Africa seemed like a distant, wild, exciting place.

I was in college, with a heap of money from six months working for NASA, so when winter break came I got on a plane to Nairobi and set out to see the Serengeti and climb the highest mountain in Africa.

to the index page

African trips tend to start in Europe for Americans following the tourist corridors, and my plane to Nairobi would fly from Heathrow. Sitting in the terminal at Newark, I watched the sun set in beautiful hues of purple and orange. It was a farewell to America - first light would find me far, far away and in spite of the calm and beautiful evening but I couldn't help but feel anxious. I hadn't done much traveling in distant places, especially not on my own. I didn't sleep at all during the short night over the North Atlantic. The glowing video screen in front of my seat read off an outside temperature of -90F and a tailwind of 140mph, not pleasant weather to be out fishing on the ocean below. When we arrived in London it was still completely dark, even at 8:00am local time, and the lights of the city below shone brightly. The patterns of streets and lights appeared distinctly different from those in America, more scattered with curving streets and abstract patterns that one might expect from a city laid out hundreds of years ago.

Since I had an entire day layover in London and had not seen any of Europe, I went into town to learn what life was like in that foggy gray city. Paddington Station was quite impressive with its cavernous, arched interior and purple-robed attendants and the train I rode was the quietest and smoothest I have ever been a passenger on. We sped past residential neighborhoods, industrial sections of town, sometimes slowly and sometimes so rapidly that the air slapped the cars hard as they passed bridges and entered tunnels. The city was fascinating. I only saw a tiny bit of it, but that was enough to see the speeding black BMW taxis, double-deck red buses, quaint red phone booths, brown and red brick buildings of classic English architecture, picturesque gardens and hotels, and restaurants serving every cuisine of the world. Pigeons, black and white and every intermediate color, hopped and flew around the wet sidewalks. People from all over the world walked the streets (I heard many languages) and everywhere I heard that crisp British accent. Uniformed English policemen were about and occasionally a red fire truck or a police car with screaming sirens sped past on the narrow streets. I wrote some letters at an internet cafe, sent a post card at a post office, explored the shops, bought food, took many photographs, and wandered in erratic circles as each new attraction lured me on. After an hour or so I was quite disoriented but I wandered a while longer before locating the station and taking the train back to Heathrow.

From one end of British Airways Terminal Four, I looked across an enormous hall. It was long enough for 88 wide check-in desks to be lined up along one side. There were thousands of people about and I could not check in for my flight until three hours before departure. One can go almost anywhere from Heathrow - there were fights leaving that afternoon for Sydney, Dubai, Kuwait, Tehran, Buenos Aires, Amsterdam, Paris, and more. At 2:00 in the afternoon the sun was already low, a sign of how far north London is. The night is 16 hours long; it must be even longer in Ireland and Scotland.

28 December 2001

I was quite surprised to wake to bright sunshine 6 hours into the flight to Nairobi, having slept a little more than three hours. I do not often sleep on aircraf. Still on the move, a day later, I was far from home and going farther. We flew over clouds for some time but when they cleared I watched hundreds of miles of gray and green rocky plains pass by. At last, the Green Hills of Africa lay below. I was surprised by how expansive and empty and huge a continent Africa is. Our descent brought us lower over sparsely populated, thinly forested grassland with occasional dirt tracks and scattered buildings. The airport was a partially forested field with runways and several terminal and hangar buildings. The concrete control tower rose from a clump of distinctly African flat-topped acacia trees. I looked around anxiously for a runway but saw nothing but tree-studded grasslands. Fortunately there was a narrow strip of concrete that seemed hardly large enough for a bush plane, though our 747 landed on it. We taxied to a terminal, which emerged from a cluster of trees as we approached, and disembarked into the airport. I kept watch for the giraffes I was certain must be wandering among the hangars.

Immigration consisted of filling out an entrance card and a three-minute wait in line for a hastily issued passport stamp. It is good to sit near the front of the plane to avoid waiting with 400 other people at immigration. There were ten of us there in Nairobi and we would meet an eleventh in Arusha. Mike's and Hanna's luggage had been lost by Northwest Airlines somewhere between Denver and Gatwick, so they were quite concerned. The rest of us fared better with our bags but we were all tired. Customs were very informal, a wave through with no questions. Kimbla Safari representatives met us at the airport, holding small signs in a pressing throng of many other people holding signs. Quickly we were on our way to someplace else. We piled into two Toyota minibuses and were presently lurching through the streets of Nairobi, not sure where we were going but content to trust our drivers. People ran to and fro in the midst of the speeding traffic, missing collisions by the narrowest of margins. The traffic itself was interacting in a similarly unsettling fashion.

The first thing I noticed about Nairobi, aside from the perpetual sense of impending disaster on the streets, was the smell. The aromas of automobile exhaust, hot dirty pavement, roadside ditches, wood fires, burning rubbish heaps, freshly dug soil, wet plants, dusty air, and thousands of people all mingled together to form a distinctive atmosphere. One must visit in person to learn the smells of a place. Sights and sounds can be experienced in photographs and recordings, but to truly understand how a place is one must be immersed in it. After dropping our bags in a hotel, we broke up into haphazard groups and explored the places within walking distance, dodging cars and hawkers of goods to explore the Westlands markets and the Nairobi museum. We were told that while on safari we would have a chance to shop markets that were better and had lower prices so we just looked around. The advice was well taken. One can get surprising deals for a ballpoint pen or a pair of sunglasses outside the city. The museum was quite interesting but induced drowsiness. That may have also been a result of no food, little water, and a long day after two days with time changes and very little sleep. Walking back, we passed street side mechanics that had set up shop with cars propped on rocks and logs while wheels were battered back into shape. Carpenters crafted exquisite furniture from rough planks and scrap crates in another dusty turnout. Tiny booths of poles and sackcloth lined the alleys. It was hot.

The Mayfair Hotel, now a Holiday Inn, is beautiful. There are lush gardens, a pool, restaurants, and shops. The guards and staff are numerous and even the brick walkways are polished. We were happy to have the quiet courtyards because the outside was a wild place. Taxis honked incessantly at us trying to solicit business. A taxi crew seemed to consist of a minibus with many people leaning out of various doors and windows all yelling for us to ride. The people are so poor that western culture is available only to the wealthiest. High walls topped with multi-strand electric fences and barbed wire surrounded nightclubs. Many stores were still closed for the holidays, locked and barred and boarded up, the owners having gone out of the city to be with their families.

29 December 2001

Andy, Erin, Opus, Hanna, Mike, and I went to an excellent Indian restaurant in the shopping complex at Westlands. It was a ten-minute walk from our hotel, and the food was extremely good and inexpensive. $25 USD got me through a day's water, museum admissions, and dinner. As we walked back to the hotel after dark we were followed by many more alms-seekers than there had been by day. Most of them were very young and walked beside us with outstretched palms, mumbling something quietly. They sometimes followed us for a minute or two but never blocked our way. With our group of six on the main street it seemed relatively safe, but it was very dark. It's best to avoid walking about after dark in Nairobi.

Breakfast at the hotel was delicious. Afterward we piled into two minibuses for the drive south - Andy, Drew, Mitch, and I in one vehicle and six in the other minibus. For an hour or so we bounced along two-lane roads outside Nairobi, passing through open plains with those flat-topped African trees scattered thinly. Then the road became quite narrow and we drove into hilly Maasai country where people wearing brightly colored cloths herded animals and milled about at the roadsides. Often they called and waved for money. Their simple mud huts were scattered in the trees.

The border crossing was hectic, to say the least. People hawked goods and thrust the in our open windows. We had to get exit stamps on our passports, transfer to a larger Tanzania-registered bus, and obtain entrance stamps. All the while Maasai vendors surrounded us. The women had one tactic that was particularly effective: They would attach a beaded bracelet to one of us. There was no escaping - it was there, and it was a gift from "mama maasai" and could not be returned. Then the giver would implore to have her photo taken, which would cost a dollar. I paid the dollar but didn't take the photo, having no desire to take a photo of a lady in a parking lot dressed up unnaturally with excessive beads shipped directly from Asia and holding goods to sell made in some distant village for next to nothing.

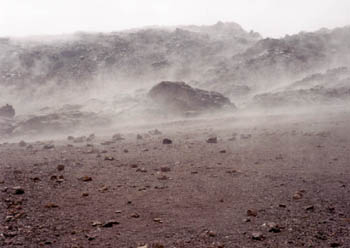

In Tanzania we climbed high on the shoulder of Mt. Meru, where the treeless dusty hills could have been in Mongolia from the looks of them. Wind swept the dust in great clouds. Herds of cattle scattered about the brown grassy hills were diminutive. The fine dust was stirred up by the slightest disturbance. This year the rains did not come in October so it is dry. We descended and drove through more villages and markets. A trading post with many hundreds of people was particularly colorful and impressive. In the lower, moister country we encountered groves of banana trees and lush rain forest.

In Arusha we were brought to the home of Mr. Jordan, the owner of Tanzania Safari Adventures. Staff with hot towels and cold glasses of mango juice met us. We went into town to change money and when we returned Livia had arrived from the Ilburo Lodge, where she spent the night after flying into Arusha the night before. We ate an excellent meal and met Mr. Jordan and then Peter Mato, our guide. Peter had climbed the mountain 500 times and was renowned as one of the finest mountain guides in Tanzania.

On our bus with Peter and a few staff, and all our food and equipment added to the already cramped quarters, we continued on our way around the base of Meru and then Kilimanjaro through increasingly volcanic country. Boulders were scattered about where they had fallen from the sky and small cinder cones poked out of the dusty hills. The quality of life in Arusha, and in all of Tanzania, appeared to be much better than it is in Nairobi. People live more traditional lifestyles in the countryside and appeared to be better off. Still all the people are struggling. To our left the lower slopes of the mountain rose into summit-hugging clouds. From the size of the hazy mountain we did get an idea of how huge it is though. The land to the east of Kilimanjaro had a ravaged, burned-out look. Since the rains had not come the crops that normally covered the fields had not been planted, and the land looked barren. Twisted trees and scattered mud houses stuck out of the landscape awkwardly.

We turned left and drove ten kilometers up a small road that climbed steadily higher to the Capricorn Hotel at 5000 feet. High in the hills, the lodge had beautiful gardens but sparse rooms. I heard that some rooms were much nicer than ours. The electricity went on and of unpredictably; a candle and matches were provided with good reason. It was nice to relax after such a busy day; I had seen so much, and it all seemed to blur together.

30 December 2001I watched the sun rise from outside the hotel. While it was still dark, roosters crowed and innumerable wild animals made strange sounds that echoed among the hills. Low clouds and haze clung to the horizon so the sunrise was washed out a bit. Temperatures were quite mild but we expected to be hiking in sub-freezing temperatures soon. As I wandered about I met a guard reporting for work at the gatehouse. He was armed with a bow and 5 or 6 iron-tipped arrows and expressed to me through signs and broken English that they were for shooting intruders in the leg. I had at first though he might be hunting some sort of animal. What a great deterrant though! Thieves could count on a guard being hesitant to fire a gun, but an arrow in the leg surely could happen, silently and without warning.

Breakfast was similar to the meal the night before; there were few choices but the food was good. We departed at 9am and rode in a Land cruiser and a Toyota minibus up the narrow, steep road to Marangu Gate. Along the way we passed a spectacular overlook of the snow-covered summit and the crags of Mawenzi beside it. The summit was just beginning to be obscured by clouds, which form every day between 9am and 11am as moist air from the coast moves up the slopes and condenses. The clouds obscured the summit moments after we finished snapping photos. We had a very long traverse to make - the mountain looked to be quite far away.

At the gate we milled about for an hour or so, signed in, met the porters and guides (Peter and 24 others, no less), and browsed the gift shop. Mike and Hanna rented the gear they needed; their bags were still lost in transit. The introduction by Peter Mato was quite lengthy and, at times, a bit confusing because of the language barrier. He speaks well but the words do not always flow. All of us are trying to learn some Swahili but I find it difficult to remember words without seeing them written. The porters, let by Peter, sang welcome songs and presented each of us with a gold-tasseled lei to celebrate our climb. We eleven stood in the middle of the path, dressed in our boots and hiking clothing, our packs at our feet filled with the latest in waterproof shell clothing, camera equipment, and outdoor electronics. Lined up above us on the hill, the porters looked desperately unprepared. On their feet they wore worn-out sneakers or work boots with twine for laces; one or two had an old pair of hiking boots. Cotton t-shirts and tattered shorts were all they had for clothing. We gazed up at them, I feeling quite out of place and privileged to be climbing the mountain that towered over the country these people called home.

All the porters but one, Richard, went on ahead by an access trail while we took the scenic route. Peter led and Richard brought up the tail end. Higher on the slopes we would be allowed to hike in broken groups, but in the jungle it was not safe to do so because locals were known to accost travelers. It was also nice to be together because Peter was pointing out many interesting plants and animals and recounting historical facts. We climbed past jungle overlooks and cascading waterfalls, saw monkeys swinging in the trees, admired beautiful wildflowers, and chatted with each other as we walked slowly up the very well maintained trail.

Lunch was a surprising affair. At the stopping place the porters had laid table cloths on the rough plank tables, prepared plates of sandwiches, vegetables, fruit, boiled eggs, and chocolate bars, heated water for us to wash with, given us bottles of fruit juice, and presented each of us with a foam camp chair to relax in after lunch. After a leisurely meal we continued at our slow pace through higher, less-lush jungle. Eventually the vegetation became nearly homogenous, of one type of tree that became shorter and more moss-covered as we climbed higher to the Mandara Huts at 9000 feet.

The huts numbered six or seven tourist huts, and the same number of porters' accommodations lower on the slope. The porter huts were also used for cooking and were packed full of people, but our huts were recently refinished and very nice. A large dining hut served as the common area and was spacious enough for several parties to dine at once. Two years ago the Marangu Route was improved - the trail reconstructed and the huts refinished. Each A-frame hut had two rooms, and each room had four mattresses. The doors were fitted with heavy padlocks, enabling us to secure our equipment. For the duration of the trip I was allowed to claim the high bunk in my hut, as I was the only one enthusiastic about sleeping there. The eleven of us split 4-4-3, and I was lucky to be in the group of three. The hut was quite cramped even so and we were happy to have the extra bunk for storing gear out of the way. We gathered in the dining hut for tea and snacks before settling into our rooms. The beds were quite nice - each thick foam mattress was covered with blue fabric and the interior paneling was smooth and varnished. The tourist and dining huts were outfitted with solar panels and batteries to power small fluorescent lights. However, only those in the dining hut had charged sufficiently. The condition of the huts was much better than I expected.

Before dinner we walked to Maundi Crater. In the forest we saw blue monkeys swinging in the trees, and we emerged from the jungle into the open moorland just as the sun was setting and the views were astounding. The crater is a grassy bowl about 200 meters wide. From the rim we could see far into Kenya; Peter pointed out distant hills and lakes. The summits of Kilimanjaro and Mawenzi were still obscured by clouds but they began to clear as we departed at dusk. Dinner was an excellent meal of Lake Victoria fish, fried potatoes, carrots and summer squash, fruit, and vegetable soup. The staff certainly took good care of us. After dinner, at about 8:30, we all turned in for the night. We had divided ourselves into three huts: Jon, Mark, Drew, and Mitch in one hut, Opus, Erin, Livia, and Hanna in another, and Mike and Andy with me in a third. That camp in the high jungle at 9000 feet was the most exotic I've ever had. There were monkeys in the trees all around us. The birds never shut their little beaks to let us sleep! The whirring insects were hideous. And, when I had to go out to pee in the middle of the night I was sure that the squirrels must be the size of large cats by the great crashing they were making in the trees above my head. Strange hoots and squawks and echoing roars and screeches bounced among the dark trees and it sounded like I'd be ambushed at any moment by something furry with sharp claws. Fortunately, in the interests of my rest, I was not taking the Diamox mountain-sickness medication like the others were because it is a diuretic and everybody else was dodging grasshoppers at the edge of camp several times a night. Having adjusted well to the time change, I slept soundly.

31 December 2001

I awoke at 6:15 and washed as the sun rose above very pretty clouds to the east. At 9000 feet we were above the cloud tops, which glowed in hues of pink in the morning sun. Tea was served to us at our huts, and 45 minutes later we all gathered for a breakfast of juice, fruit, porridge, eggs, sausage, sauteed vegetables, toast, and tea. Under sunny skies with temperatures in the 60s, we set out at 9am to look for monkeys along the trail. Hiking slowly and quietly, we arrived at an overlook just as the clouds were starting to obscure Kibo and Mawenzi. Peter had delayed our departure with the hope that it would increase our chances of spotting the elusive Colobus monkey. The other climbing parties left well before us so the trails were quiet when we passed by, and sure enough - he saw monkeys! Peter knew exactly what to look for and spotted the animals in the trees as we walked obliviously past. The big black and white Colobus monkeys stared shyly at us while smaller blue monkeys swung about the trees at the edge of a meadow.

We rested on the ridge for a while and then continued through gently sloping moorland, broken into smaller groups with Richard ahead and Peter behind. In the open it was safe to hike alone (in the jungle the locals are known to accost hikers) and we each proceeded at our own pace or in small groups. The ascent to 11200 feet, our appointed lunch stop, took us into the clouds. It was a great relief to see the mist come in because it brought moisture and shade. Temperatures were in the upper 60s. Occasionally we could see the craggy spires of Mawenzi through breaks in the mist. Along the trail we saw many lizards and some very pretty flowering plants. There were many people on the trail, unlike the day before, and we met many descending climbers and porters. Peter had warned us not to ask about the climb - lest we become discouraged - but the faces of the returning climbers said enough about the difficult climb that lay ahead.

The Horombo Huts are clustered on a misty overlook beside a small stream. When we arrived the mist was quite thick and it had become rather chilly. Even so, I immersed myself in a small pool of water and washed one of my shirts - though I am not sure whether I made it cleaner or dirtier by washing. Horombo is actually a small village, a stopping point on both the climb and descent and the place where we and most of the other parties would spend a rest day. The huts sleep 120 climbers, and there were tents as well. The guides and porters disappeared into their huts so we saw little of them even though there must have been several hundred in camp. We assembled in the big dining hut for tea and cookies and lingered there for some time, talking and watching the mist drift past the windows.

I retired to my hut, which I settled into quite comfortably for the two nights we would stay. Small animals the size of mice but striped like chipmunks scurried about outside, and the ravens squawked awkwardly as they hopped about hoping to find food. The paneling inside our hut had written on it names from all over the world: Singapore, Mexico, Poland, Japan, Scotland, Belgium, Canada, Uruguay, Italy, and the States. In camp I met climbers from Germany, England, Canada, Argentina, and various locations in the US. We all gathered to celebrate New Year's Eve.

Clouds on the horizon washed out most of the sunset colors, but the mountain cleared and the glaciers glowed golden in the last rays of the setting sun. Dinner was excellent - as always, the service was outstanding and the food delicious. We ate fried chicken, rice and vegetables, hot soup, and fresh fruit, and we finished the meal with tea or cocoa or coffee. When we stepped outside, away from the faint glow of the fluorescent lights in the hut, we were amazed to see a brilliant starry sky overhead. The moon had not yet risen and the sky was clear. Far below, the lights of Moshi twinkled in the night.

1 January 2002

At midnight Peter and some of the porters began to parade around camp dancing and singing in Swahili. I was asleep, but some of our group had joined in. They circled around and soon there was knocking at our door. With much festivity, no doubt partially induced by a few beers among them, the guides presented each of us with a New Year's card and wished us well. I awoke to a fine morning at 6:30. The rising sun shone on clouds below us and illuminated the mountain and the huts with golden rays. Tea was brought to our door once again, and we sat in the sunshine and sipped tea and packed for a day hike up the trail. We gathered outside the dining hut at 8:00 for a celebratory breakfast. We looked out on a sea of clouds, broken by hazy distant peaks, and above us the spires of Mawenzi and the snowy summit of Kilimanjaro shone bright against the deep blue sky. The tables were set with a very colorful and delicious breakfast of fresh fruit, porridge, French toast, bacon, sausage, and all the trimmings. One of the porters had a small radio and it cheerfully played a fuzzy New Year's service and '80s tunes from somewhere in the world. Everyone was in high spirits.

After second helpings of food were finished a procession of porters came down from the huts, singing and clapping and bearing a freshly baked New Year's cake. Frosted white and elegantly decorated, it was a remarkable culinary achievement at 12,000 feet. The candles refused to stay lit in the thin air and light breeze. The attempts were abandoned when Peter led another festive procession down the slope, dancing with a bottle of South African champagne. Peter immediately launched into an elaborate ceremony. The crackling radio was turned off and three couples were selected and brought to the head of the table. Under sometimes-hilarious instruction by our noble guide, they ceremoniously cut the cake and fed each other to much singing and clapping. When this was completed Peter seized the champagne and began to prance around the table, shaking the bottle and pointing it at each of us to emphasize his oratory as we scrambled for cover. Finally, with superhuman effort, Peter managed to pop the cork. The champagne rocketed upward out of the bottle and showered those who stood too close. The damage was less than we had expected and we crowded around to receive our minuscule doses of the remaining champagne to toast to the climb. We also received bottles of Coca-Cola, in the old, heavy glass style. The cake was divided among us all as we dispersed to get ready for the day's hike.

The fog moved in as we began to climb. It was nice to be carrying a light pack, with only a rain shell, water, cameras, and first aid. I had been carrying most of my things even thought he porters offered to take them all. It was very pretty hiking below the crags of Mawenzi, which loomed quite close. We climbed above the mist to the Zebra Rocks - an overhanging rock face that was streaked black and white by mineral-laden water. We continued on to an overlook across the Saddle - that huge flat expanse of alpine desert that lies between Mawenzi and Kibo. From a viewpoint at 14,400' we caught a glimpse of the Kibo huts across the saddle at the base of the final escarpment to the crater rim. By that time clouds had obscured the summit. It was cool, with a light breeze, but Peter said the weather was unusually mild. I was comfortable wearing a long sleeved sun shirt and nylon pants.

We descended to Horombo and found very thick fog, which lay like a blanket over the huts and silenced the usually busy camp. Mist wafted in the open door and cut visibility to ten meters at times. After a lunch of chapattis, beef with vegetables, thick fried potato chips, and very delicious watermelon, vegetable soup, and the usual tea, most of the people retreated to their huts or sat in the dining hut reading or writing in journals. By 3pm the fog had become so thick that droplets began to condense on every surface. The mist rose steadily up the slope but there appeared to be no air movement at all. The clouds alternately lifted and fell, giving us glimpses of the sunny valleys below.

Just after sunset the fog finally cleared off the mountain, great puffs of mist sliding down the slope like deflating balloons as darkness fell. We stood outside looking out over Moshi and the hills beyond, talking about the climb. Dinner was delicious, the menu of the night being pasta with vegetables, green beans, soup, and fruit. When we emerged the darkness was complete and the full moon had not yet risen, so the stars were absolutely spectacular. I could pick out a few familiar stars but most of the sky looked different.

2-3 January 2002

The cool mountain air sent us into our sleeping bags quite hurriedly. I rose before dawn to watch the sun rise from a prominent point a short distance down the trail. The sky was clear and starry at first, and then began to glow in shades of pink and blue. Feathers of pink cloud shimmered over the glaciers on the summit. As the brilliant orange sun broke over the horizon Mawenzi and Kibo glowed brightly. After breakfast we proceeded on up the trail to a ridge top that overlooked Mawenzi and the entire Kilimanjaro massif. A few wispy clouds were approaching and as we continued on after photographing the mountain many times over, the clouds moved in. Walls of mist crept up behind us. We descended into the saddle and looked across a huge expanse of desert that sloped upward toward the Kibo huts. Boulders of all sizes lay scattered about where they had fallen from the sky long ago. We proceeded slowly, not because of the thin air but rather as a preventive measure. I found my pulse to be elevated, but my breathing was normal. We broke for lunch at 14,500 feet, within sight of the Kibo huts a thousand feet higher. The meal was the usual fare: peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, soup, vegetable sticks, boiled eggs, snacks, and fruit. Ice pellets began to fall and we packed up and continued on. Curiously, clouds had been converging from both sides at the ridge top. Snowflakes followed, heavy and wet, and accumulated thinly on rocks and pebbles.

The Kibo Huts are fewer in number and of different construction than the lower huts. One large rectangular stone building with 5 or 6 bunkrooms housed most climbers; some parties pitched tents outside. The porters and camp attendants resided in wood-framed buildings nearby. We packed, prepared for our midnight departure, drank tea, and tried to adapt to the altitude. I had acquired a slight headache but was otherwise feeling fine. Dinner was light and hurried, as we would try to sleep from 6pm until 11pm. I would have succeeded but most of the others did not; those taking Diamox to help prevent mountain sickness suffered from the diuretic side effects and were frequently getting up. I sleep as well at altitude as I do down low, perhaps better on account of the strenuous hiking. I managed to sleep three hours even so. Livia was not feeling well and decided to return to Horombo midway through the night, so after helping her pack and sending her down with three porters we dressed and stretched and hydrated to prepare for the climb. The cases of mountain sickness outside were numerous. The human body is not meant to live at 15,500 feet, and some felt the altitude more than others - we saw several vomiting victims and many more sitting dejectedly on the cold gravel.

After tea and cookies we departed at midnight, joining a line of headlamp-sporting climbers. The lamps were not necessary because the moon and stars shone brightly, and the lights often became annoying. Peter and the two assistant guides, Nickas and Dismas, rotated through positions at the lead, tail, and mid-line. They chanted and sang quietly and held a very slow pace that was to become our rhythm of life for the next seven hours. We overtook several parties even so. The mist had been moving in and out and for a while I was concerned that the clouds might obscure the summit, but they eventually cleared away. The trail first wound its way up a gentle slope that got ever steeper as it approached the base of the scree. Once on the scree, inclined at 40 degrees, we followed a well-packed path that wound its way through the loose pebbles. Behind us, the spires of Mawenzi shimmered in the moonlight. Scattered lights in the valleys below twinkled brightly. Low clouds and fog hugged the lowlands. Above, the slope rose steeply and then fell back, so we could not see the crater rim. We paused at Hans Meyer Cave, little more than an overhanging rock that marked the halfway point. The upper reaches of the climb to Gillman's Point were strewn with boulders, and without our guides it would have been difficult to follow the trail. I, of course, was delighted to be scrambling at 18,000 feet, but was reprimanded occasionally for straying off the trail in my enthusiasm. Most of our party plodded laboriously upward, having no spare breath to converse and little interest beyond taking one step at a time.

As we approached Gillman's Point the Ibuprofen I had taken to prevent headache began to wear off, and soon after mountain sickness hit me quite suddenly. I pushed on and presently found myself at Gillman's. The group had become divided into three sets, each with one of the guides. We rested briefly and then continued on. I had made the entire climb following directly behind the lead guide, but after Gillman's I fell back and concentrated on moving forward and photographing the sunrise. The climb after that point blurred together in my memory, two hours that seemed like twenty minutes. We skirted the precipitous rim as the eastern sky brightened and the pink glow began to shine on the glaciers, hills, and valleys that spread out before us on the summit. The ash pit, the true crater, was nearly hidden on a far hill, and instead we looked down into a boulder-strewn valley with patches of snow scattered about.

At times we crept past vertical drops of more than 30 meters to the valley floor. Ice walls ringed part of the crater and we hiked past the glacier we had been admiring from the lower camps. The ice was clearly retreating. In the 1880s, when the first climbers succeeded in reaching Uhuru Peak, formidable ice walls ringed the entire summit and turned back many attempts, but today only small fragments of the great glaciers remain. We paused to watch the sun rise above the horizon and then continued slowly on, each false summit revealing another ridge to climb. At last we arrived at Uhuru Peak. A throng of people in colorful jackets was grouped around the wooden marker at the highest point of the crater rim. The ice does not cover the summit, but ends abruptly 20 or 30 meters below the rim. Uhuru is the highest of a cluster of points, each quite broad and rounded with a precipitous drop on one side into the crater. Actually it is more of a valley than a crater.

As we climbed from Kibo the temperatures dropped from the 30s to the low 20s. Peter said he had never climbed in such warm, calm conditions in all of his 500 ascents. With us he made his 501st climb. Starting as a porter at the age of 13 to pay his school fees, working every other week, he gradually moved up to an assistant guide and is now known as one of the best Kilimanjaro guides. He brought up the tail end of our party. All ten who had started out from Kibo made the summit, though many of us suffered at the altitude. Apathy, nausea, and headaches plagued us; I was quite eager to start down as soon as we arrived at the top. I attempted to photograph the great expanses of rock, ice, and cloud but had difficulty fitting it all in single frames.

I started down as soon as we had finished taking group photos. The descent went much more quickly. I was better able to appreciate the views of the glaciers and crater once rested. The barren boulder-strewn valleys and hills with scattered snow patches made me think of photos I had seen of the Dry Valleys in Antarctica. From Antarctica we dropped down from the rim and picked a path through the tumbled boulders to the scree slope. At that point our guide stepped aside and pointed down. We would go straight, shuffle-stepping through the loose scree for two thousand feet. My altimeter registered a descent rate of more than 9000 feet per hour. So did my stomach, which disagreed with such a rapid rate of descent and sudden physical exertion. The lower slopes just above Kibo were long and drawn out. We were exhausted, thirsty, and still recovering from the altitude. It was hard to believe, as we descended, that we were still far above 17,000 feet, then 16,000, then 15,000, still higher than anything in the 48 States back home.

When we arrived at Kibo at 10am I would have guessed it was late afternoon. It certainly felt like it. After lunch I was feeling much better, having re-hydrated, eaten some food, and rested. The clouds came in late in the morning and it began to snow lightly as we departed for Horombo. A long line of porters and climbers stretched off into the mist. I, eager to get down to more hospitable altitudes and a dry shelter, went on ahead. At times the mist became so thick that I could see no one in front of or behind me. My world was reduced to a foggy circle in the desert, 50 meters across and devoid of everything but scattered boulders. It was a lonely landscape. The miles passed by and I was soon in moorland once again. It was good to see running water and green plants. I met Livia, who was hiking up the trail with GodBless, one of the porters, to congratulate us on our climb. Soon we were once again holed up in our huts at Horombo. After an early dinner we turned in for some much needed sleep.

4 January 2002

After 12 hours of deep sleep I awoke to a spectacular sunrise. Tea was served at 6:30, breakfast at 7:30, and we were on our way by 8:30. The sky was clear but clouds below were fast approaching. They came from both sides of the ridge as we descended into the jungle to Mandara, where we stopped for lunch. Looking back at Kibo, I was struck by how small the mountain looked from our vantage point. Considering that it took us seven hours to climb, one might have expected a more formidable peak. The absence of oxygen must not be underestimated. It felt good to descend, to walk as fast as one wished without concerns of becoming sick, to return to more temperate country. Mike and Hanna were particularly happy, as they had received word the afternoon before that their bags had arrived and were waiting for them at the hotel.

Our last lunch on the mountain was not much different than usual: soup, Tanzanian (French) toast, fruit, fried potatoes, and also baked beans. After the meal all the porters, except six who had been sent down with a sick climber from another party, gathered on the deck of the dining hut to thank us. They even had a watermelon bowl for the fruit salad that had the words "By Bye Our Friend" carved on the outside. They sang to us again, and Peter made a speech of sorts that glorified our success, thanked us, and then dwelled again on our achievement. He was selling his business, but I would rather have heard words about how beautiful the mountain is and how the experience is about seeing the whole landscape (not just the top). Some people push too hard just to bag a summit, on account of talk.

We presented tips, which Andy had collected the night before, and then gave to the porters a bag of clothing and gear John had put together from what we could spare. Peter and the assistant guides organized a raffle of sorts and the donated gear was spread out on a table. My fleece went first, and then shell pants, tops, batteries, a pocketknife, and other items. The looks on their faces were so rewarding. They passed my sunglasses around, trying them on, envious of the one who had chosen them. It made me think about how much we have in America. The man who won my fleece wore it all day even though temperatures were in the 80s. It had become a symbol of status - material goods. It loos as if the whole world is going the way of America.

We continued down to the gate in small groups. For the last quarter mile or so we encountered small children, who rushed out of the jungle or stood beside the trail asking for dollars or sweets. It was difficult to turn them away, but anything I might have given them was packed. There are so many more people like them that I don't know what might be done to help. Having contributed much to the raffle and in a moment of foolishness given away my remaining pair of sunglasses as we were leaving, I had little more to offer. It would be a very bright safari.

We stopped at the Capricorn Hotel to retrieve bags and then continued through Moshi on the road south to Arusha. Outside Moshi a rear tire blew out explosively, but since the bus was a 6-wheel we were able to continue into town and change the tire there. While a few of the porters who rode with us to Arusha were changing the tire, we sat in the hot bus fending off street vendors and wondering about the safety of the men under the bus as it lurched about on the unstable lift. They got the rusted lug nuts off, took off both wheels, rolled the damaged one off down the street, and returned a short time later with another. A bus packed full of locals pulled into a lot. Two goats were pulled out of the cargo hold to the rear; one was taken off down the street and the other transferred to the back of a minibus, which sped off in the direction from whence the goats had first arrived. People of all classes hurried past - businessmen and women, farmers selling produce, and children wandering the streets.

The land looked very sad and barren because of the drought, but the sunset was very beautiful. We skirted Mt. Meru and finally rolled into Arusha around 7pm. We turned onto a dirt side street lined with shacks and shops. It was difficult to believe that a hotel would lie at the end of such a street, but sure enough we arrived at the Ilburo Lodge. We passed no fewer than seven hair salons in the last quarter mile before driving through the gate of the hotel. The grounds were very large, with gardens and banana trees and all sorts of beautiful flowers. The rooms were in pairs in beautiful round thatch-roofed huts; mosquito nets hung over the beds and the decor was distinctly African. The dining room and lobby, in a larger round hut, were quite beautiful as well. We sat at the bar for a drink before dinner, and afterward walked through the gardens. The insect sounds outside were quite loud and dogs barked in the distance. I though it was nice to be back in town, but the dreamy word of the mountain was gone away and the burdens of life had returned.

5 January 2002

Sleep came after we enjoyed dinner and repacked our bags for safari. There were mosquito nets, much appreciated since some insects were flying about. In the morning it was cloudy with light misty rain. The gardens were even more beautiful by day. There were trees of green bananas, hibiscus, roses in full bloom, and countless other colorful flowers including one plant that had thin blade-like stalks with tiny pink flowers along the edges of the blades like ice crystals on the edge of a leaf. We packed up and piled into our safari vehicles - a Land Cruiser and a Toyota minibus. We divided ourselves between the two; I chose the minibus for its larger windows and shaded pop-top. We first went into town to mail postcards, stop at the KLM office, and change money. Arusha is hosting the Rwanda war tribunals and the prisoners are held there, so we were advised not to take photos of field workers or any officials. The city is fascinating, especially the shops lining the side streets. I don't know how some of the shacks can stay in business; so many are in competition with each other selling fruit, meat, sundries, and clothing.

We spent an hour browsing the huge selection of African crafts at the Arusha Cultural Heritage Center and spent great sums of money. I was able to send a short email home saying I'd survived the climb and all was well. After lunch we continued on, driving away from dark clouds to the west that rumbled with thunder. We drove for hours, first on a paved road and then on a very rough dirt road under construction by a Japanese contractor. It was very dusty, dry, and hot. We bounced into the Rift Valley, past Lake Manyara, and then climbed the steep Rift escarpment at the far side of the valley. There, in lush jungle, baboons roamed beside a stream. Our driver, Martin, showed us where elephants had dug in the embankment with their tusks. We arrived unexpectedly at the rim of the Ngorongoro Crater after many miles of winding dirt road in the rain forest. I wonder what will happen when the highway is punched through, opening up those roads to an endless stream of vehicle traffic.

Martin pointed to the crater floor 2000 feet below at two tiny specks that were elephants. Throughout the drive he had been finding miniscule specks on the horizon that were zebras, ostriches, and other animals. We were quite impressed. The sun was low and it set behind clouds as we navigated around the crater rim to the far side. It was very remote and beautiful - the red dusty track could hardly be called a road. In contrast, the lodge was amazing. Two large round buildings adjacent to one another contained the lobby, restaurant, bar, lounge, and hotel shops. Attendants dressed in traditional shukkas hurried to take our bags. Others brought steaming white towels that quickly turned rusty red as we wiped the dust from our faces and hands. Next we were presented with glasses of cold juice and brought to our rooms. From the glass-fronted lobby we could look out through the purple-black reflections in the glass and see the last light of the setting sun. The great bowl of the crater lay below us. A swimming pool shimmered in the light streaming out from the glass walls of the lodge. Our rooms were in round huts strung out along the rim, though "hut" is much too plain a word to describe the accommodations. The rooms were huge, carpeted and lavishly furnished in classic African style. A balcony overlooked the crater. The bath was spotless and the water steaming hot. The lodge was entirely self-sufficient, an island in the jungle.

We washed and then gathered for dinner in the dining hall. Occupying most of one large round building, it was filled with people. The service was comparable to the best of restaurants. The setting was astounding. In the center of the room was a chimney column and stone fireplaces; glass walls looked out on the crater, and beautiful lighting fixtures cast a warm glow under the huge conical roof. At one point during the meal the lights were extinguished and the wait staff came through with torches, dancing and singing and bearing a cake to one of the tables. The food was excellent. After the meal we migrated to the lounge, where we sat on the comfortable couches and sipped drinks and talked until late at night. After the others had drifted off to their rooms, Livia and I sat outside by the pool. One of the guards showed us Cape buffalo just 10 meters away from us, below the retaining wall. The wall ended a short distance away though and the wildlife could come right up to the swimming pool - which the guard indicated by a large pile of elephant dung on the lawn. He said it wasn't safe to walk around but that we could sit for a while.

6 January 2002

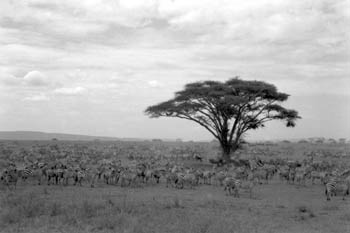

I rose early to watch a beautiful sunrise. The first rays of the sun shone into the crater floor and outlined every ridge beyond with shadows. The sky was mostly clear and the ground wet from light rain during the night. Breakfast was, of course, excellent. Too soon we left the beautiful lodge and departed for the crater floor. The rain had wet the dust and it was quite pleasant to breathe the cool, fresh air as we drove slowly through lush acacia forest and watched many colorful birds flying among the trees. As we moved into grasslands with scattered flat-topped acacia trees we encountered herds of buffalo, a female lion, wildebeest, vultures, gazelles, zebras, hyenas, three cheetahs - the cheetahs were confronted by an angry buffalo that rushed them, stomped, snorted, and paced about before wandering off to graze. We also saw two buffalo banging heads. They conducted themselves in a curiously formal manner, fighting it out to see who was the better.

Ostrich, geese, and many birds small and large walked, flew, and rode on the backs of animals. Bones, mostly of buffalo, were scattered about in surprising numbers - a testimony to the cycle of life. Buffalo were by far the most numerous animal in the crater, numbering in the hundreds. We saw wart hogs with piglets, a black rhino (rhino are nearly extinct and only a few are left in the wild), tawny eagles, crowned cranes, and a watering hole filled with hippopotamuses, pink flamingoes, egrets, and ducks. At the large lake near the center of the crater we saw hundreds of flamingoes and more hippos, as well as many long-legged birds wading about in the shallow water. There were many Thompson and Grant's gazelles, zebras - black and white adults and fuzzy brown and white baby zebras, a large black python beside a stream, and huge herds of gazelles and wildebeest.

Lunch was beside a watering hole where many hippos splashed about. The birds there were very aggressive; the small birds gathered close around us to pick at crumbs and the kites blasted by our faces and snatched food from our hands. We huddled beside the vehicles and tried to watch our backs. Two elephants - probably the same two we had seen the evening before - came to drink at another watering hole. We passed two lions, a male and female, sleeping beside the track, and saw two more elephants, waterbuck, and jackals before we exited up a very steep road out of the crater. It began to rain as we departed and we put down the pop-top and watched the water cascading down the windows. Waves of misty rain drifted across the crater. The windows fogged over and through them we caught glimpses of the very rough, narrow red clay track that dropped precipitously down the slope all the way to the crater floor. It was a relief to be safely at the top.

From the rim we continued on towards the Serengeti. The rain had stopped but the moisture cleared the air and made the hills glow bright green. We could have been in Ireland or Scotland if not for the flat-topped acacia trees and giraffes, zebra, buffalo, and antelope. Maasai villages were scattered along the roadside and we passed many herders, dressed in bright red shukkas, herding cattle and goats. It was very beautiful to see the sun shining through the clouds, making mottled patterns of light and dark across the green hills. We were descending into a huge dry expanse, the eastern Serengeti. Several kilometers farther we stopped at a Maasai village. It was in a shabby state and entirely worked over to cater to tourists, who paid $50 USD per vehicle to watch the villagers sing and dance and peer into the dilapidated mud huts. The primary occupation of the villagers was making beaded trinkets from nylon line and plastic beads, which I found to be rather artificial. I walked around the village but took no photos and hastily sought refuge from the melee back in the minibus.

Continuing on, we soon left the neatly cropped green grass and acacia-studded hills behind. The trees all but disappeared and the dusty track extended to the horizon. We drove at such a speed over the rough road that nothing inside the vehicle could be made to stay still - water bottles migrated across the vehicle and the remains of our boxed lunches opened and scattered their contents on the floor; with duct tape we secured them to a seat but still they nearly escaped. As we drove deeper into the vast expanse of the Serengeti we began to pass boulder piles, weathered domes of granite that protruded above the flat plains of wind-blown volcanic ash that had covered the rock formations below. I would have loved to climb some of them but not only were we passing through, but the rocks were also home to lions and cheetahs a menagerie of smaller animals that would be best not disturbed. We passed herds of waterbuck and gazelle, ostrich, hyenas, dik dik, and then sped onward to see a leopard high in a distant acacia tree. The safari drivers announce the locations of the best animals on their radios, speaking Swahili of course, and we often screeched to a halt, turned around, and sped off without knowing what we would see until we arrived. We were excited to see the leopard because it is quite rare, with only 60 animals in the 28,000 square kilometers of the Serengeti preserve. As dusk fell and we drove into open acacia forest, we encountered a group of monkeys climbing in the trees beside a watering hole.

Camp was set in open acacia forest that lay in the transition zone between thicker forest to the west and the treeless grasslands to the east. Six cabin tents were lined up one beside the other, each with two cots and washstands, with four "choo" (toilet, pronounced "choh") tents and shower tents. Two more tents housed our six staff and a dining tent with an elaborately set table faced a fire pit stacked high with acacia branches. Another fire burned already beside the staff tents; they kept it going continuously to heat water and cook. We were met with hot towels and juice by staff dressed in business suits. It was not exactly what I expected camping in the African bush to be.

Dinner was a multi-course meal served on china, by candlelight, with excellent table service. The staff made a tremendous effort to ensure that our stay was enjoyable. After dessert we sat beside the fire, our chairs making a semicircle in the firelight. People drifted off in twos and threes until just a few remained. Once the fire had died we were advised to go to our tents. The Serengeti was quiet, except for insect sounds and once in a while a grumbling lion in the distance.

7 January 2002

We rose before sunrise for tea and embarked on a five-hour game drive. The sunrise, behind silhouetted acacia trees, was spectacular. Martin spotted a cheetah eating a young gazelle in the shade of an acacia - he had noticed an agitated adult pacing and watching the tree where the cheetah rested. As the sun rose and the heat increased we encountered more gazelles, eland, waterbuck, impala, giraffe, buffalo, hippopotamus, ostrich, rock hyrax, zebra, wildebeest, and many birds. We found another cheetah perched on a boulder pile surveying the country and looking for prey, and later, an adult cheetah teaching two young to hunt. They were playing with a baby gazelle, and we watched through binoculars as they batted it about and chased it down again and again. We passed a kill surrounded by vultures and hyenas, saw more monkeys in the trees, and finally on the way back spotted three lionesses resting in the shade of a small tree. Agreeing that it was wise to rest through the heat of the day, like the animals do, we happily ate brunch and stretched out in the shade to read and relax.

At 3:30 we departed and drove in the opposite direction, into the forested hills. We saw herds of giraffe, zebra, and elephant. An endless stream of baboons of all sizes filed out of the grass and across the road, the youngest clinging to the bellies of adults. The monkeys were adorable, pummeling each other and rolling and tumbling about and scampering up and down trees. At a hippo hole we saw many more animals splashing and snorting in the brown water. It is difficult to imagine that such a large animal comes onto dry land at night to feed, and that it can run quite rapidly. We walked along the riverbank watching the hippos and looking for crocodiles. Only there were we able to get out of the vehicles and walk, and it was a welcome chance to stretch especially after we had spent a week hiking on the mountain every day.

The drive back to camp was beautiful. The sun was low and it illuminated the trees, hills, and clouds with a golden glow. We watched giraffes ambling among the trees, passed the herd of elephants again, and saw waterbuck, gazelles, a mongoose, impala, buffalo, and zebra. Behind us trailed a wispy cloud of dust. It was all so surreal. The sun slipped below the horizon in a blaze of orange and red, setting the towering clouds to the west ablaze. The rest of the sky was clear and it was very calm and serene. Livia and I stood looking out the back of the minibus as it bounced along the dusty track. Opus, Erin, and Hanna sat in front of us, looking out at the sunset and snapping photos. The wind whipped past, and we watched the colors of the sunset glow brighter and brighter. Darkness fell as we arrived at camp.

I ordered up a hot shower, which was brought in a 5-gallon bucket from the fire and hoisted above the shower tent by means of a rope and pulley. Dinner by candlelight was both tasty and very enjoyable. We finished the meal with tea and then sat around the fire, drinking good African beer and talking. Martin told us about how he met his wife and the elaborate customs of choosing a suitable wife - based on her family, her background, where she lived, her tribe, and a host of other criteria. It was interesting to hear. After a time I retreated to the tent to put my things in order and escape from the wood smoke. Wood fires were used for everything in camp; even the wash water that came every morning smelled vaguely smoky. But somehow the staff managed to cook exquisite meals on beds of coals.

The stars were so bright in the clear sky. Livia and I took our pillows a short distance from camp, away from the kerosene lanterns that sat in front of every tent, and watched falling stars. Outside camp we heard more large animal sounds, lions we later learned, but none appeared to be stalking us as we gazed innocently skyward. I will always remember the stars, glowing tents, distant campfire and murmuring voices, chirping crickets, and silhouetted acacia trees.

8 January 2002

We departed after breakfast for another day of game drives. Our lion tally quickly grew to twenty animals and our wildebeest count jumped into the thousands. Not far from camp, at a place that on previous days had been an empty grassy expanse, wildebeest and zebra stretched to the horizon. They were migrating across the Serengeti and we happened to be parked in the middle of them. Standing on the roof of the minibus, I looked out over the dusty, churning masses of animals. Flies buzzed around us in annoying quantities. Some animals grazed and clusters of wildebeest rested in the shade of acacia trees, while others hurried past in an endless stream. Off to the side we saw a large male lion. Nearby zebras were interested but did not seem overly concerned; they must have known that the lion was not hunting. We thought it was interesting that game did not take flight at the sight of the big cats - I suppose they must know that there is nowhere to hide.

We moved on to a small water hole where 15 lions - females and young males - had congregated. A line of wildebeest marched past on the opposite side of the track. A 16th lion approached and was warmly greeted by a cub, which seized the tail of the adult in its mouth and followed behind. Two young males were locked in a standoff over the remains of a young gazelle. Neither was willing to concede the carcass and they were evenly matched, so both lay growling in a heap that occasionally tumbled to a new position. Next we encountered a huge herd of zebra that had moved in and was blocking the way quite effectively. There was a lion in the underbrush beside the water hole where the zebras were drinking in successive waves, and they repeatedly ran away splashing and making loud distressed noises that sounded much like donkeys. A little farther, three large male lions rested beneath an acacia tree.

Lunch was at the top of a small rise to the south, where tables shaded by thatched umbrellas were clustered among acacia trees. Numerous bright blue birds fluttered about in search of food. The meal, brought in a basket from camp, was very good - pasta and green salads, fried chicken, fresh bread. We were on our way soon to escape from the flies that had just that day appeared in the Serengeti, probably with the herds. We drove around the more remote southern reaches of the park where the animals were fewer and more skittish. At a large water hole we saw many flamingoes. Another lion lay asleep on her back with all four paws in the air beside the track, apparently unbothered by our presence just 5 meters away. Martin spotted another leopard, the second of the trip, as it leapt into an acacia tree. We passed more elephants and then, just 200 meters outside camp, two more lions. Martin said we had been extremely lucky and that he had never seen so many cats and so much wildlife on one trip. The weather was also very favorable, both on the climb and on safari.

Our last night in the bush was spent much like the others, good food followed by tea and a couple hours chatting beside the campfire. We were all tired from the long day and turned in early. Once again I heard lions in the night before I fell asleep.

9 January 2002

The drive out of the Serengeti seemed much shorter than the drive in. We stopped for an hour at Olduvai Gorge to look through the museum and listen to a brief history lecture. Descending the rough and dusty road to Lake Manyara, we drove into lush jungle where baboons and monkeys played, herds of elephants roamed about, and lions climbed trees to seek cooler perches. There were many young elephants and our vehicles were charged several times by huge adults when we lingered too long. It was rather intimidating to be 10 meters from an angry animal much larger than the minibus. However, the charges amounted to no more than flared ears, short rushes, snorts, and stomping. Most of the elephants calmly ambled along and tore down tree branches for food. It was impressive to see how destructive the elephants could be - some trees were completely shattered. The tree-climbing lions were the same species of cat we had been seeing in the Serengeti, but in Manyara they sleep on the broad branches of the flat-topped acacia trees. Next we saw black giraffes, buffalo, baboons, and adorable families of monkeys. After a stop at the lake (which is very shallow with expansive mud flats) we returned to the top of the rift via the steep, dusty road and checked into the very beautiful Manyara Lodge.

The remainder of the afternoon we spent at the pool, right at the edge of the rift escarpment so that from the water's edge we could look down into the valley, over Lake Manyara, to the hazy hills beyond. There was a bar beside the pool and some of our party enjoyed this very much. Later, after the rainbows to the east had faded and the sun had set in low clouds, we dressed for the evening and returned to the bar. Dinner was quite good; we ate on a balcony and looked out at the twinkling lights across the valley and the stars overhead. It was a beautiful place to spend our last night in Tanzania. Most of the others, particularly those who had imbibed a bit excessively, returned to their rooms. We sat by the pool, looking up at the stars in the warm night. They were not as bright as they had been at Horombo, or even in the Serengeti, but were beautiful nonetheless. I could have counted all the electric lights in the huge expanse below on my fingers, there were so few. It was yet another reminder of how empty and wild Africa is.

10 January 2002

Rising early at 6am, several of us watched the sun rise over the rift valley. The temperature was so pleasant - just as it had been the night before. The air was so comfortable and fresh. From our perch on the rift escarpment we watched the sunrise colors reflected in the surface of Lake Manyara. The stars and the crescent moon, which had been full when we were climbing the mountain, faded from sight as the sky brightened. Those nights on the mountain seemed so far away that weeks could have passed. Birds were singing as we ate breakfast. We packed up and traveled down the steep and dusty road to the valley floor one last time, passing on the way cattle herders driving their animals all the way from Lake Victoria to markets in Arusha. In the opposite direction, people carried bundles or pushed heavily loaded bicycles destined for markets above. Fruit, chickens, and bundles of grass were among the goods traveling the road that morning. In the village at the base of the escarpment we passed through the market, with its shabby dust-covered booths selling colorful fruits and textiles. One booth had huge hanging bunches of bananas in every color - red, yellow, brown, green, and gold. The fruit sellers always have the most colorful shops - though every structure is the same uniform red color from the dust.

Once again, on the return the drive seemed shorter. We were served lunch at Mr. Jordan's house in Arusha, then transferred our belongings to a bus and went to the Ilburo Lodge to retrieve more bags. There we left Livia, who would catch an evening flight to Germany. The rest of us took the TSA bus to the border, switched to two Kimbla minibuses, and arrived in Nairobi at 6:30 in the evening. While still hectic, the border crossing seemed to go more smoothly. If I travel through Africa again I will be sure to pack extra items to trade; at the border one could acquire a valuable woodcarving for a very inexpensive Western souvenir. This time though I chose not to accumulate any more African artifacts. It was dusty and hot - more than 100 degrees in the shade, and I had little water and no money to buy more with. I had dispensed of all but $20 USD for a possible departure tax, mostly on tips and food and transportation.

We once again passed Maasai herders and brick makers and sellers of produce, but what impressed me most were the rock crushers. At gravel pits people sat cross-legged beside waist-high piles of crushed stone of the sort that might be used in concrete, breaking larger rocks with hammers and tossing the pieces one handful at a time onto the slowly growing pile. They must be poor indeed if it is economical for them to spend so much time crushing rocks.

11 January 2002

We took a taxi from the Mayfair to the Nairobi city market after breakfast. The market was fascinating to see but stressful to experience. Fruits and vegetables and other foodstuffs could be found, but by far the most numerous goods were woodcarvings and pottery and textiles and crafts directed at foreign visitors. The vendors were very aggressive and together formed a net designed to lure customers into parting with their money. I had by that time become reasonably adept at bartering, having paid too much previously for a few items after accepting too high, but I had very little money to spend. Even so, the shopkeepers were asking to trade the shoes off our feet and the shirts off our backs. I kept mine, and went about offering $2 USD for overpriced goods. Many of them were less costly farther south, out of the city, but some were just the opposite. It was obvious that the people in Nairobi weren't at all excited about things such as ballpoint pens though, unlike the remote villages. I managed to acquire a red shukka cloth for just a tiny bit over its wholesale price - I bought from two reasonable shopkeepers and it was somewhat comical to see the looks on their faces when they heard what I was asking to pay. They looked as if they were being forced to sell to me. I nearly felt bad about it, but the Nairobi businessmen do comparably well so there was little cause for worry. I avoided business with the shadier vendors - we were often the 'first customers of the day' and so would get a good price. Many shop owners claimed to be the artisans, including the art seller whose paintings all had different signatures on them. At length we regrouped outside the market and explored the main street.

Small children occasionally came up to us asking for alms. One of the supervisors or officials at the city market told us that we should buy them fruit, for if we gave them money they would buy gum or sniff glue. Indeed, the next shuffling 10 year old wearing tattered, soiled clothing clutched a nearly empty plastic vial. It was disheartening. Also disturbing were the children we passed in the hills near Ngorongoro, who stood in front of a school motioning for pens and paper, or held up an envelope asking for more. I wish I had something to give them. The African people have so little and we have so much that the contrast was sometimes painful. Nearly every Maasai child we passed whistled, waved, or called for a ride or a handout.

We drove past the Kenyan Parliament buildings on our way back to the hotel. The yellow brick buildings were not particularly attractive but neatly kept. The architecture throughout the city is quite varied, with many of the buildings appearing to date from the 1950s and 1960s. The roads are sound but chaotic. There is no abundance of dents and dings so the streets must be relatively safe or the drivers skillful, despite appearances. The police exercise tight controls on licensing, insurance, and driving while intoxicated; we passed many roadblocks while traveling to and from Arusha. We tourists are allowed to pass without stopping and the officials are not supposed to bother us, but from that one can infer that the officials may harass the citizens as much as they like. Security elsewhere seemed quite high, but at least we could feel safe. Guards were numerous in our hotel. At banks and change bureaus armed guards and doormen were common.

We became mired in unusually heavy traffic en route to the Carnivore restaurant for dinner. It was unmistakably a tourist trap; I am not sure if the restaurant is popular among visitors because it has good, exotic food, or because tour operators are encouraging us to spend more money in the local economy. It was interesting to try cuts of zebra and ostrich, both of which were much like beef, and crocodile, which was fishy but bony and generally not a fine meat. Also on the menu were beef, mutton, chicken, pork, bread, soup, salads, and desserts. As we ate, the room filled with smoke from the circular barbecue pit at the center of the large restaurant. The decor was much like what one would expect in an American steak house. Chunks of meat were skewered on short Maasai-style wide-bladed spears and cooked over the barbecue, and wait staff came by with these spears and sliced off meat onto our plates until we had eaten enough.

When we arrived at the airport to catch the 11pm British Airways flight to Heathrow, we discovered that the computers were down and that BA was checking in the full 747 manually. Kimbla Safari had confirmed our tickets while we were away, so we were able to bypass much of the line and check in. The plane took off two hours late. Security at the airport was loose. On entering, all bags were X-rayed but one could easily have bypassed the machine. Green "security screened" stickers were affixed to our bags but these soon fell apart and became scattered all over the terminal.

12 January 2002

We landed in darkness at Heathrow, after being further delayed in a holding pattern by mist and the usual Heathrow delays. I was seated in row 25 and had commandeered an aisle seat instead of mid-center section during the confusion of checking in and seating everyone. It was good to be forward, because I was early off the plane and was near the front of the lines at immigration in London. I retrieved my checked bag, took the train to Terminal 3, and checked in for my flight to Newark still with time to spare. I walked around the terminal exploring the shops and admired a $6000 USD bottle of wine and even more expensive diamonds. The wealth was in such contrast to what I'd seen in Africa. The flight to Newark was long and uneventful. I slept a little, read a lot, and waited eagerly for my arrival back in the States.

Watching animals in the Serengeti, staying in cushy lodges and camps and passing time with friendly and interesting people half a world away from home was the best thing I ever did with a college winter break. I'm sure going back would be totally different; this time the weather was so perfect and the animals so abundant and it was one of my first international trips.