North America's third highest peak rises dramatically eighteen thousand feet high above a flat brown plain.

A glacier covers the top of the steep volcanic cone. After a flight from New York and four hours travel by bus, Jeremy and Erin and I set out on foot to climb to the top.

to the index page

The Mexican volcano Citlaltepetl, often known by its Spanish name of Pico de Orizaba, is the third highest mountain in North America at approximately 18,400 feet. I'm not exact about that figure because nobody seems to agree how tall it is and estimates range by hundreds of feet. It is agreed upon that only Alaska's Denali and British Columbia's Logan surpass it in height, giving Cita claim to a respectable third-place title. The snow-capped volcanic cone rises out of a barren brown land southeast of Mexico City. Agricultural villages climb high on its slopes and, in 2002, no regulations of any sort existed to control access or climbing. The high base, accessible trailhead, and favorable weather patterns during the dry season make it an enjoyable climb that takes just a few days to complete. It was a perfect spring break destination.

The Newark airport is immense. One encounters giant blue "Are you lost" signs while circling about on narrow roads by the guidance of cleverly hidden signs that point in directions which no roads take. It seemed that half of the airport roadways were under construction. Jeremy and Erin and I had driven to New Jersey in Jeremy's Tercel, which was packed to the gills with climbing gear for three. The poor little car struggled to keep pace on the Interstate with no overdrive and more than 200,000 miles on the vehicle. In our haste we had neglected to bring pillows so the night seemed very long as we attempted to sleep in Economy Lot G. Jets roared overhead and we wriggled about uncomfortably between the gear shift stick and the steering wheel and the duffel bag full of axes and crampons in the back seat. Morning found us on an early flight to Mexico City, our baggage stowed neatly in the hold of a 737 that bucked and rolled like a seagull. I watched anxiously for Mexico while traversing the endless blue Gulf, but there was much more water than I was prepared to patiently cross. At last we made landfall, crossing over a layer of clouds below. Breaks in the cloud cover revealed a huge brown expanse that supposedly contained the largest city in the Western Hemisphere. The only sign of hills or mountains was the icy summit of Ixtaccihuatl rearing above the clouds, but that was enough to clear the sleep from our eyes. We had a mountain to climb! More hills rose out of the arid plain as we descended, and thousands of buildings materialized from the dust. They whirled and jerked about erratically as the bucking seagull caught gusts and overcompensated, and the ground became uncomfortably close without any sign of an airstrip. Then the plane leveled out and we glided in past a Wal-Mart store to a soft landing in Mexico.

In the airport we found a perfect rectangular nook in the corridor where we could explode our bags and stow our gear in backpacks and a small duffel bag. We purchased first class bus tickets to Puebla for 115 pesos each, at 9 pesos per US dollar, choosing to pay extra rather than brave the taxi system so early in our adventure. Looking back it would have been simple enough to take a 50-peso cab to the TAPO bus station and pay 65 pesos for bus fare. TAPO is the giant eastern bus terminal in Mexico City. There is a place to secure bags in lockers in the airport at Booth 10, but it cost 55 pesos per day, which is unreasonable for long trips. We saw secure storage racks at TAPO as well, but I did not inquire about the cost. It's always best to take what you can carry and no more.

During the two-hour ride to Puebla we observed that much of the countryside was on fire. The air was hazy and gray but not unpleasant, unlike the oppressive atmospheres of other cities I have traveled through. Perhaps we were timely with our arrival. The strangest thing about the fires was that nobody seemed to care. Flames flickered unattended among the pine trees in the highlands and the air in some places was heavy with dust and smoke. Flames licked at fence posts and utility poles beside the road at one point, but the traffic sped by without concern. The trees were not touched and the fires seemed to be quite docile. In the villages, people played football - soccer, to us gringos - and basketball in large open dirt arenas. Dome-topped Spanish churches dotted the countryside. After two hours on the neatly paved and painted express highways we emerged from thick forests in the highlands and descended to the city of Puebla at an altitude of 7000 feet. The toll booths and checkpoints were manned by green-uniformed, gun-toting Federales lurking behind walls of sandbags. From the small 1st class Estrella Roja bus terminal we took a taxi to the cavernous Puebla bus station. We purchased tickets to Tlachichuca for 41 pesos apiece at the AU counter and then waded through the crowds for half an hour before becoming enlightened to the fact that the AU bus to Tlachichuca left from the Valles terminal. Tlachichuca is a tiny town that many people had never heard of. I presume that many such towns exist however. Buses leave every 30-45 minutes but even so on a Saturday afternoon, the bus was packed so full soon after we got on that there was no standing room. Erin and I squeezed into one seat so a woman standing beside us could sit. Then we asked how long it would be to Tlachichuca: Dos horas! We traveled beside the high snowy peaks of Popo and Izta, tantalizingly close, and then left them for a huge dusty expanse dotted with occasional towns and cactus farms. The cacti have green paddles that are harvested and sold in the markets for food, their spines shaved off with a sharp knife. Paddles are harvested with thick gloves and cacti are planted in neat rows, individual paddles half buried in deep furrows so they may take root and grow.

In the towns we stopped to take on and let off passengers. Vendors walked through the bus and thrust trays toward open windows. The food looked delicious: sandwiches of avocado, cheese, and tomato on white deli rolls, cold drinks, fried potato chips, and other snacks. Our water bottles were stowed below and we were too timid to make a hurried purchase with our newly-changed large bills, so we merely watched. It was pleasantly warm but very dry. Our gesture of kindness in giving up a seat was returned when our neighbor produced a Coke from a bag she was carrying and gave it to us, having understood our keen interest in the drink vendor. Throughout our trip we encountered much kindness and no trouble of any kind. As the sun sank low over the hazy horizon we caught sight of the great cone of Citlaltepetl ahead. It looked immense, with concave sides rising in a perfect cone to a snowy summit more than ten thousand feet above us that glowed red in the low sun. We all felt suddenly unsure of what we were getting ourselves into. We were in a foreign country, in a remote town at dusk with limited language skills and no place to stay, hungry and tired, come to climb a giant mountain. Darkness fell as we disembarked in a dirt lot behind the Tlachichuca bus station, the end of the route. We gathered our bags nervously, relieved that none had been taken away at earlier stops, and wandered out into the town. Overhead, tattered blue and white banners strung between utility poles fluttered in the breeze. We made our way to the town square, which was quite empty except for a few taco stands and booths. Stray dogs scampered about in small groups and dry leaves tumbled along the cobblestones in a stiff cool breeze. The few orange street lamps were quite insufficient to light the streets so darkness was soon upon us. Aside from occasional cars and trucks passing through and scattered people walking about the town was very quiet. We inquired about hotels in broken Spanish and were directed to what may have been the only lodging in town, Hotel Gerar. Though our host spoke no English, we were able to arrange for a room, storage for our extra bag, and white gas for our camp stove. The hotel also provides transportation up the 4WD track to Piedra Grande but we did not inquire about the cost; our room was 140 pesos per person. There was hot water and the beds were comfortable. It was more than we had hoped for.

We soon ventured back out into the night in search of food, carefully noting our route down the dark narrow streets to the center square. After a few vaca tacos from a street vendor, we sat down in a restaurant and debated what a vaca was. It was not until later in the week that we finally confirmed that our tacos had been of bovine origin. Regardless, they were tasty. After dinner we walked through those market booths that remained open. Nowhere were we approached as tourists, something that I found unexpected and pleasing. It was nice to be accepted in a different culture. Back at the Hotel Gerar, our host was so curious about my altimeter that he brought it up stairs and ladders to the rooftop 6 meters higher to see the numbers change. I followed with some reservations through the inky darkness as we threaded our way up a shaky ladder, past a sewer vent, through a half-finished addition, around gaping holes in the floor of the new construction to the highest point. From the rooftop I could see faint lights glowing throughout the town. Dogs barked, truck engines rumbled, and the breeze blew steadily. It seemed to be a lonesome place. The blankets were heavy and comfortable and we slept very well.

Sunday the 10th of March began with crowing roosters and honking horns and distant music and church bells at the first hint of dawn. The sun rose behind the mountain so when I clambered back up to the rooftop to look around, the mountain was hidden by the bright white glare of the sun through the haze. We packed and then ventured into town to buy supplies and breakfast, leaving the bags at our room. We were disoriented for a moment upon finding the formerly empty square packed full of tents and people and goods for sale. Music surged out of booths, the aroma of hot oil and fried tortillas and fresh fruits filled the air, and the hum and clank of the busy markets surrounded us. We were early and some shops were still setting up. Every imaginable food was for sale - fresh fish, sides of beef and pork, poultry, potatoes, rice, pasta, beans of all sorts, heaps of dry peppers and salted fish and shrimp, eggs, peanuts, grains, spices of many varieties, pineapples, tomatoes, onions, melons, oranges, apples, and yellow and red and green and brown bananas. Blue corn lay husked in great vats of water that would, later in the morning, be used to boil the corn for tasty mid-day snacks. Other vendors sold shoes, plastic buckets, textiles, clothing, music cds, cassette tapes, metal water tubs, tools, kitchen utensils, and miscellaneous household items. Women prepared tortillas from oblong handfuls of dough in wood and metal presses and then fried them on metal grills over charcoal fires. We ate delicious quesadillas and tacos, bought provisions to supplement those we had brought with us, and purchased some beautiful woven wool blankets.

Returning to the hotel to check out of our room, we found some extra space in Jeremy's pack and after filling three 22-ounce bottles of white gas (which turned out to be two bottles too many), we returned to the markets. We bought tortillas and a pineapple, onions, peppers, avocadoes, and a small watermelon that I carried by hand for the first mile of hiking. At last we retreated taking care not to snag tent lines with our ice axes, which protruded from our packs. We set out towards the mountain, having a rough idea of our path from a topographic map in the Hotel Gerar. There was only one road going that way and we followed it in the hot sun toward the hazy mountain that seemed so far away. We were confronted with one problem: there appeared to be a complete absence of public trash cans in Tlachichuca. We were not excited about the possibility of hauling plastic juice bottles into the hills and back, but as we shuffled out of town the trash-strewn gutters only reaffirmed the situation. Not wanting to be seen as arrogant, litter-slinging gringos we warily and reluctantly added our bottles to a curbside as discreetly as possible, feeling very guilty but helpless. On both sides of the road there were dusty fields plowed into dry furrows. The wind picked up spirals of dust that surged across the open expanses in gritty clouds. Hardly 30 minutes out of town we encountered a solitary tree beside the road and made ourselves comfortable in its shade as we devoured the watermelon. It was the most juicy, red, sweet melon I have ever eaten. As we sat in the grass and nibbled on sweet slices of melon, cars and trucks filled with Mexicans returning from the markets bounced by, the passengers waving and calling greetings. I caught the words "living the good life" from one. We certainly were enjoying ourselves.

The mountain loomed above us in the haze and called us on, but the watermelon had affected our judgment and we took to the fields, making a straighter path toward the higher villages visible on the slope above. We slogged through dusty fields as the wind whipped fine volcanic dust in our faces. We had bought 4 liters of bottled water in town to get us to San Miguel, half way to the village of Hidalgo. The town was very quiet. Three men roughly dressed and wearing dusty white wide-brimmed hats played cards outside a store. A young child played with a lariat. We bought more water there as well as a cantaloupe before continuing on. Erin was suffering from dehydration and we all tried to rest and rehydrate. Again we left the road and walked up a dirt path between dry cornfields and fields of young soybean and pea plants. In the hedgerow beside us a steep-sided gully had been cut by runoff in the hard layered ash. It was very deep in places, with near-vertical sides that stood up straight in the soft dusty soil. The erosion hinted at the unpredictable crumbling of the soil that could swallow entire roads, trees, and buildings in a heavy rain. In a grove of pine trees we stopped to eat the cantaloupe, and then wandered on up the slope as the sun sank lower into the haze. The sky had been changing to a deeper blue as we climbed higher but the horizon was still very hazy and we could not see far behind us.

We suddenly found our path intersected by a sharp-sided gully several hundred feet deep. Layers of ash formed colorful bands along the walls and the furrowed fields, plowed by mule, ended abruptly at the edge of the gash in the earth. It looked as if the hillside had cracked open. We marveled at the stability of the volcanic soil and made our way up alongside the gully. The sun faded in glowing orange haze behind us, lighting the beautiful rocky mountain ahead of us in shades of red and gold. Every piece of flat ground was furrowed and dusty and we searched until after dark for a place to camp. Jeremy went on ahead to look for a way across the gully, which was oriented slightly across our desired course, and he discovered the village of Hidalgo not far ahead. The week's announcements were being read over a loudspeaker as we passed by in the night. Only a few orange electric lights broke the darkness. We continued on and crossed the ditch where it ended abruptly at the road. After every rain the road must get narrower as chunks of road collapse into a 20-foot deep hole. The village was dark and only a few people and animals wandered through the streets. All land was cultivated and we settled for a dusty camp above the road just outside of town.

Our three sleeping bags fit comfortably on the tent groundsheet. We did not pitch the tent, for the sky was clear and starry and there were no insects. Through a gap in the pine trees that surrounded us we could see the icy heights of Citlaltepetl tantalizingly close silhouetted against brilliant stars. We must have hiked more than ten miles that day. Dinner was an introduction to Mexican cuisine. We combined dried shrimp (still in their shells), onions, pasta, tomatoes, fresh jalapenos, dry red cayenne peppers, tomato bullion, and several carrots we had found lying on the ground in a dirt track late in the afternoon. The carrots were fresh; the greens were hardly wilted so they must have been dropped by passing horsemen we saw earlier. The shrimp were very salty and rather prickly, and the peppers were very spicy though not intolerable. With some dry sweet bread I had bought in town we ate our fill and turned in for the night.

At dawn the edge of the glacier glowed bright pink. The sun rose behind the shoulder of the mountain and warmed us as we ate oatmeal and devoured the cold juicy pineapple. I was reminded, however, that one must choose foods carefully in the desert or deal with a sticky mess, for there was no water. We packed up and walked back into Hidalgo in search of more drinking water. Animals and small children wandered about the streets. The church was by far the most elaborate building, plastered and painted white and pale green with colorful streamers strung from poles. All of the houses were of rough weathered planks, shoddily fastened together. Horses and mules walked free in the streets. Shocks of straw were stacked neatly on rooftops. Soccer goals of wooden poles sat at opposite ends of the large flat dirt commons, the only flat space on the mountainside. We asked for water at a home and were taken into the fenced yard, where we filled our bottles from a hose tap. We saw only women and children in town.

A shepherd and his flock of sheep passed us on the road out of Hidalgo, the hundreds of feet pattering like raindrops and stirring up a cloud of dust. Above town the road was no longer paved with gravel and climbed steeply through open pine forest with furrowed fields. We left the road at a well-traveled path that seemed to go more directly to our destination. We had some rough maps and sketches of the mountain and knew approximately where the Piedra Grande trailhead lay. The country was beautiful - grassy open pine forest, brilliant blue sky, yellow flowers, and a rugged white snowy mountain not far away across the green and gold hills. To acclimate, we napped mid-day in the warm sun beside a pine tree. We encountered the road higher up in the forest, where the grass had recently been burned. The land seemed dry, but if I scraped the dust aside with my boot I found moist earth just under the surface. The burned tufts of grass had green spikes poking out already. March is the end of the dry season in Mexico and the people may be clearing the undergrowth in preparation for the rains. Perhaps it makes for better grazing lands.

The day dragged on as we climbed in the hot sun through clouds of dust kicked up by an intermittent breeze. The trees thinned out and then vanished entirely and we hiked on over grassy hummocks and hills at 14,000 feet. We cut across where the road descended and finally came over a crest from which we could see the stone hut and concrete aqueduct at Piedra Grande. There were several tents set up below the hut and we pitched Jeremy's tent beside the others, which were for a guided group of five from the States. Our tent seemed small indeed on a sandy flat in a great rocky bowl overlooking hazy hills below. Once the sun sank behind the ridge it became cold quite quickly. Erin was feeling the altitude rather badly. We cooked dinner and I filled water bottles with silt-laden runoff from the aqueduct. The covered concrete channel diverts water across from a gully to the hut and then back to the gully below the hut. It also serves as a sidewalk extending a short distance up the slope and making the first bit of hiking very easy. We left the bottles to settle overnight and settled ourselves into warm sleeping bags. I was very alarmed to see my water turn bright cobalt blue when I poured a small quantity into my bowl to rinse it after dinner. We were using iodine tablets rather than my purifier for water to save weight, and I was not expecting to see the reaction between iodine and starch. It was rather amusing.

The temperature was below freezing in the morning and our water had begun to freeze. Clouds obscured the higher slopes and high cirrus clouds overhead indicated a change in the weather. After breakfast clouds obscured the sun. The folks staying in the hut and the team camped next to us planned to hike up high to acclimate and return for the night before attempting the summit the next day. We packed up everything, intending to sleep up high. It was slow hiking on the steep loose scree. We were soon in the clouds. Finding a suitable established campsite just a thousand feet higher, we stopped mid-day and set up the tent in one of several circular stone walls built by previous campers. It was an excellent site, perched on a flat area at 15,200' and far enough from the cliffs nearby to be safe from falling rock. We heard boulders tumbling into the gullies from time to time. No water was running since clouds hid the sun so I collected snow and ice and Jeremy set about melting it on the stove. We were carrying an excess of fuel so we boiled some of the water to purify it. We ate early and sought warmth in our sleeping bags early in the evening. I had to go out once after dark to bring the packs into the vestibule when wind-whipped snow squalls battered the tent.

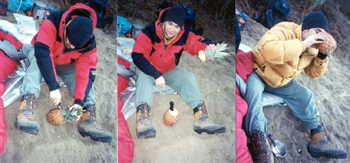

Jeremy and I departed at 4am under starry skies. Erin, still feeling the altitude, opted to stay down. It was well below freezing as we set out by the light of our headlamps. Several lamps flickered in the ice gully high above us. We walked cautiously with our ice axes for support, moving ever so slowly up the scree. We kicked steps up steep frozen snow in the gullies, unable to see the bottom below or the top above us in the darkness. Two hours later we reached the glacial moraine and stumbled out onto the loose rock to wait for daylight. It was cold, bone-chillingly cold, in spite of our warm clothing. In the thin air at 16,000 feet we felt weak and huddled in a gully while the eastern horizon became pale yellow, then bright orange, then brilliant red. When it became light enough to see, after 20 minutes or so, we climbed up to the glacier and put on our crampons. The ice and rock mingle together without any change in terrain so it was not difficult to get to the crunchy snow surface.

Two climbers well ahead of us were moving fast up the mountain. We later learned that they had been climbing on the mountain for a week and were thus well acclimated. A roped team of three waited off to the west and started climbing once we were past them. Jeremy and I climbed solo, the crumpled ice being mostly free from crevasses because the slope is concave. At first we chose an arbitrary path, but when we paused once I planted the spike of my axe firmly in the ice and heard a "whump" from the glacier as if it had just cracked or settled. We moved on with haste and followed the Normal Route marked by wands. The snow had been melted and re-frozen into a latticework of ice that crunched underfoot and made for solid holds. We paused often and held a steady pace. As the sun rose, it lit the glacier in orange and gold light that quickly turned to a brilliant white. My ordinary sunglasses were insufficient to dampen the glare. To the west we could see the summits of Izta and Popo protruding above hazy white clouds. Below, we saw our route of the past few days laid out like a map. From our snowy perch the little towns looked tiny and very far away. Higher on the glacier the slope steepened past 45 degrees. We spotted our tent far below. The well-traveled path zigzagged up the snow toward pinnacles of orange rock that seemed so hard to get to.

At 9am we were at the crater rim beside the Ice Needle, one of many fingers of shattered orange-brown rock that lean out over the crater. The ice on the eastern slope of the mountain was frozen into hard pointed teeth that were angled up into the slope and were difficult to walk through without chopping a path. It took much so effort to move at 18,000 feet. The crater was very impressive - vertical walls dropping hundreds of feet to a flat floor, pinnacles of rock leaning over the caldera, sulfurous gases wafting out in the light breeze. The crater was not far across, perhaps deeper than it was wide. Mold-like gray fuzzy mineral formations grew on some rocks. I rested briefly at the rim, photographed the crater, and then retreated to a more friendly altitude a thousand feet down. Jeremy traversed around to the true summit part way around the crater, where the ground was bare and a tangle of iron crosses adorned the highest point. He joined me 45 minutes later where I was napping on the steep ice slope. The view was spectacular. Clouds began to form around the high summits later in the morning but otherwise the sky remained clear. The hills below were rugged and beautiful. In the hot sun the snow became soft, but we descended with care down to the end of the ice. Descending the ice gullies was much easier by daylight since we could choose the easiest route and kick steps in the soft snow.

We met Erin at the tent; she had climbed to the glacier, explored the lower slopes, and bouldered on the moraine. Though it seemed much later, it was only noon. We devoured two freeze-dried meals left by our friendly tent-site neighbors and then rested in the sun, deciding to sleep another night up high rather than hike down. The view from our tent site was amazing. The hills below curved over the horizon as if we were looking through a giant fish-eye lens. We filled bottles with silty glacial melt water, ate another meal of pasta, and went to sleep. Jeremy and Erin were both having trouble sleeping at altitude so we decided to get down early in the morning. I've found my altitude ceiling to be around 17,000 feet, below which I feel fine and above which the altitude headache catches me. I've never had trouble sleeping high though. But even after three nights above 14,000' I still was not acclimated enough to walk quickly up the aqueduct to fetch water.

Descending the scree slope in the morning was more difficult than climbing it had been. We stumbled into Piedra Grande and heated water for oatmeal. After filling our bottles from a puddle in the still-dry aqueduct (which would fill once the sun began to melt the ice above) we hurried down the road to Hidalgo. We stayed on the track, but it would have been shorter to take a shortcut through the pine forest like we had on the climb up. Once again the weather was sunny and warm and the road dusty. As we arrived in Hidalgo a man parked his green pickup beside the road and got out. We inquired where we might find a ride to Tlachichuca and he happily led us to the corner where, he said, his friends would be passing by shortly. Minutes later a couple of trucks approached. He flagged down the first and we hopped onto the back of a wooden-railed pickup truck. Traveling with us there were two women with baskets of flowers going to the cemetery in Tlachichuca, a woman with two small children, two Mexican men, and two climbers who had hiked down ahead of us. Moments later we were careening down the gravel road over the ten miles we had taken the first day to climb. It was well that we had walked in, since we needed to acclimate, but the quick ride down was much appreciated by all of us. I gave the driver a few dollars when we arrived in Tlachichuca.

In town we bought a watermelon and some tacos, recovered our bag and signed the logbook at the hotel, and bought bus tickets to Puebla. After two hours of dusty hazy bright sunny Mexico we were once again at the bus station in Puebla. We approached one of the taxi drivers soliciting business in the terminal and he led us to his taxi, packed in the bags, and took us to the Hotel Villa Real in the city historic center. We had located the hotel in an information booth at the bus terminal. Our room was very nice, with hot water, for 480 pesos a night. We showered and ventured out to the town, which was quite lively for a Thursday night. Dinner was very good and very inexpensive compared to the American equivalent. After dinner we walked through the park, which was enchanting with the palm trees brightly lit and the grass bright green and the balloon sellers walking through with huge bundles of colorful balloons and vendors selling food and drink. We were completely lost but navigated back to the hotel by the orderly arrangement of streets numerically to the norte, sur, oriente, and poiente.

We slept late the next morning but even so we had to wait for the shops and restaurants to open later in the morning. We enjoyed and excellent breakfast and then located the market section, where dozens of booths sold pottery and textiles and silver and handcrafts. Most customers were Mexicans and I did not feel as out-of-place as I had in Africa. We spent the morning there, and then set out to explore the rest of the city in the afternoon. Calle Cinco De Mayo was bustling with foot traffic and shoe shiners and balloon sellers and the occasional beggar. We especially enjoyed the orange juice sellers. They plied the streets with shopping carts full of oranges, which they squeezed to produce giant cups of sweet juice that sold for 5 or 10 pesos. We passed meat markets, bakeries, basket weavers, sellers of dry corn and rice and beans and peppers and spices, fruit sellers, fish sellers, stores selling plastics of every type and form, carpentry shops, mechanics, paint stores, shoe stores, sellers of hardware, book stores, music stores, and sellers of every other imaginable product. Sidewalk vendors sold boiled corn, fresh fruit, ice cream, and fried snacks. Mid-afternoon we made our way back to the hotel, went out for dinner, bought ice cream, sat in the park for a while and gazed up at the shiny black sky behind brightly lit palm fronds and tree branches, admired the church towers, listened to the music drifting in from stores and musicians, and talked until late at night.

We found the bakery in the morning, after breakfast. The bread and cakes were very inexpensive but some were dry and had been out in the air for a day or two. We purchased 40 pesos of delicious pastries, two bags full, and checked out of our hotel. The staff called a taxi grande for our many bags and we were quickly shuttled to the bus station. As we approached the station we observed a great cloud of black smoke and I feared that the bus station itself was burning, but it was a large commercial store directly across the street from the main terminal that was engulfed by fire. Not many people seemed to be concerned and we continued on our way, purchasing tickets to TAPO in Mexico City for 65 pesos each on Estrella Roja. The AU buses cost the same but the Estrella Roja buses were nicer and less crowded and easier to find in the terminal. At TAPO a driver led us to his taxi, which was a green and white Volkswagen Beetle. Fleets of Beetles make up part of the Mexican taxi system. We told him we needed a larger taxi but he insisted we would fit, and indeed we did! There was no passenger seat and he managed to pack us all in. We asked for a good cheap hotel and he took us to the Hotel Plaza Madrid, which was by no means cheap but was quite nice. Breakfast was included so that lessened the burden of the 650-peso charge for a room.

We were not impressed by Mexico City. Our hotel was in the city center but there were few people about on a Sunday afternoon. The side streets were trashy, and even though the air was relatively fresh at that time of year, it was still very hot and uncomfortable. There was a '60s's rock concert under the Monument to the Republic but the audience was small in number. Restaurants were closing down early in the evening and we walked around for a while looking for a place suitable for three ragged travelers. We ended up at a seafood place with live entertainment and delicious food. It was a change from the usual fare and though the music moved on down the street soon after we arrived, we enjoyed the meal. As we walked back to the hotel after dinner the setting sun lit the cloud edges bright orange. A warm breeze rustled in the palm fronds overhead. We ate ice cream and walked slowly along cobblestone sidewalks, circling until we found our hotel. Early in the morning we took a taxi to the airport and caught a flight back home.

For one week I escaped to Mexico. I explored the bus system, saw what life was like in the most remote villages, walked through the street markets and sampled the cuisine of the region, hiked through warm sun-splashed meadows and climbed on the snowy heights of Citlaltepetl, peered into the crater of the volcano to see what lay within and then, satisfied, hurried down to the city where I walked the streets and listened to the music and watched the people and explored the markets. I saw a tiny bit of Mexico and then returned to New York and settled down to work once again. One can learn so much in a single week; traveling opens the eyes to the world and gives life a little more meaning.