The bus descended to a terminal and everyone else got off. I was the only person going direct to Cuzco and I regretted it, preferring to catch some rest and find a safe place to spend the night before darkness fell. This I could have done, but being an unsure and conservative traveler I thought it best to save money and time and use the ticket I'd bought. After all, I would be back to Puno in a few weeks at most. The stewards shared their meal with me, another styrofoam box with an unknown meat and potato and rice which I ate hungrily. They said we would be in Cuzco in four hours, a figure I found hard to believe when looking at a map and knowing how long we had traveled from Lima to Puno. But the road was a more or less straight shot down the valleys to a lower, warmer climate and we made good time. Restless and impatient I became increasingly desperate in the dark bus, willing every approaching light to be the outskirts of Cuzco. Hours passed like this. It was very dark, with lightning flashing to the east but always stars above. I was hungry and exhausted and worn from so many new sights and so much time sitting still. Our arrival was rather anticlimactic after so many disappointments as we sped through each town I hoped to be Cuzco. It was late at night, I had no plans, and the terminal was nearly empty. Several taxi and hotel solicitors approached me and I agreed to one, sharing a taxi with another man just arrived. A private room for 20 soles was the right price, but the driver nearly tripled my taxi fare. I paid it unknowing. My room was small, paint was peeling from the walls and ceiling, and both chairs in the room were broken, but it had a bed and blankets and a bath. The shower was heated by a dangerous-looking apparatus consisting of a bare copper blade switch with a ceramic throw tab, 220-volt supply wires, and a shower head heater with a temperature adjust switch. One would presumably reach up and adjust the temperature while showering, but I certainly was not going near those wires while wet. I slid under the covers and was soon asleep.

I was awakened at 6am by other tourists noisily exiting to catch the train to Machu Picchu, but having no ticket myself I was stuck in the city with time to rest and enjoy a warm shower. When the flow was set to trickle like a lawn sprinkler, the heaters added enough heat to be pleasant though the washing power was diminished. Refreshed, I went to the train station and bought a ticket to Aguas Calientes for the next morning, then wandered around trying to get my bearings. Hundreds of police manned the streets, carrying shields and sticks and gas canisters and guns, riding round in the backs of military trucks and drilling in the plaza. Soon after I walked through, they took positions at the corners of the plaza and prevented all pedestrians from entering the center area, restricting passage to the sidewalks beside the shops and restaurants. It was quite effective at preventing the assembly of protesters. I walked back and forth between the station and the plaza, exploring side streets and markets. The San Pedro Station is a meeting place for adventure tours, and 4WD vehicles came and went loaded with rafts and mountain bicycles. Vendors of cheap souvenirs also lurked outside the train station, hoping to catch the timid buyers who seldom left their hotels and buses for the duration of their fully-guided tours. I bought quinoa con manzana and some warm cakes from two girls on the street corner. The drink was thick and syrupy but not overwhelmingly sweet, though it left my thirst unquenched. The two girls were selling the same thing just yards apart and advertising sweetly to passers-by, and I was faced with the difficult decision of whom to buy from. It seemed improper to pass one and then buy from the next, even if I'd simply been debating whether or not I wanted food, but also to buy from only the first would leave the other girl looking on without a sale. I bought drink from one and food from the other and was on my way shortly, reminding myself to make such beverage purchases early in the morning before dirty glasses had clouded the wash buckets.

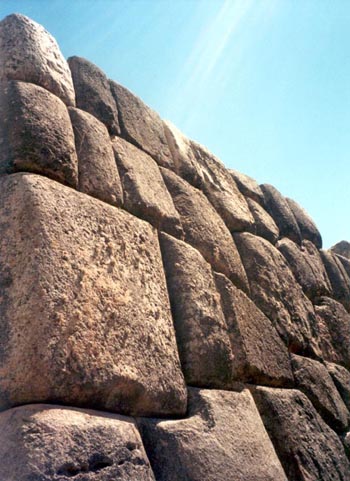

It was early and the shops and internet cafes were not yet open, so I walked up the hill toward the ruins of Sachsayhuaman. Or so I thought, but soon discovered that the ruins lay across a deep ravine. I continued on hoping that a path might go across without going down, but as I got farther from the city center I became entirely out of place. People started asking me where I was going, thinking I must be misdirected, and all eyed me suspiciously. Indeed, I was a stranger who didn't belong in these parts. I took off down a trail into the ravine intending to cross, and along the way a man told me how I could go on footpaths. Farther on I met two women and some children on the path; they advised that I watch for dogs. Finally I escaped from the ravine and walked through cropped pastureland and stands of eucalyptus, happy to be away from the press of people and traffic. I ate some oranges I'd bought from a vendor at a fraction of the cost they went for in the markets in town, realizing that my water was nearly gone. I climbed higher and reached a paved road, looked around, and saw a truck full of police beckoning me to their roadblock. There I learned that there was a presidential convention celebration at the ruins and I could not proceed yet. They were friendly, though, and I chatted with some as I sat in the shade and waited. Across the valley on an opposite hill I could see a gathering of perhaps 200 people making as loud a protest as possible. Fires smoked and occasionally noisemakers went off but the wind and distance muffled the disturbance. After half an hour or so they spoke with a descending photographer and said I could go on. At the ruins I threaded my way past a mass of press trucks and people, peering over a fence to see colorful flags in the amphitheater, uniformed officials, folk dancers, and a crowd watching. I could not approach, so said the guards, but I followed the path up and around to the highest point. What was left of the Inca construction was very impressive, an artistic form of fitted stone blended into the hillside. Like the woven cane panels, this work too was purely functional and all the more beautiful for it. Stones were fitted in their natural shapes to use the most material possible from each, rather than squaring the blocks wastefully. The work was exquisite and I wondered how it had been completed without iron tools. Great blocks, some the size of dining tables, were shaped to fit so closely that a knife blade could not be inserted at any part of the joint. This would not be difficult if the block was squared, but the stones were irregular and must have been shaved, filed, and painstakingly aligned one at a time. Even foundations of buildings were done in this style and indeed it is superior, for they still stand tight and strong after many centuries of earthquakes and weathering.

A little boy with a bird sitting on his head asked if I wanted to take a photo of him, but I declined. I shy away from such posed photography. There were no other tourists about. I sat on a rock for a bit, enjoying the view of the city and the brown hills beyond and the bold blue sky with white clouds. Continuing along a footpath I came upon a young boy about 10 years old wanting a dollar for his collection of currency. It was a tactic I was to hear often; there are of course plenty of dollars in circulation and if he got one, it would surely be converted to candy or ice cream immediately. Seeking water, I hurried down a path that would take me back to the city. At a gate station I inquired about the path down and after replying, the woman asked me if I had a tourist ticket. Obviously, I'd come in by a different way and so hadn't passed the gate. "What ticket?" I stalled, vaguely recalling that many sites about the city charged admission covered by a single ticket I could purchase at many locations in the city. I turned but did not stop walking, and mutually confused we parted. Farther down the path I climbed a few steps onto the ruins to take a photo and out of the corner of my eye saw a security guard notice and start my way. This side of the rocks sure was better guarded! I wondered what sort of permissions the throngs of people milling about above me on the ruins had been given. Continuing on down the tourist path I passed people from all over the world talking in their various languages and slowly making their way up the steep cobblestone path. At a road crossing we were held back by guards as vehicles sped past, lumbering sport vehicles with dark windows and pickup trucks with business-suited politicians waving from the back. People called "the president! did you see the president!" but I was unsure of whether they were affirming or asking whether Toledo had just passed us in a truck. I was shortly in the lovely alleys of the tourist district, where shops and hostels and restaurants abounded.

I was craving pizza. I am ashamed to admit it, but once in a city where I could buy a proper Peruano meal at a restaurant all I wanted was pizza and a lemonade. Apparently I was a typical tourist in that respect, for pizza joints abounded. I happened to pick one of the more expensive ones this first time, but the food and the lemonade were absolutely amazing at least to my starved tastes. And regarding Peruano cuisine: I spent the entire trip searching for the world-famous menus and finally concluded that the diverse combinations of seafood and mountain meats and potatoes and tropical fruits were for the enjoyment of the high classes only, not something I'd find on the streets. I ate my pizza and looked out at the plaza shining brightly in the afternoon sun. Tourists trudged past, tailed by shoeshine boys and postcard sellers and the occasional old woman in a bowler hat with a blanket shawl full of goods for sale. It felt good to be on the ground among the people. On the bus I had felt as if I was high upon a throne, peering down from the upholstered upper deck upon a land I could not hear nor smell nor touch nor stop to look closer at. Most visitors in the plaza did not carry packs, probably having left them at their hostels, and I decided I would do the same upon finishing my meal. I was traveling light but the tent and the sleeping bag took up so much space that I always had to carry a bulky bundle that screamed "rich gringo" wherever I took it. In Peru the people used the term "gringo" and it carried a negative connotation to me, dripping with envy and desire for all that I represented. I was reluctant to admit that though I was rather far from fulfilling the stereotype, I had much more than they did and could get almost anything I wanted back in the States. The feeling that I didn't belong was nearly enough to make me want to go home.

I didn't go home, but I moved on. I wasn't intending to blend in. My intent was to make a transect of sorts, watching and listening and hoping to come upon a handful of beautiful places before I winged my way home with a sketch book full of lessons to share. I paid for my meal and went searching for a hostel. Throughout the backpacker district, single room with a bath ran s/20, a double s/28, and without a private bath s/15. Other cities, I would find, charged per person so it was no more economical to travel in couples. I got a room next to the train station so I could easily catch the 6am train the next morning, left my pack in the room, and went out again to browse shops and watch people. For 1 sole (28 cents $US) I could buy 30 minutes of internet, a small ice cream cone, 5 big oranges, or most of a meal in the markets. I allowed myself some selfish satisfaction in my choice of destination; had I gone to Europe I would be living on bread and water for twice the cost. There were surprisingly few Americans in town but many English, a few Germans, and many Spanish-speaking tourists presumably from elsewhere on the continent. I located the artisans' market and looked at the crafts for sale. There were exquisite textiles, carved stone, gourds etched with beautiful designs, and painted pictures. Vendors pushed their goods with such urgency that it disgusted me. "Sweaters!" they whispered. "Mister, sweaters! Hats! Gloves! Ponchos!" They spoke while gesturing excitedly and thrusting the items toward me as if I was unaware of what lay under my nose. Outside a presidential convention meeting was spilling out of a building into ready vehicles at the curb. A band played and people looked on from behind a perimeter set by scores of kevlar-clad police. They stood in neat lines arm to arm and broke with an efficient sweep as the pickup trucks roared off through the narrow streets with irresponsible haste.

Traffic was different in every city I visited, uniquely suited to the geography and the streets and the road access to the city. In Cuzco the taxis were tiny, boxy Korean Daewoo Tico sedans with four doors where only two should fit. They buzzed over the cobblestone streets and squealed around corners with the fluid smoothness that only such tiny cars could have achieved. Also there were larger Toyota station wagons and an assortment of 4WD trucks and utility vehicles purchased by well-to-do businessmen for the rough roads of Peru. There were stoplights at intersections and though constantly stopping and going, traffic somehow managed to speed past more rapidly than I thought safe. Carefully I made my way to the city markets, surrounding the train station and nearly devoid of tourists. Prices there were much better than in the artisans' markets and also there were common goods for sale. One could buy shoes or shirts or soap or tools. The food markets were the best I saw anywhere in my travels. There were distinct class levels: The top tier sold from tiled counters under a corrugated roof enclosure that also housed the chocolate market, the fruit smoothie booths, the cafeteria section, and sellers of fashionable clothing and music cds and electronic devices. Then there were the street markets where people sold fruits and meats and fish and vegetables and coca leaves and cooked foods and breads from carts and tables under tarpaulin sunshades. Scattered among these booths were the lowest class vendors, women in bowler hats and braids who sat on the ground, their skirts drawn about them, a few goods laid on a sheet at their feet. Prices corresponded to these class levels and so I usually bought from the sidewalk sellers. The markets fascinated me. There were heaps of plucked chickens with heads and feet sticking up in the air at strange angles. Racks of sheep heads blackened in the cool air grinned devilishly. Potatoes of more shapes and colors than I ever imagined lay in heaps. There were eggs and chilis and olives and mountains of grapes. I saw bananas, papayas the size of basketballs, kiwifruit, clementine and navel oranges, apples, cheeses, corn. The corn was blue and red and yellow and white. The kernels of the white and yellow corn were each the size of lima beans, in irregular bulging rows on the ears. When popped they are sweet and soft and spherical. Tomatoes and spices and sauces were for sale. I particularly like walking through the spice markets wherever I travel, for they smell wonderful. It was growing dark and the vendors were packing up and trying to make some final sales. As I passed her stall, a woman seized a pasty white pork shoulder and thrust it at me, hoping that perhaps this neatly dressed visitor in a blue button-down shirt, khaki pants, and flip-flop sandals would have a use for a gnarly mass of raw pig.

There was so much food for sale in the markets. In the States, grocers put false bottoms in their barrels and make stepped shelves for their fruits to make it look as if there is a rich abundance for sale. In Peru, one of the poorest countries of South America, many vendors carried hundreds of pounds to and from the markets every day. There was so much for sale that each seller sold little and so lived in poverty if not in hunger, and most of that food must have gone to waste. It is unfortunate that most cannot be exported due to the lack of pest and disease controls, which would be prohibitively costly to develop. In the deepening evening shadows I peered into booths trying to discern the salesperson within. Nearly buried in a small hole among the shoes or the sweaters or the potatoes old women were eating from enamel bowls of potato soup with shreds of meat and crusty dry bread. I searched for places where the fruits and vegetables for sale might be prepared and served but always the menus were the same: fried meat, boiled rice, fried potatoes, fried fish, bread, sauce, soup. There were no marinara sauces or steamed vegetables over rice, no fruit bowls or mashed potatoes. The people of the central Andes quietly sold their great diversity of foods to those who would buy them and contented themselves with traditional fare.

Back at my room I took out my water purifier intending to pump some tap water and refill my water bottles, and as always after traveling or long storage I first tested it with dye. It was a new cartridge but an older model that has been on the shelf for a long time, and it didn't take out the dye. Maybe it was a different model of filter, I thought. Or maybe it was cracked, dropped at some point in the local sports outfitter where I bought it. I discarded the cartridge and wondered how I'd fare buying bottled water for the rest of the trip. It was certainly inexpensive to do so, but not convenient to fit the various sizes of bottles into my pack. I wondered how clean the tap water was in the mountains - it must be better than in the desert shantytowns outside Lima where cholera epidemics periodically run rampant, but so early in my trip I was not about to try my luck resisting new microbes. It was dark outside my window and I could think of no place I really wanted to go. With all the tourists the bars and discos were sure to be packed but I had a 6am train to catch and needed more rest to recover from my long bus journey. I washed up, drew back the coarse blankets covering the squeaking mattress, and gathered them around my feet to ward off the chill as I wrote in my journal.

Pondering the similarities and differences of the places I'd visited, I wondered about where I fit into it all. "There is so much I can learn here," I wrote, "but I am afraid that no matter how long I stay or how far I search for an understanding of the place, my conclusion will be that I do not belong and so cannot understand. I should not travel to find a place for myself and others should not model their own lives on my people and their Western culture. Quality of life cannot be compared on equal terms between different groups and one cannot gain what another has by dressing and singing and behaving like them. We each have special ways of life and we should refine them, not go elsewhere seeking something better." I liked my idyllic solution to all of man's woes, and it seemed for a moment to be a significant lesson. But I thought a moment more and remembered the faces on the street turning to watch me pass, the eyes bright with envy. I continued to write, "Greed and envy would never let the matter be as simple as that. Maybe I can find a middle path." There it was, an incredibly arrogant statement followed by an admission that it was unachievable and foolish. I was right back where I started, aware of the divisions of class and opportunity that my presence brought to attention but unable to think of a way to remedy the situation. All I could do was step carefully and listen closely and hope that answers would emerge from my experiences.

Since the winter solstice was approaching the daylight hours were few and it became dark early in the evening. It seemed too early to retire so I ventured out into the markets with the hope that I might see something special or memorable. There were no tourists at all in the back alleys of the street markets, down the hill a ways from the train station, and the sharp glances and suspicious looks of the people told me that this was usually the case. It takes some courage, I suppose, especially at dusk. Feeling somewhat unsafe myself I made my way back to the main street, but I made the mistake of passing though the meat market as they were hosing down the counters. Stepping carefully I tried to avoid the repulsive puddles but still my toes were splashed again and again. I reassured myself that it really couldn't hurt me and hurried on. Back in the well-lit plazas there were many people about but not feeling drawn to any of the social scenes that evening I decided to catch some rest before the next bout of traveling.

The hard mattress, flickering lights outside, and anxiety about waking in time for the train together ensured that I did not sleep well. My shower water was just a bit above cold so I splashed some water on my face and gathered my belongings together. It was still dark outside when I woke and very quiet. Like Lima, Cuzco slept at night. There were no horns, no barking dogs, and little traffic in the early hours of the morning. I was early at the station and chose a window seat on the plain backpacker train that would stop at many points along the way to drop off Inca Trail hikers. I had my pack with me so I could stay the night in Aguas Calientes if I so chose, but I would not be hiking in. Regulations required the purchase of a guide to place a limit on the number of people allowed on the trail and to help protect the natural environment. This was costly and I'd heard that the 600 people who walked the well-built path daily made it closer resemble a city sidewalk than a mountain trail. The train seats were in opposed rows that puts passengers gazing into the eyes of strangers for the duration of the trip. A large woman took the seat beside me, immediately making me wish I'd arrived later and chosen my own seat partner. Then a couple with a small child took the opposing pair of seats and for a moment I entertained the hope that the child would take the seat opposite me, giving me some leg room, but the kid migrated from parent to parent to the aisle and other friends in the car and I was trapped in my very small corner.

The couple lived in Stockholm; he was Peruano and she was Swedish and they'd met in Sweden. It was her first time in the country and she said she was enjoying very much the experience of seeing her husband's home and the places she had heard him talk about. The large woman next to me was a self-described cynic. "Lake Titicaca was awful," she said. "We took a boat out to the floating reed islands and they were wet and mushy and I really didn't find them enjoyable at all." Across the aisle, a group of English men took seats. A woman from Boston had arrived first and sat rigidly with her handbag on her lap, staring silently at the empty seat opposite her. The four men debated for a minute how to seat themselves; they proposed that if the woman from Boston moved up and across one row they could be seated together. Still staring blankly, she replied "won't you be close enough?" It could have ended there, but there was some muttering among the men as they settled into their seats and she retorted with a wisecrack, "Gosh, you act like children." A polite protest ensued, ending with raised words "Why do you have to act like that? I was beginning to like you!" in crisp British speech. It could be a very long trip, I thought. I didn't know how long it would be, so I asked the woman next to me. "Four hours," she said. "You sound like a pretty active guy. Do you think you can last four hours sitting still?" she asked. I casually brushed off the hardship and wondered to myself how she could overlook the fact that my traveling was almost entirely comprised of sitting still.

The conductors kept to rigid rules and at the appointed time the doors were closed. Latecomers pressed their faces to the glass and pleaded for admission, but none were allowed to pass. Bells were rung and we were shortly on our way, creeping out of the station and through frosty alleys. We stopped and then reversed direction, climbing a steep zigzag track. A switchman stood at each corner with a big iron wrench to shift the tracks so the short train could climb higher. Stray dogs scampered through the alleys beside the tracks and children stopped playing to look up at us, covering their ears with their hands to muffle the screeching of the wheels and smiling up at the strange faces flashing past. The cynic and the woman from Boston had struck up conversation. "I am thinking of going to Manu," said the Boston traveler. She was in her 40s, wore a worn green knot hat, and spoke slowly and hesitantly as if she was confused to be awake so early and not sure where she was going. "I hated Manu," said the cynic. "You shouldn't trust my opinion though. It was hot and sticky and there were bugs and we didn't see animals. I only wanted to see the giant otters - that's what I went for - and we didn't see any. You might like it though. A lot of people go there." I asked her about the weather, the forest, and the insects. It didn't sound bad at all. She thought my plan to take a truck to Puerto Maldonado sounded like quite an adventure but she made no comments against it. I'd passed that test!

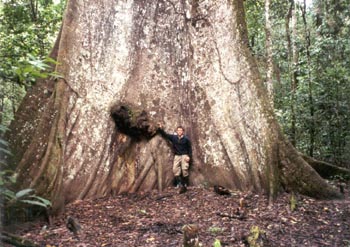

The man took his little boy up and down the aisle or sat on the armrest of his chair, the little boy playing in the seat, and I felt sorry for him having the seat across from the large woman, which effectively meant that he could not sit. There was so little leg room. I watched high farming valleys slide past my windows, heavily frosted in the shadows. Tooth-like snowy peaks poked over distant hills. In courtyards and enclosures made of sod, corncobs lay drying in the sun, yellow and reddish purple ears carpeting the ground. The rainy season had recently ended and the season was the coldest of the year, so harvests had recently been gathered. Cattle cropped dry brown grass near villages and in the empty spaces herds of llamas grazed on coarse yellow tufts of grass. The train was descending, following a valley toward the great forest of the Amazon basin. La selva, the forest was called in Spanish, one word to describe the vast untamed wilderness that covered much of Peru and points east. In the States we have pine breaks and mature hardwood stands and birch forests and alpine conifers and mixed temperate woodlands, but in Peru there was only la selva. This simplicity had the flavor of a wild and exotic place not yet broken by the activities of man. I was soon to see myself how thoroughly men had slashed into the forests, but still the great expanse of wet green jungle eroded my confidence and left me feeling powerless and small.

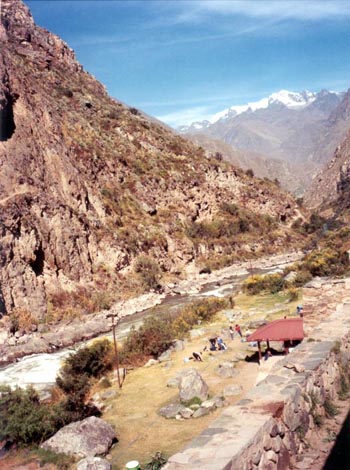

The train was passing beside a fast-flowing river, the Urubamba, running clear and swift over tumbled granite boulders. Enough rain fell at those altitudes to erode the Andean plateau into spectacularly steep ravines and canyons. Snow shimmered on glaciated peaks high above. We stopped at numerous junctions with the Inca trail, letting off young backpackers from all over the world. The pretty girls I'd never had a chance to talk to departed, but the large woman beside me stayed and so did the Swedish couple with their restless child. The Swedish woman was explaining, "I asked him what his favorite food was, what he would have if, say, for his birthday he could have something special here in Peru. Cuy, he said, and his eyes lit up. One all to myself." They were speaking of guinea pig, a delicacy of the mountains, cute chubby furry rodents that were scooped up from the kitchen floor, butchered, cleaned, fried in hot oil, and laid spread-eagled on a bed of rice garnished with steamed vegetables. People said the meat was passable but not fine and often I heard it described as "a greasy bag of bones." Since the meal was not an everyday dinner most places selling it were tourist dives with prices to match and I never did eat any. We were in the high rainforest now. It was hot and steamy and plants with large leaves and brilliant flowers crept close to the tracks. Vines hung from tall hardwoods that had a distinct tropical appearance so different from the hardy maples and oaks from home that shed their leaves every winter to wait out the snows. These tropical trees were softer, gentler, weaker, and more elegant, with smooth pale bark and few branches and large leaves. Colorful birds and butterflies flitted about in the sunshine. It was peaceful and I was content to wait out the journey.

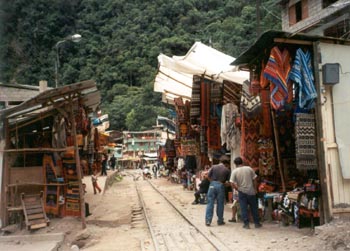

Aguas Calientes arrived rather suddenly. The train went on but everyone got off, all on their way to Machu Picchu. The little town existed solely for tourism and both sides of the train tracks were lined with colorful shops selling everything that could be found in Cuzco but at prices two to four times higher. I walked to the end of the restaurant strip and then selected a sandwich shop, where I ate a disappointing meal. A very tough and stringy fillet of beef or similar meat had been dropped in oil, then laid on a stale roll with cheese and avocado and tomato and salt. I wondered, "Why couldn't these people grill their steaks?" There was so much potential for a good meal but when I bit into the sandwich the tough greasy meat slid out and I wolfed it down in one hungry unappetizing indestructible mouthful. Fed, though not satisfied, I paid for my food and wandered back across the tiny town to where buses left for the ruins high above. While I ate another train had arrived with mostly Latin-looking visitors who now formed a line hundreds of people long waiting for bus departures. Already disgusted with the cost of visiting this attraction compared with the cost of the rest of Peru, I turned around and began walking. The train tracks and footpaths were the only way into the valley, but here a road ran back up to higher villages and a hydroelectric plant serving the tourist area. I followed it in the opposite direction, cutting past a recent rockslide, through a cliff face blasted out to make room for a single lane, and across a rusted iron bridge over the river. The road continued downriver, a washboarded clay track running parallel to the railroad. A short way out of town I passes a group of men burning plastic bags of trash on the roadside beside the clear waters of the river, the filthy destination of hotel wastebaskets and municipal trash collection. Farther on men broke granite with heavy hammers, working from slabs recently tumbled down in rockslides and filling wheelbarrows. They wheeled loads of football-sized rocks up a ramp and dumped them into a rock crusher driven by a sputtering 2-cylinder engine. Crushed rock flowed onto a growing heap, destined for the road on which I walked. It is a constant battle against nature to keep a passage open there in the steep, wet, rainy forest.

The temperature was in the 90s, I guessed, and I had not packed nearly enough water for the hike up and back. A dirt access road snaked its way up the steep mountainside through countless switchbacks, but the footpath went more directly. Not knowing the way, I was about to take the road when a man a hundred meters back across the river shouted and motioned with his arms that I should take the rocky rutted path to the right instead. I smiled and waved, surprised at his interest in me and grateful that I was not being called back for violating some rule. The path intersected the road many times and there were several wooden signs showing the distance completed and remaining. It was discouraging at first but then there were no signs for a while and the next showed great progress. Climbing quickly, I soon had a spectacular view of the rugged, forested spires of rock with sheer cliffs and unbelievable steep sides. Bees buzzed among flowers that cascaded down the slope. Sweat dripped off my body and I took off my shirt, not knowing when I could wash it again. A helicopter took off from a grassy pad below and sped off down the valley, ferrying well-to-do tourists from Peru's most famous attraction. It is not often that I see helicopters from above; always that happens when I am climbing in the mountains. My pack was very heavy and I wondered again why I was carrying a tent and sleeping bag when hostels were so numerous and affordable. Rounding final switchbacks, I glimpsed buildings and a parking lot and stopped to put on my shirt, not wanting to strut out sweaty and half-naked into a crowded lot of prim and proper tourists sipping drinks at the cafe and reserving their rooms at the $400 per night luxury hotel perched beside the ruins.

There was a $20 fee to enter and I had to check my pack. After carrying it about two thousand feet up the mountain this was a great disappointment to me, but the reason was clear though not listed: the park service did not want people camping among the ruins, or carrying in anything that could be left as trash. Food and beverages were not permitted. I had contemplated walking off into the forest and camping for the night, and I credited them for being one step ahead of me. Taking some film and my camera and drinking what little remained of my water, I apprehensively handed my pack to the sleepy guard at the check station and passed through the gate. People were coming out carrying day packs and I instantly wished I'd taken my pack hood with some food and water and my journal. There were signs guiding the approach but somehow I lost them while seeking a way that would give me the much-photographed overlook of Machu Picchu. I walked ever higher on an overgrown trail into the forest until I met a boy about my age coming down. "Do you have any idea where the Agricultural is?" he asked, looking for the terraced gardens that fed the mountain city. "No," I replied. "Does this trail go anywhere?" "It just keeps going up into the hills but there is a nice overlook not too far up," he said. He went down and I continued up, looking for the overlook but never finding it. I turned back and cut across a terrace to a footpath, feeling guilty that if everyone did that there would be ugly brown tracks crisscrossing the beautiful green terraces. After climbing down a few walls on the ingenious steps the Incas had built - long stones protruding from the walls to make diagonal stairs at just the right spacing, open and airy and exciting - I was at the high altar overlooking the ruined city. A great boulder had been flattened and carved with a high knob at one side and small steps leading up to the flat. I imagined goats being hauled up by ropes about their horns and slaughtered in sacrifice, the blood running down the stone in scarlet rivulets. But later, reading a brochure, I saw the stone described as an astronomical monument. I am still not convinced.

There were surprisingly few people on the grassy terraces below. The view was lovely, looking just like all the postcards and book spreads, but I was nervous about reclaiming my pack and eager to see the ruins up close so I scampered down the packed dirt paths, slowing to pick my way down stair-step stones where I could find a shorter way by doing so. I came upon several guided tours, the leaders speaking in Spanish, and threaded my way through the milling schoolchildren and camera-toting tourists. Actually I was one myself, but moving quickly. Curiously I explored every path I came to, once taking a narrow set of stone stairs straight down the slope to where they ended at a vertical drop many meters into a steep brush covered slope. Nearby there were tilt gauges set in concrete in the sod atop a terrace that appeared to be creeping and spilling into the valley. The gauges, short posts perhaps 30 centimeters tall each fitted with an angular scale against which a weighted wire hung plumb, were cocked at odd unnatural angles that showed just how rapidly the ancient city was going downhill. Some scientists speculated that a single slump of the hillside might soon occur and level most of Peru's most popular tourist attraction. Looking out across the stone walls that had stood more than six hundred years it was difficult to imagine them not lasting hundreds more, but I knew from looking closely that many walls had been restored. There were few loose stones lying about and every wall was topped off to the ridgelines. Other walls were so finely built of roughly squared blocks that I knew at first glance they had not shifted at all since an Inca stoneworker wrestled them into place.

The sky was overcast with wispy clouds obscuring the taller peaks nearby. Enough sunlight penetrated the gray to brighten the landscape and make it very warm so that soon I was wishing I had brought water with me. I scampered around the cropped green terraces, noting that the turf was kept so neat by a herd of resident llamas munching indifferent to the camera-eyed tourists positioned around them like snipers. Seeing a ladder protruding from a hole in a boulder pile I hurried off the path to investigate, expecting at any moment to be called back by a park official, but the cavern was empty and shallow and I wondered why people were working there. The tumbled boulders were overgrown with vines and shrubs, covered in loam, and riddled with slippery holes where one might fall in among the ants and become stuck. I wondered how on earth the Inca builders had prepared such a site for this fine palace. Continuing on toward the distinctive peak that is the backdrop for the traveler's memory of Machu Picchu, I moved close enough to see people climbing up the steps that led to its summit. As I approached the base the peak looked closer and less lofty and in my thirsty haste I decided it wasn't worth clambering up, though now I wonder why I didn't take another hour to see all there was to see. I had seen eerie photos of the ruins perched atop misty mountains and read the fascinating history of the mountaintop retreat of the Incas, how the Spanish never sacked the remote and hidden city, and how the site was reclaimed from the jungle in 1911 after Hiram Bingham was led there by a local farmer. Standing there among the great stones I thought the place looked exactly like the photographs but that the romantic mystery surrounding it had eluded my visit. If one arrived in a rainstorm, coming by the mountain path with close companions who had shared the hardships and the anticipation, and saw with a blast of wind the ancient city freed from the mist and lit by a ray of sun slicing through the clouds, then one would have captured the essence of the place. I had failed to do so but had seen what I came for; those moments of perfectly balanced earth and water and light are very rare and are not to be expected. Turning around I took a different way back through the ruins.

A mountain stream had been channeled into the city and cascaded through a series of carved stone basins, each with finely built culverts and drains and troughs, abetting my curiosity of how such a remote place sustained itself. Every new view of the incredibly steep landscape and the enduring stone monument upon it caught my attention. I took more photos than I expected and when I developed them I found that all turned out well in the bright but muted sunlight, so my album has many pages of Machu Picchu. I took a long last look at one of the world's most famous archaeological sites and then ducked around a corner and followed the path back to the modern world urgently pressing at the gate with its buses and a fine hotel and a hamburger stand and well-dressed people chatting in many languages. The guard at the baggage check was sleeping; I could see his feet protruding from around a corner on one of the bunks where packs were stowed. I thought of simply taking my pack and leaving, but instead roused him with several loud greetings and exchanged my numbered paper ticket for my thankfully undisturbed pack. Most of it was replaceable, but my journal and films were not and I guarded them closely for the entire trip. Very thirsty, I bought a small bottle of water at 10 times the cost of the same in the Cuzco markets and hurried down the path, convinced that I must catch the train back to the city rather than pay the high prices of Aguas Calientes. In hindsight I would rather have lingered and mingled with the tourists, for I found few companions in my travels thereafter. The walk down was more pleasant and short, so soon I was back on the dusty road beside the river. Buses lumbered past and the rock crushers were still at work but the trash burners had departed and the stinking fire was out.

In town I raced about looking for a place to buy a ticket home. Among the disorderly shops there were many agents selling hotels and tours but all sent me elsewhere for a train ticket. At last I arrived at the correct ticket window and was quoted a fare four times the rate I'd paid to get in. A round trip ticket bought in Cuzco would be simply twice my low fare, but as the rail link was the only way out besides footpaths the operators were free to collect from trail hikers and unwitting travelers such as myself. It was no place to bargain nor was there time, so to complete my $70 day (the most expensive of the trip) I purchased a ticket to Cuzco on the Vistadonne, the upscale tourist train. There were no overhead racks, only lovely curved glass windows suitable for looking up at the snowy peaks nearly directly above the train, and though many backpackers were aboard who had, like myself, missed the backpacker train there were considerably more affluent tourists than there had been that morning. They were middle-aged couples and friends with pressed trousers and handbags and collared shirts, toting video cameras and guidebooks and in my opinion remaining aloof and unaware, perhaps intentionally, of so much that was happening around them. The lady across from me said I was lucky to be traveling alone as I had no one to impress and no one to wait for. I still looked great though, she said, no one to impress but I still impressed. In my wrinkled blue second-hand button-down shirt that was a size too big I felt undeserving but appreciative. I was just trying to look respectable since I was a guest in the country. Behind me a couple from England traded stories with the people sitting across from them. "We brought so much luggage," the lady in heavy looking glasses said. "The water suitcase was so heavy that we had to pay extra at the airport." They had brought 40 pounds of water from home, untrusting of the less costly and more convenient Peruano brands. I tucked my head into the space between seat and window and tried not to hear her drone on and on about the exotic wonders they'd seen. The shallowness of her understanding disgusted me, but knowing that I also was an ignorant visitor I kept quiet and watched the evening shadows swallow the hills outside.

At the Ollantayambo station, 45 minutes by train from Cuzco, the conductor announced that those who wished could depart and take the waiting buses to the Plaza in 10 minutes for 5 soles. Most people left, debating back and forth the equivalent costs. "We can all go back for six dollars," a girl said. "Only six dollars. Let's go!" And so they did, trooping out and leaving a handful of unhurried travelers behind. Those 5 soles, a dollar and a half, were for my dinner and I had no plans to go out afterward. We zigzagged our way down into the city, switchmen changing the tracks as we passed, and at last I was on familiar streets. I sent some emails home, noticing that the cafes were very crowded in the evenings. Young people emerged from dilapidated buildings wearing neat and stylish clothes fit for any city. Moving on I searched for affordable food to balance my expensive day. Later, I wrote: "I feel much redeemed, though not completely. I'm still learning about this country. Got a huge bowl of noodle soup and a big plate of spaghetti with a light tomato-meat sauce for s/3." It was at a hole-in-the-wall cafe, the menu smudged on a chalkboard, a few people inside. The manager shuffled over to me as I took a seat and took my order. The soup was good and the spaghetti, though the pasta was overcooked and the sauce was pale and oily, was passable. I silently lamented how so many fine tomatoes and peppers and onions and spices and good cuts of beef were spoiling in the markets because no one knew how to cook them properly. But recommending change to the food preferences of a culture is no business of anyone. Happily fed I set out to find myself a place to stay.

For s/20 I got 2 twin beds with a shared bath. The door had a flimsy latch and I was given a small padlock and key which I was sure would be a small deterrent but by no means secure. The beds seemed comfortable enough and the proprietor arrived shortly with a towel and a bar of soap, an unexpected luxury. It helps so much not to travel with a wet towel in one's pack. I sank into the bed thankfully, marveling at how lovely Peru was. On the train that morning people were talking about how clean the country was. People dressed well, restaurants were clean, and vendors on the street were very careful to use good hygiene. "I think it is wise to buy from vendors early in the day," I wrote, "rather than later when the dust and spills have accumulated, but I've not been sick at all yet." My luck had run out, and two hours later I was afflicted with the traveler's nightmare of food poisoning. It might have been from the meat sauce, lurking in its semi-warm pot for hours before my arrival. Miserable, I lost my affordable dinner and most of my water and huddled in my bed, hoping to catch some rest between waves of nausea and hurried retreats to the washroom. As in most mountain towns in Peru there were no toilet seats, perhaps to eliminate the need to clean them or because such an expense was deemed unnecessary, but adding to the misery of food poisoning. My nose started bleeding amid being sick, completing my new understanding of what six more lonely weeks were going to be like.

Dawn found me shivering under the thin blankets. The shower water was cold and I could only splash water on my face. I ate half an orange but it didn't stay down, and even water made me queasy. I would done anything for a travel companion to look after me then, but of course I'd arrived alone. Most young backpackers were traveling in couples, so being solo I was not wanted for more than a conversation in passing. Those who traveled in small groups seemed quite content with their small groups and wanted no newcomers, at least not a scruffy single guy with a big pack. Invariably we were going in different directions. I was going to Puerto Maldonado, by road, and no one else even knew that was possible. I had doubts myself, and so after resting a while longer I packed my belongings, paid for my stay, and took a taxi to the Plaza Tupac Amaru where I'd read in a guidebook that trucks left for Puerto Maldonado. I was looking for a camion grande, a large petrol truck, short and stocky like a construction dump truck but with a cylindrical tank on the back. The top third of the tank would be flattened and short railings would be installed to form a cargo area used to haul lumber or produce out of the rainforest on the return trip. People also rode atop the load in both directions. But there were none of these trucks in sight as I stood on the curbside in the hot sun. Across the plaza a crowd of youths was rallying, probably for the same cause of previous protests. I walked to several smaller trucks and asked the drivers where I could find a truck to Puerto Maldonado. It seemed that many had no idea where the place was; they knew their mountain home and no other. Finally one man sent me off to a place where I could find a truck, several blocks away. I soon became lost and unsure of where he meant, so I asked a pair of taxi drivers who hoped to secure my business. They did not immediately recognize the city name so I began naming intermediate towns. "You can take the bus to Urcos for 5 soles," one driver said. "There is a bus from there to Puerto Maldonado, 50 soles." I was surprised to hear this as every guidebook and internet reference I'd found said no buses ran the route, considered one of the worst roads in Peru between two locations of significant interest. "I can take you to Urcos for 50 soles," he said. For a little less than 15 dollars, I could be on my way. I was still sick and I'd seen the buses running to Urcos - little Toyota vans with sliding doors packed full of people. I wondered where my pack would go. I needed to get to Puerto Maldonado and I'd read that the trip could take as much as 10 days in bad weather. "Take me to Urcos," I said, "50 soles." I had just enough soles for the fare and a bus ticket.

It was well that I took the taxi. I leaned forward from the back seat to hear the driver pointing out the penitentiary and pre-Inca ruins and various restaurants where certain local specialties were served. 30 minutes into the 40 minute ride we came upon stopped traffic and scattered rocks and cactus paddles in the road. "What happened?" I asked. "Was there an accident?" He didn't know, and sped through the confused knot of vehicles until we could go no farther. Vans loaded with rafts and full of tourists were mired beside the local buses and taxis and trucks and personal vehicles. The driver spoke with several people, then turned to me. "There is a problem. The strikers have blocked the road. It is like this all the way to Urcos." I asked how far, and he said "it is not far. Six, seven kilometers. Yes, you could walk." He accompanied me a short way ahead on foot, hoping that there might be some way to get his car around, but I took my pack expecting a change of plans at any moment. The scattered boulders became thicker and we approached a small crowd of protesters, perhaps a hundred people, holding a long pole across the road and waving a banner with a message I did not notice. Behind them palm stumps smoldered in the street and more stones, tons of them, covered the pavement as far as I could see. People were walking calmly past and the protesters milled about quietly. There were no police in sight. "It will be open later," my driver said. I asked how much I owed him and for 40 soles we parted, he returning to Cuzco and I walking ahead into an unknown place.

Feeling exhilarated by the faint hint of danger and the uncertainty ahead, I shouldered my pack and hurried past the roadblock. Farther on a crew was repairing asphalt where a fire had burned through it. They had an iron sheet set on blocks over a wood fire for heating asphalt. In places the rocks were very closely packed and there were so many that I wondered where they had come from. The farmers were also on strike and only they had the equipment to load and deliver these hundreds of tons of stones. I passed businessmen and women walking on the roadside, and others passed me. The sun was intense and I had little water. I put on my hat to keep from being burned, shifted my pack, and plodded onward. The road wound through a small valley of pastureland and harvested cornfields and scattered buildings and ahead beyond a hill I could see what must be the outskirts of Urcos. I took up conversation with a man who was carrying a bright red down jacket under his arm. His name was Juerge and he was going to Ccataca where, I gathered, he lived and was studying to become a mountain guide in the nearby high peaks. It was cold up there, hence the heavy jacket. He told me that the buildings ahead were indeed Urcos and that the bus would take me that day to Puerto Maldonado. Trucks also left frequently, but while the bus took one day the trucks took two to make the trip. Juerge flagged down a car, somehow, since everyone was soliciting rides from the few cars that had become trapped between thickly stoned sections of road and made their way back and forth, dodging boulders and often clattering over small stones.

We squeezed into the four door sedan, then stopped to take in more people. A man took my pack and put it in the trunk, where a boy of about nine also sat and held down the lid to keep it from bouncing and knocking him in the head. Though I tried to quiet my mistrustful suspicions, I kept peering back through the tiny crack at the trunk hinge imagining the boy rooting through my pack and stowing my valuable possessions in dark recesses of the trunk. The boy was in the trunk because there were nine people, including me and the driver, in the seats. We started driving back the way I had been walking and I, alarmed, asked Juerge why we were going back. We needed to drop the boy off at the school, he said, which made no sense to me since I thought the teachers were striking. Again I quieted my suspicions and presently we let off the boy and turned about to weave among the boulders in the other direction. Eventually the car could drive no further and we spilled out onto the road. I snatched my pack and Juerge indicated that I should pay the driver 50 cents, the same as he was going to. The driver lamented "Only 1 sole? but senor, there are many stones! It is bad for my car." One sole for the two of us, we stated, and went ahead on foot. We were closer to Urcos now and a bucked loader was on its way out to begin clearing the road. A small boy in his young teens was at the wheel of the giant machine, and he sped along over the rocks with the bucket high in the air. I wondered where he was going; by putting down the scoop he could have cleared a path in minutes.

The debris in the road thinned out as we entered town and the last thing I saw in the street was a large overturned dumpster. Juerge and I took a shortcut on a side street and were presently at the central plaza where a demonstration was taking place. Pointing to the bus parked there, Juerge said he would be back in a moment and hurried off somewhere. He would be going the rest of the way by taxi. I glanced around the crowded square. The demonstrators had megaphones and were reading speeches. Vendors sold food, people lounged in the shade of storefronts, and nowhere were there any foreigners even though I was on the main road to Puno. Evidently nobody else stopped in Urcos. I found a restroom and then approached the bus. It was a rugged vehicle with big knobby tires, a high ground clearance, and a roof rack that was already filling with burlap bags and tied bundles. A man handed me a clipboard with a passenger sign-up sheet and I selected a window seat near the back of the bus. I had only 49 soles in my wallet but they accepted this and waved me on. Later I found 150 more in my document pouch and was very grateful, as otherwise I would have been unable to change money until two days later and unable to buy food en route. It was noon and the bus would not leave until 4pm but I had nowhere to go and wanted to stow my pack under my seat for peace of mind, before the bus became packed, so I clambered on. There were dented overhead racks and every single seat was faded and torn and dirty. The floor was stained and dusty and I reluctantly shoved my pack under the seat, where it barely fit. Behind me there was a rear door through which sacks of potatoes were being loaded and packed in place, neatly securing my bag. I was quite uneasy about a night journey after reading so many warnings of tourists having their bags riffled through on night buses. There was one row of seats behind me and it was raised so more cargo could be put below. A rough hardwood plank formed a footrest. Already there was a sour smell in the air from rotting vegetables of past journeys that had never been washed away.

I still felt sick and had eaten nothing yet but I tried to fend off serious dehydration knowing throughout that I was about to sit on a bus for a day and a half with few breaks and no buddy to make sure I didn't get left behind at stops, so I had better moderate my beverage intake. Outside I watched petrol trucks come and go and I wondered if I should have tried to catch a ride on one first. Maybe on the way back, I told myself. I needed to make my boat up the Tambopata River in 6 days. Now, arriving by bus, I would be four days early in Puerto Maldonado. I had wanted to see the mountain passes by day, and to spend time in villages along the road, but I was sick and worried about more protests and not confident enough that I could arrive on time. At about 1pm the crowd marched out of the plaza in a long parade, carrying banners but walking silently. Women and girls called to our open windows hoping to sell corn and potatoes and chicken and chicharron, greasy fried pork gristle that I never found very appealing. I had only 20 and 50 sole notes and I didn't trust enough to hand them out windows and hope for change. Finally a woman came onto the bus selling ice cream for 50 cents and she said she could get me change. Having made more personal contact, I was reassured and soon she returned with my change. The ice cream tasted so good - cold, creamy, and sweet - and I felt no sicker eating it. It cheered me up that I was able to eat and get some sugar into my blood. More people had gotten on and the bus was filling up. A very wrinkled elderly man in tattered clothes sat in the aisle beside me on a wooden crate of rabbits. I wondered what people thought of me, an uncommon sight on their bus. I wondered if perhaps I should have bought the old man an ice cream too and I regretted not thinking of it sooner. With the language and culture barrier it is hard to make a friend without some such gesture.

The petrol trucks coming into Urcos were covered in dried tan mud and dust, a preview of the road ahead. Some were towing a tanker trailer though so I supposed the way must be clear to let such a long and heavy vehicle pass. I nibbled on an orange section timidly, wondering of my stomach would accept it and knowing that I needed food. I wanted more ice cream and vendors came through often selling helados and gelatinas and chicha and other foods but few passengers were buying and I did not want to appear any more rich and stuck-up than I did already, by looking different and carrying a pack. A little girl of about four years was clambering around the bus restlessly. She climbed onto the empty eat next to me and smiled. I smiled back, and she extended a finger and touched my arm. I could see the curiosity in her eyes - Why was I so light-skinned? Why had I more hair than the people she knew? She was probably returning home after a rare trip into the mountains and may never have seen a foreigner so close before. Angel was her name, she said. Later the seat was taken by a boy about my age wearing a white soccer jersey and carrying a small black book bag. Neither he nor anyone else nearby said much and we settled silently in our seats like passengers on an elevator, patiently waiting to arrive. At that point, actually, we were waiting to depart and the appointed hour had passed. Shadows were getting long in the plaza and the sunlight had taken on the rich colors of evening. Passengers began stomping loudly on the floor, slapping the side of the bus with a hand hanging out a window, and shouting "Vamos!" and "Hora!" No one seemed to care though. There was no business to nurture; the people had to get to Puerto Maldonado and there weren't many options for getting there. If the bus waited just a little longer they might gain another passenger and his fare, and so we lingered for more than an hour more.